Hanna's .41 and .45 Colts

From Reloader's Press

other By: Dave Scovill | June, 25

On the drive home from our Kansas deer hunt this year, Roberta and I stopped to visit Charles Hanna and his wife, Phyllis, in Augusta, Kansas. Roberta and Hanna became great friends several years ago at the annual

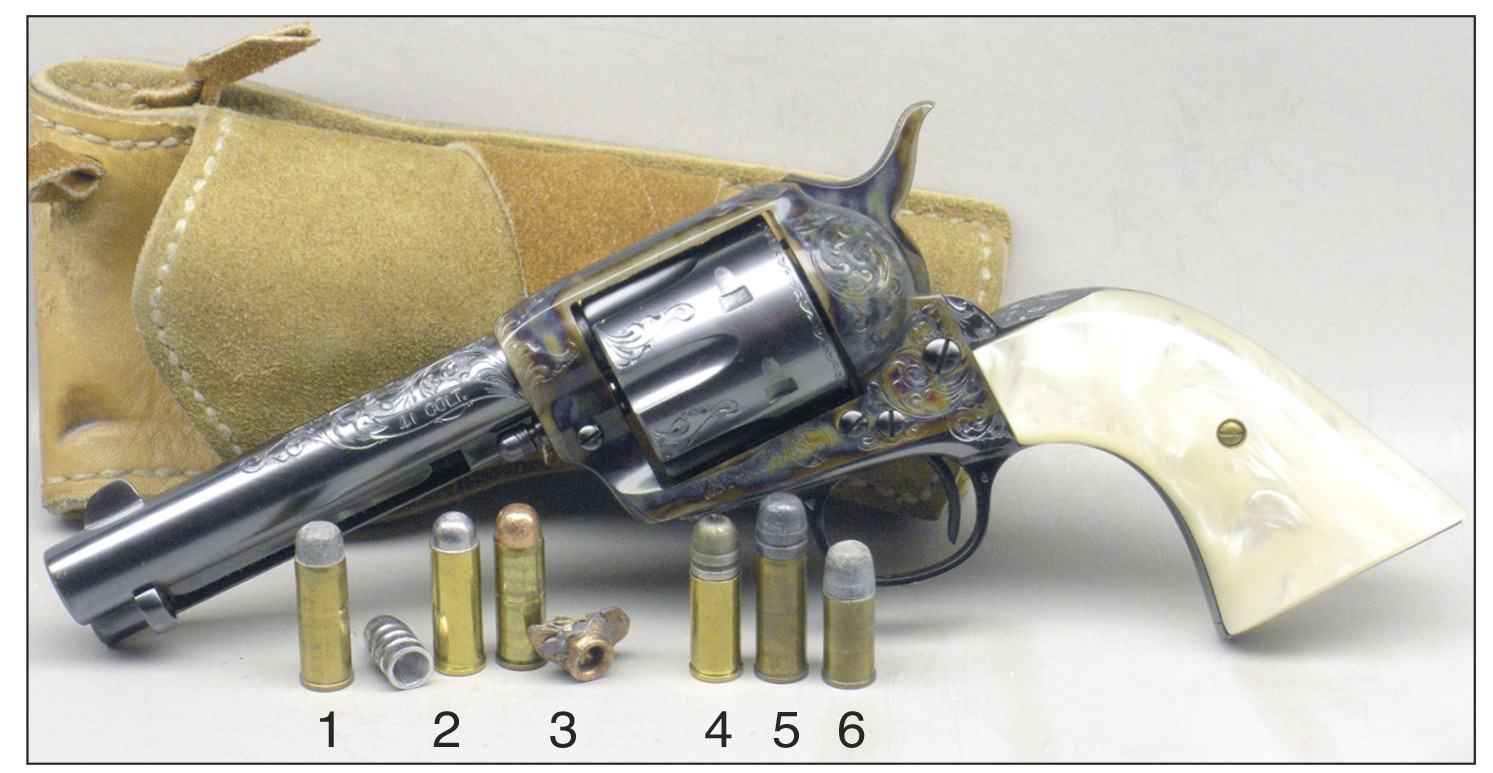

This year, Charles and Phyllis treated us to a fresh pot of coffee and cookies while there were four single-action revolvers lying at the center of the table. Two were Ruger Blackhawk .44 Magnums; the other two were Colts. Hanna noticed Roberta eyeing the two Colts with 4.75-inch barrels in front of her, and at his invitation she picked one up.

Mulling over our visit at the Hanna household during the two day drive home from Kansas, I found Hanna’s choice of handguns interesting, mostly because he could have chosen almost any handgun as a backup to whatever the state of Kansas might have foisted on him. Who would have guessed an almost ancient Colt SAA .45 would be lurking in the door pocket of an otherwise modern police cruiser? I almost had to laugh, since it was pretty much a duplicate of the sixgun that has ridden with Roberta and me for upwards of 25 years over thousands of highway miles across the lower 48.

My choice of sixgun and cartridge was almost the opposite of why Hanna came to the same conclusion. By that I mean, he is an avid researcher who has summarized a number of references that document the use of the .45 Colt. Several of those events were chronicled in Elmer Keith’s Sixguns, where some would-be tough guy decided to challenge a lawman armed with a .45. There was also Keith’s rodeo – hanging from the stirrup of a runaway bronc that would have killed him had it not been for a bullet to the horse’s head from a Colt SAA loaded with a 250-grain flatnose, conical lead .45 Colt slug backed with 40 grains of black powder.

Eventually, Keith swore off the .45 Colt when a load using a case full of black powder under a 300-grain .45-90 bullet blew the loading gate off. Thereafter, he experimented with the .38 and .44 WCFs and .44 S&W Special, until the latter was generally perfected with his Lyman 429421 semiwadcutter seated over a healthy dose of the then-new Hercules 2400. In later years, however, Keith lamented that if limited to factory loads in any sixgun cartridge, he would choose the .45 Colt –mostly, it would appear, because he deemed factory .44 Special loads as historically anemic. Keith also noted that he favored the .41 Colt over the .38 S&W and S&W Specials with the somewhat popular 200-grain Police loads.

So with some measure of reluctance, I sold my prized S&W Second Model .44 Hand Ejector Target and Colt SAA .44 Specials, and the next few years were consumed by a first generation Colt SAA that was shipped to El Paso, Texas, as a .41 Colt in 1908, and sometime later was converted it to .38 S&W Special. It turned up in a pawn shop in 1970 for the princely sum of $125.00, and I converted it to .45 Colt with a new cylinder and 7.5-inch barrel from Numrich Arms.

The trials and tribulations with the .45 Colt in that SAA have been summarized in these pages and two books previously, so I won’t go through all the details, but in time, with a properly designed bullet cast from the correct alloy and sized accordingly, the .45 Colt has proven to be capable of fine accuracy at appropriate velocities. Along the way, with the help of folks at RCBS, including Art Peters and the late Bill Keyes, we have the proper reloading dies, including cowboy dies intended for use with cast bullets, and my 45-270-SAA cast bullet design can be pushed to 950 fps or so from a 7.5-inch barrel without busting the seams. (Add 300 fps to that in an old or New Model large, .44 Magnum- frame size Ruger Blackhawk .45 Colt.) Currently, the only problem is the oversized chamber throats, .456 to .457 inch, that are typical of Colt SAAs, while just about every other outfit has conceded to proper .451- to .452-inch throats. The oversized chamber throats can be dealt with by using the proper cast bullet alloy (one in 16 or one in 10, tin/lead, and/or Lyman No. 2) that bumps up to form a gas seal with an appropriate powder charge. No doubt, coordinating all these factors in their proper place, the .45 Colt can still be a challenge to the casual handloader. Taken one step at a time, however, it all comes together quite easily, although it may not be the first choice for the highballing reloader who just wants to work on the edge of magnum pressures with recipes that can be slapped together with little or no forethought.

Of course, Keith was using the post-1880 UMC (Remington/UMC in 1912) load stuffed with 40 grains of black powder under a 250-grain bullet that developed a full 900 fps, not the issue military load with 28 grains of black under a 230-grain bullet, aka .45 Colt Government or .45 S&W, which are one in the same. It is also interesting to note that for all the historical interest in Keith’s remarks in Sixguns regarding the .44 S&W Special, it is extremely rare for folks to show much interest in Keith’s remarks about the above 40-grain, black-powder load with the 250-grain flatnose, conical- shape bullet in the .45 Colt he used to dispatch wild cattle and rank horses. If you toss out the black powder, it is still rare for folks to note that Keith was also a big fan of the smokeless loads that effectively duplicated the black-powder load. Keith also mentioned several times over the years that the old 250- to 255-grain flatnose, conical lead bullet gave the best penetration on wild cattle and game. It is also fairly easy, apparently, to miss Keith’s comments about that blunt 200-grain .41 Colt slug.

Twenty-six years on this job has suggested the oversight regarding Keith’s endorsement of the .41 and .45 Colt black-powder loads with those 200- and 250-grain lead alloy bullets, respectively, is the result of selective reading; folks simply single out the .44 S&W Special or some other subject of interest, ignoring all the other information that is available about subjects of lesser or no interest. Of course, that’s just politics, singling out stuff you might be interested in and agree with . . . ignoring all else. As my mother would quietly point out with characteristic insight at the dinner table: “That’s a good way to stay stupid.”