Determining Powder Charges

other By: Steve Garbe | December, 25

One of the commonly asked questions from new black powder shooters is: “How do I determine the amount of black powder to load in my cartridges?” Hand in hand with this question is the explanation that because of heavier modern brass, cartridge designation such as .45-70 or .50-90 does not mean a powder charge of 70 or 90 grains. Modern smokeless shooters, used to specific recommended charges in a given caliber, are confused by the way that black powder, being a bulk propellant, is loaded without strict attention being paid to weight. Hopefully we can shed a little light on this somewhat confusing topic for new shooters.

Adding to the general confusion of powder charges in a given black powder cartridge is the myriad of chamber reamers with their different leades and throats. Obviously, some of these chambers will allow for different seating of bullets (overall cartridge length) and the bullet’s designs with their varying dimensions will change the OAL of cartridges in a specific rifle. Therefore, establishing an overall cartridge length using a specific bullet in your particular rifle is critical.

Generally speaking, there will be two types of ammunition for your new black powder single shot; hunting and target. Hunting ammunition has different requirements than target ammo, the main difference being that hunting cartridges need to be sufficiently accurate while also being able to withstand the rigors of field use. Target ammunition, on the other hand, is focused almost completely on the best possible accuracy, as it can be transported to the range in covered boxes and be “babysat” until it is used.

Hunting ammunition should be able to be chambered and extracted without difficulty. This means that the bullet needs to be seated off the lands/leade so that there is little or no engraving of the lands on the bullet’s forward driving band. Also, in the case of grease groove bullets, it is desirable that all the lubricated grooves are covered by the cartridge case mouth, in order to keep dirt from accumulating. Paper patched bullets should be seated with enough friction that they can tolerate the repeated handling that occurs in the field.

Match ammunition generally shows best results when the bullet is seated out far enough that the first driving band of the bullet is engraved half its width by the rifling. The cartridge must be able to be seated by closing the action; the loaded cartridge should not have to be seated in the chamber by other mechanical means such as prying or tapping. For safety considerations, one should be able to remove the loaded cartridge without resorting to a cleaning rod to eject the cartridge from the chamber.

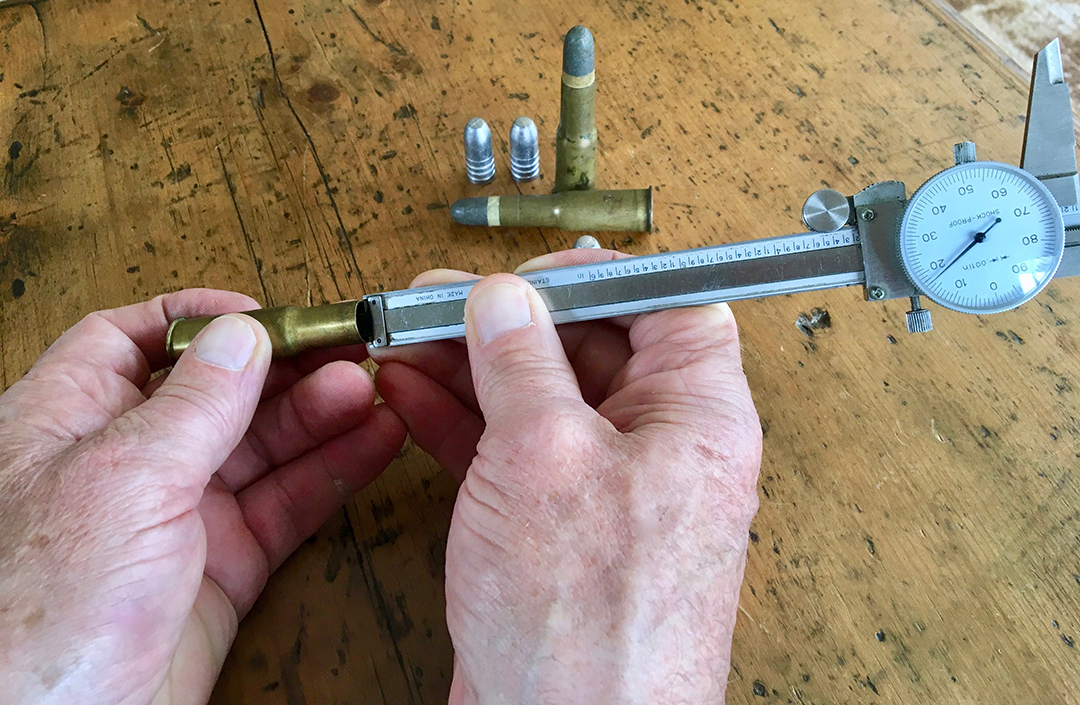

Let’s determine optimal overall cartridge length. With an unprimed and uncharged case, seat a bullet in the case mouth at an obviously “too long” overall length. Gently push the cartridge case into the chamber until it stops and measure the distance from the cartridge rim to the back of the barrel. This measurement gives you a rough idea of how much further to seat the bullet in the case. Take note of how much the driving bands of the bullet are engraved by the rifling. This rough measurement can be altered to give best overall length. Seat the bullet in the test cartridge until a specific overall length is reached with the desired amount of rifling engraving on the bullet driving bands.

Once you have established the maximum overall length for a specific bullet/cartridge combination, then the proper powder charge can be calculated. Bulk measure the powder to an approximation of amount and drop-tube this into the case. Seat the wad on the powder and then measure from the case mouth to the wad for depth. Then, using the dial caliper, measure the depth of seating on the bullet. A bit of trial and error is needed here but the proper charge is soon determined. I usually add .050 to the seating depth measurement to allow for a slight compression of the powder.