Learning to Load

.45-110 Sharps the Old Way

feature By: Harvey Pennington | August, 20

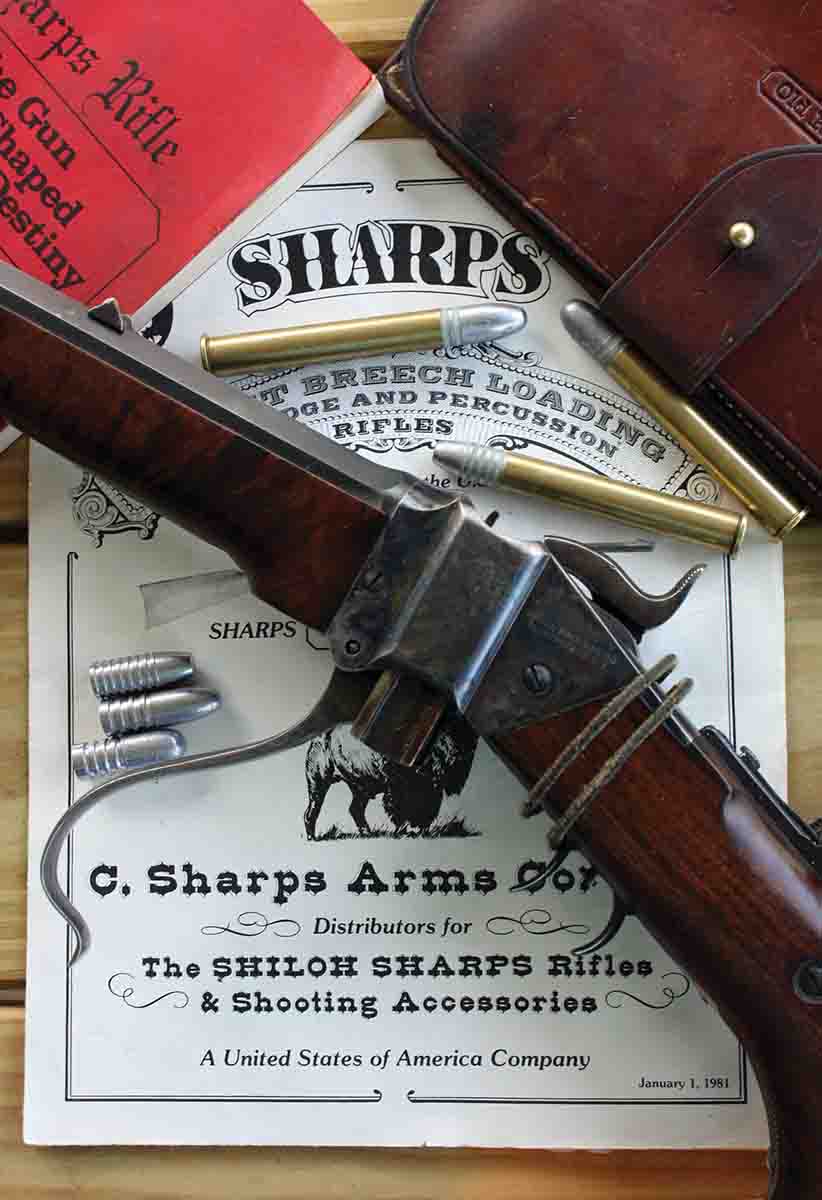

Back in early 1982, I was more than a little excited when my new Shiloh Sharps Model 1874 rifle arrived. It had been manufactured by the “Shiloh Rifle Mfg. Co., Farmingdale, N.Y.” and bore the “Old Reliable” stamp on its barrel. Just as I had ordered, my new rifle was their No. 1 Deluxe Sporter Model, with a 30-inch octagon barrel, weighing 10½ pounds, and was chambered for the .45-110 27⁄8-inch cartridge. I had purchased the rifle for hunting – as I had specified – and it came fitted with the basic Shiloh sporting tang sight and blade front sight.

Some years before, my interest in such a rifle had been piqued by an Elmer Keith article. Keith had described the long-range accuracy and effectiveness of the 1874 Sharps rifles with its heavy black-powder loads and cast bullets. By that time, I had begun hunting almost exclusively with smokeless powder and cast bullet loads in older calibers. Hunting with the larger Sharps cartridges loaded with cast bullets and black powder, seemed to me a logical extension of that interest. So, once I learned of the new Shiloh reproductions, it was just a matter of time until I placed an order for one.

As you can imagine, my first thought upon receiving the rifle was to shoot it. I was eager to test its accuracy with black-powder loads and some heavy bullets. But I was about to be disappointed.

Now, remember – this was early 1982, and there was little contemporary information concerning the correct way to load those old, large black-powder cartridges. For instance, publication of the classic “SPG Lubricants BP Cartridge Reloading Primer,” by Steve Garbe and Mike Venturino was still about 10 years away, as was Paul A. Matthews’ book, “Loading the Black Powder Rifle Cartridge.” Later, I learned that many other shooters in the early 1980s, who were inexperienced with loading black-powder cartridges were having the same problem that was about to perplex me.

Anyhow, I loaded some .45-110 cases with a large rifle primer, poured in about 100 grains of 2Fg DuPont powder and seated a Lyman 457125 bullet directly on top of the powder. I had lubed the bullet with a popular commercial bullet lube that had proven very satisfactory for me with my smokeless powder, cast bullet loads. I then tacked up a target about 50 yards away, seated myself at my shooting bench, loaded one of the big cartridges into the chamber of my new rifle, set the trigger and touched it off. When the expected, yet pleasing, cloud of smoke cleared enough, I could see that the bullet had landed fairly close to center on the target. Then, I loaded a second cartridge and fired. That second bullet barely landed on the target, had keyholed and passed through the target completely sideways. I was puzzled, to say the least.

I carefully cleaned the black-powder residue out of my barrel and took a good look through the bore. All seemed just fine; the bore was smooth and shiny. There was no sign at all of any damage to the bore or the muzzle that could have caused the bullet to keyhole.

I tried again, but the inaccuracy of my loads at only 50 yards was startling. Although I don’t recall another bullet passing through the target totally sideways, almost all (except for the first shot through the clean barrel) showed obvious signs of tipping.

So, what had I done wrong? It was obvious, since there was nothing wrong with my rifle, that the fault had to lie with the loads I had prepared, and the problems caused by the black-powder residue left in the barrel after that first shot. Now, it stood to reason that the old-time buffalo hunters had not stopped to clean the bores of their rifles after each shot; there had to be something more to loading those cartridges that I needed to learn.

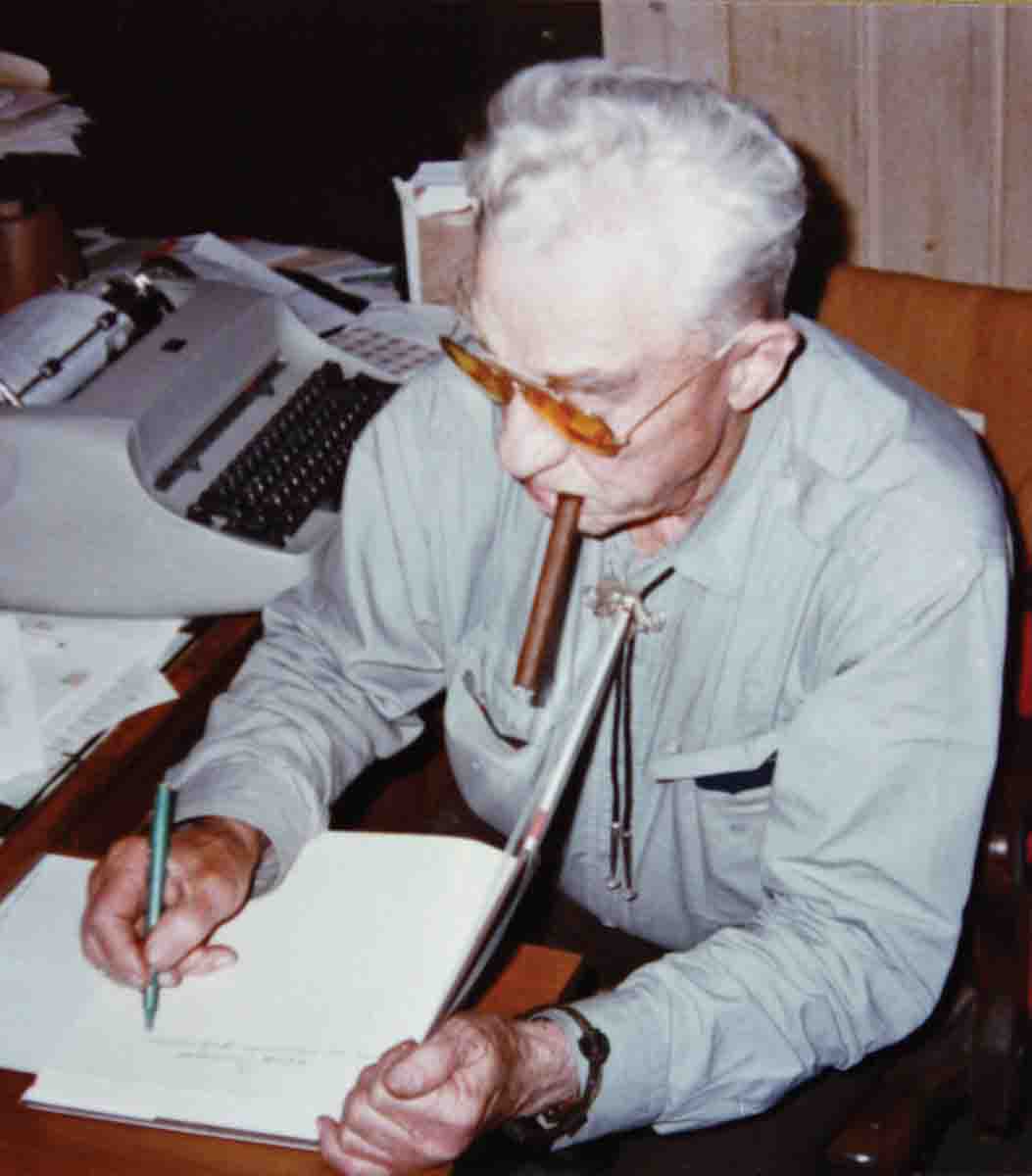

Before proceeding, I decided to seek the advice of an expert – Elmer Keith. Sadly, when I phoned his house, Mrs. Keith answered and told me that he had recently suffered a stroke and was, as I remember, in a nursing home in Boise at the time. That came as shocking news to me. I had previously visited Elmer three times at his home in Salmon, Idaho; also, I had written and received a few letters from him, and had talked to him a few times on the phone. He was always very helpful, congenial and welcoming. I knew that, along with the thousands of other fans of his many articles and books, we would all share a common feeling of great sadness and loss.

As for the keyholing problem I had experienced, I still decided to seek his help, but this time through his writing. I remembered his old article that had, years before, fueled my desire for a Sharps rifle; I thought there was a chance that it might provide a clue that would help. It took a while, but I finally located the article in a 1974 edition of a magazine entitled Complete Guide to Blackpowder, which was published by Guns & Ammo. His article was titled “The Magnificent Sharps Rifle…as Seen, Shot and Remembered by Elmer Keith,” and it was filled with information about the history of the various Sharps rifles. It also contained some information that would prove quite helpful in solving the problem I had experienced.

In one paragraph of his article, Keith mentioned an 18-pound, .45-100 Sharps rifle he owned, which had originally belonged to Hank Waters. Waters had used the rifle during the hide-hunting years and according to Elmer, the rifle’s bore was still in perfect condition. In that article, Elmer wrote about the loads he had prepared for Waters’ Sharps to be used at a turkey match at Challis, Idaho. Here is the part that caught my eye: “…The old Sharps ate out the center of the 10-ring each shot on that cold, windy day. I had it loaded with 566-grain flat-base, paper patched bullets. On top of 100 grains of Fg blackpowder, I loaded a very thick heavy card wad, then a 1⁄4-inch wad of elk tallow, and then the paper-patched bullet.”

Further, in the same article, Keith (who was born in 1899) also mentioned that as a boy, he had become acquainted with some of the original buffalo hunters. It was obvious that Keith would have learned from them the way they loaded the old black-powder cartridges. Now, I wasn’t using a paper-patched bullet, but it made sense to me that the tallow must have been the key to softening the fouling – whether the bullet used was patched or grooved. So, I decided to try it his way. Besides, I’ve always thought that the more a hunter/shooter puts into preparing his loads, the more satisfying it is when things finally come together.

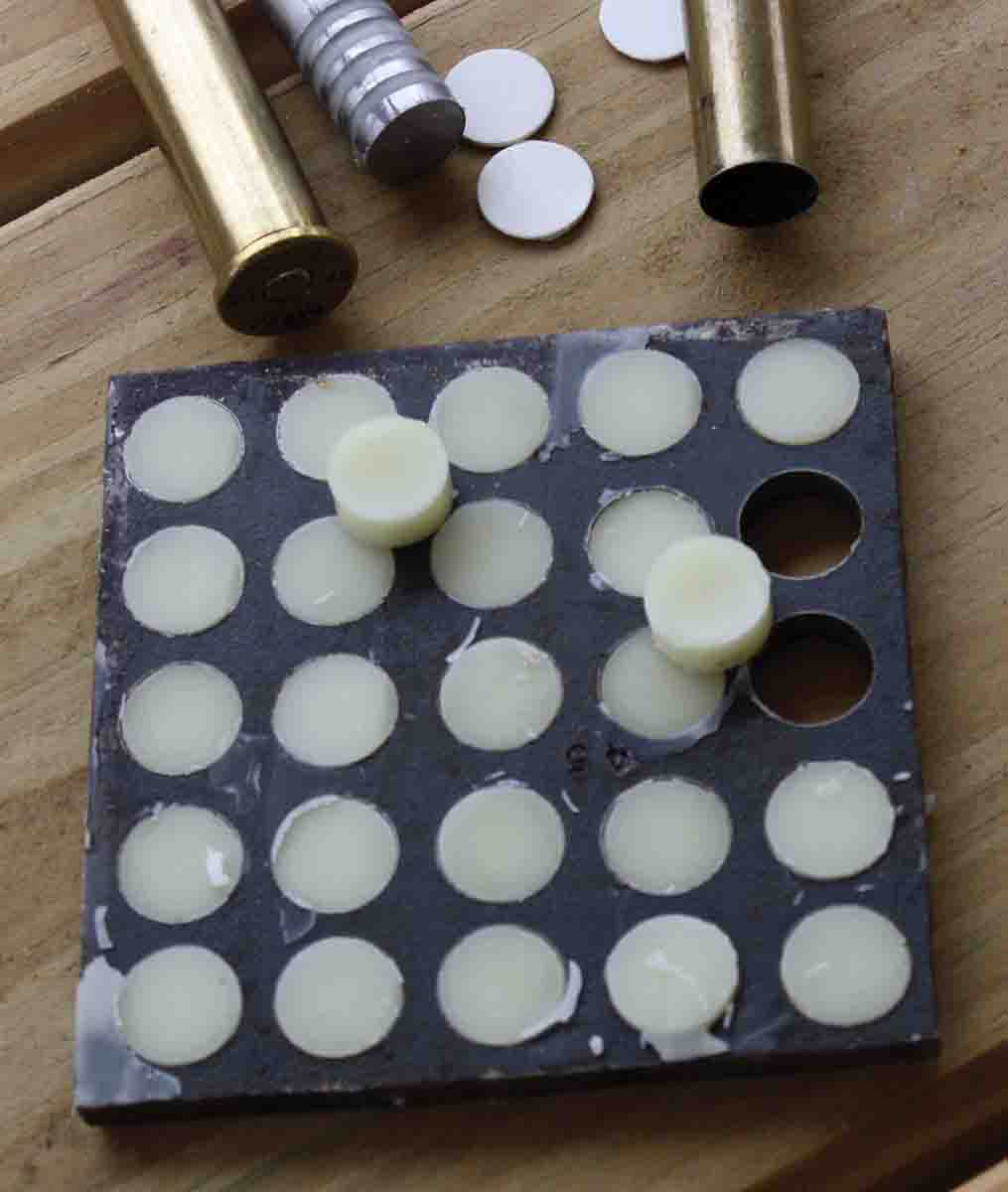

I didn’t have any elk tallow at home, of course, so I went to the meat-cutting section of a local grocery and got some beef fat. When I got home, I rendered the tallow from the beef fat on our kitchen stove. For those who may not have done this, the beef fat was placed in a pot, and then warmed on low heat for a couple of hours until the tallow had slowly melted and separated from the meat; the melted tallow (now a liquid) was separated from the remaining beef by pouring it slowly from the pot through a strainer and into a separate container where it was allowed to cool and solidify. It was then ready to use.

For my next loads in the Sharps, I used 84 grains of Fg DuPont black powder. That amount seemed about right to allow room for the card wad, tallow and bullet that I would be inserting. The card wad was punched from an orange juice carton, and a dowel was used to firmly seat it on top of the powder charge. Next came the beef tallow; it was very soft, but, as nearly as I could, I put a 3⁄8-inch wad of tallow on top of the card wad. Next, the Lyman 457125 bullet (1:16 alloy) was seated so that the overall length of the cartridge was 3.630 inches. I also smeared some tallow into the grooves of the bullet before seating it.

My next shooting session with the new Sharps was much more satisfying than the first had been. With the target at 100 yards this time, three shots were fired without cleaning the bore. All bullets hit the target point-on, and the group was about three inches; the tallow had done its job of softening the fouling left by the residue of the previous shots. I was beginning to learn.

However, there was more to do. Although the beef tallow seemed to be doing its job, it was extremely soft, messy and difficult to use. It was slightly thinner than the consistency of Crisco. Then, in the spring of 1983, on one of my family’s trips to Montana, I went by the Shiloh Arms building in Big Timber and was looking at some books they had for sale. One was “Schuetzen Rifles-History and Loadings,” by Gerald O. Kelver. It had been copyrighted in 1972 and it had a section that listed various old-time formulas for bullet lubes. The ones that caught my eye were those using a combination of tallow and beeswax. The ratios given ranged from one part beeswax to four parts tallow, all the way to four parts beeswax to one part tallow.

Another book I found there that proved extremely helpful was “Sharps Rifle…The Gun That Shaped American Destiny,” by Martin Rywell. It actually contained a reprint of the Sharps Rifle Company’s instructions for reloading metallic shells. Their recommendation for loading unpatched grooved bullets was to use a pasteboard wad on top of the powder charge and insert a 3⁄16-inch lubricant disc composed of one part beeswax to two parts sperm oil in weight. They also instructed that the grooves of the bullet be filled with the same lubricant.

So, beeswax seemed to be the common “stiffener” in the old-time bullet lubes. I’m sure that as an added benefit, it also raised the melting point of the lube itself. In warmer weather a greater portion of beeswax could be used so the tallow or sperm oil would not melt from the grooves of the bullet or inside the case. After returning home, I contacted a friend who was a beekeeper; he provided me with enough beeswax to experiment.

My first attempt was a mixture of four parts tallow to one part beeswax. I simply put the tallow and beeswax into a small pan and heated it over very low heat; when the mixture had melted, I stirred it and set it aside to cool.

Again, I placed a 3⁄8-inch wad of the lube between the card wad and the bullet, and smeared some of the lube in the grooves of the 457125 bullet. At 100 yards, I fired a five-shot group that measured three inches, and I was pleased. Again, I did not wipe the bore or blow through the barrel between shots. Each cartridge entered the chamber without undue resistance. The mixture not only worked, it was also slightly harder than the pure tallow, so it was easier to apply to the bullet and easier to shape into a wad.

One of my early favorite hunting bullets for my .45-110 was the Lyman 457121. Cast of 1:25 alloy (tin to lead), this bullet weighs about 460 grains. It has the flat point which I prefer for hunting, and has seven lube grooves. Its diameter is about .457 to .458 inch, which suits my old .45-110 just fine, since my rifle has a rather tight .457-inch groove diameter. I should also mention that the chamber of that rifle has about a half inch of freebore before the start of the rifling, which apparently was intended to aid with the seating of paper-patched bullets. This feature allowed grooved bullets to be seated out farther than the normal overall length, and provided the added bonus that a heavier powder charge could be used.

In reviewing my early notes on the .45-110, I referred to the performance of the 457121 in this way: “Excellent performance with either 1F or 2F. Card is pressed firmly on top of 90 grains of powder to leave adequate room for tallow and then bullet (also lubed with tallow.) This load will allow at least 10 shots without cleaning and without showing deterioration in accuracy.” The chamber of my rifle allows me to seat this bullet out so that the overall cartridge length is 3.75 inches. Velocity with 1F Goex was 1,245 feet per second (fps).

With that load, I have managed to take a large buck mule deer in Montana at distance of about 200 yards, and a whitetail buck in Kentucky at about 50 yards. A couple of attempts to take an elk with that rifle have not produced any meat. It’s the old familiar story of seeing only cow elk when having a bull elk license, or seeing only bulls while having a cow license.

Then, in 1996, I believe, I learned about the “Quigley Match,” a long-range buffalo rifle match that was being held annually on Al Lee’s ranch near Forsyth, Montana. Since my family and I were headed that way for our vacation, I decided to give it a try. By this time, I had experimented with many different homemade lubes, some containing mixes with Crisco, paraffin, Vaseline, mink oil, and other commercially available products.

“The Quigley” was definitely a learning experience for me. Back home in my part of Kentucky, only one or two of my shooting friends had any interest in the large black-powder cartridge rifles. At the Quigley Match, I was surrounded by them.

Now, I wasn’t a stranger to long-range matches. I had competed at Camp Perry, Ohio, many times in 1,000-yard matches, and in the 800, 900 and 1,000-yard Palma Matches. But that was with modern, high-velocity rifles. I knew that competing with heavy black-powder loads having a velocity of only around 1,300 fps was definitely going to be a challenge, especially in the Montana wind.

As I remember, the first Quigley Match I attended in 1996, had about 200 competitors. I felt like a new student in an advanced course on loading and shooting the old rifles. One important lesson I learned was the advantage of simply blowing through the barrel after each shot to help soften the fouling; this was not an exception among the competitors, it was the norm. Another was to keep the bullet lube fairly hard. I remember looking down at my ammunition while sitting behind my shooting sticks on the firing line and seeing the homemade lube (a mixture of Vaseline and paraffin) on my bullets beginning to melt in the sunlight. Another lesson learned.

I had added an Extra Long Range Vernier Tang Sight and a wind gauge front sight to my rifle before the match. With my wife, Linda doing the spotting for me (along with some timely help from other competitors), I managed about a 20th place finish in that match. And I had fun, lots of fun!

Before the next Quigley Match, I ordered a custom bullet mould from Paul Jones. My Lyman mould for the 457125 was simply a little large in diameter (.460 inch) for my rifle’s tight bore; it also had a very blunt round nose. As I had ordered, the new Jones mould cast a .458-inch bullet with 1:25 alloy, and its ogive was less blunt, which I believed would be less wind-sensitive at long range. It was also heavier and longer, weighing about 550 grains, compared to the 530-grain Lyman bullet.

Another big change for me was a switch to the new SPG Bullet Lube that so many shooters at the Quigley had been using. It seemed to have become the “gold standard” among black-powder match competitors, and I decided to give it a try.

Well, after those changes, (and a lot of practice shooting off the sticks) the .45-110 and I managed a third place finish in the 1997 Quigley match. I was hooked. I had another third place finish with the .45-110 in 2000, and I’ve always felt that my rifle’s primary limitation was the shooter firing it.

That old .45-110 has proven itself as both a match rifle and a hunting rifle. The match load that became my standard used a CCI Large Rifle Magnum primer, 93 grains of DuPont 1Fg, a card wad, a 3⁄16-inch lube wad, and the 550-grain Paul Jones bullet lubed with SPG, or a homemade lube, which seems to perform similarly. A few years ago, I retired it as a match rifle, and only use it now for hunting; its wind gauge target front sight has been replaced by a wide brass post front sight that I made because of its better visibility in low-light hunting conditions.

While writing this article, I loaded up some of my old .45-110 target ammunition and fired five shots at 100 yards, using the hunting sights. The only change I made from my old standard target load was to use CCI Large Pistol primers, which I now prefer, instead of the Magnum Rifle primers. After the fouling shot, the next four bullets grouped in just 17⁄8 inches. I figured the old rifle was still capable of performing just fine in long-range matches.

In recent years, I have used another, newer, C. Sharps Arms rifle in long-range matches. It is a .45-100 (2.6 inch), with a 32-inch round barrel, and it has a quicker rifling twist than my .45-110. However, for hunting, I still use the old .45-110 Sharps with the flat-point Lyman 457121 bullet over 90 grains of DuPont Fg (or Swiss 1½ Fg), a CCI Large Pistol primer, a card wad, a tallow/beeswax 3⁄8-inch wad, and the same lube in the bullet grooves. I wouldn’t change the tallow in my .45-110 hunting load for anything; it bespeaks tradition, and works well in the colder temperatures associated with most hunting seasons. After all, it was good enough for Elmer Keith, the one who gave me the idea, so, who could ask for more?

Now, before ending this article, let me share one of my favorite personal stories involving Elmer Keith and Sharps rifles.

The first time I visited Keith at his home in Salmon was in 1975. I was with a couple of friends, Glen Buckner and Larry Adkins and we had just finished a backpack elk hunt in Idaho, on which Larry had taken a very nice bull elk. I was hoping to meet Keith while we were in Salmon, and had gotten directions to his house from a waitress at a café while we were having breakfast.

The huge antlers of Larry’s elk were tied to the back of my Volkswagen camper as we drove up the hill toward Keith’s house and (as instructed by the waitress) turned left by the big evergreen tree that then stood on the corner of his street and near his house. He was coming out his front door when I saw him, wearing his big hat, a holstered handgun, and carrying what appeared to be a briefcase. The elk antlers must have made it obvious that we were on that street to see him, because, after glancing in our direction, Keith turned around and walked back into his house.

I parked and went to his front door and knocked. Keith opened the door, and I was face-to-face with the man whose writings I had admired for many years. I was a little nervous and blurted out something like, “Uh, Mr. Keith, my name is Harvey Pennington and I’m from Morehead, Kentucky.” His reply was fast: “You’re the one who called me at 6:00 one morning and wanted some loading information for 250-grain bullets in the .348 Winchester!” I admitted making that early-morning call, but, in my defense, I quickly explained that I had just gotten to my office that morning and had simply forgotten about the three-hour time difference between my home in Kentucky and his in Idaho.

He chuckled at my response and asked what I wanted. I said I had a book out in the Volkswagen that I’d like for him to sign, if he had time. He grinned and said he’d be glad to. Then he said, “Don’t you have a couple of other fellows out there with you?” I told him I did, and, without hesitation, he said, “Well, bring ‘em in!”

We had a fantastic visit. He signed his article for me in the book I had brought, and we talked for a few minutes in his house. Then he led us to a separate building behind his house that served both as a trophy room and an office. Elmer talked more to us out there, as we looked at his trophies and snapped a few pictures. It was interesting to me that he also busied himself at his typewriter while we looked around; apparently, he was wasting no time and answering correspondence from some of his readers.

At one point, when I commented on the size of a huge elk mount hanging on the wall, he explained that it was so large that he had to cut the skull in half so he could pack the head out, and, because of that, it couldn’t be officially scored for the record books; he still seemed aggravated about that.

When we were about to leave, Mrs. Keith came through the door; I recognized her from pictures I had seen, and spoke to her. She returned the greeting, and then asked if that was our Volkswagen camper parked in front of their house. I told her it was, at which time she informed us that we had a flat tire.

As we left, I asked permission to take a picture of the two of them together. They didn’t mind at all, and that picture, now framed, is still on display in our home.

While the three of us worked on the tire, Elmer came outside, dressed as I had seen him when we first drove up to his house. He came over where we were and chatted a minute. Having recently read his article on the Sharps rifles, I asked if he had a Sharps story that he could share before we left. He did...

Keith then told us a story about a friend of his who had accompanied him to one of the turkey matches in Challis, Idaho. They were one-shot matches at a distance of 100 yards, with the winner being the person who shot the closest to center. Elmer was shooting the old .45-100 Sharps that had belonged to Hank Waters during the hide-hunting days.

Because Keith had won too many of the first matches that day, the person acting as the match director went to Keith and told him he had been “disqualified.” Keith didn’t protest his disqualification, but did ask whether someone else could shoot his rifle. The director said he thought that would be okay.

Keith then asked his friend to shoot in the next match. According to Keith, his friend wasn’t all that anxious to shoot the old Sharps, but finally agreed to sit at the bench and follow Keith’s instructions as to how the sights should be lined up on the target, and then dry-fire it. Well, when his friend left the shooting bench to tell his wife what he was about to do, Keith said he took the opportunity to slip one of the big cartridges into the chamber and closed the action. When his friend returned, Keith had him sit down at the shooting bench, talked him through how the sights should line up on the target, then told him to cock the hammer and pull the set trigger; he again reminded his friend to be sure the sights were perfectly aligned and to gently touch the front trigger.

Of course, when the rifle discharged, the resulting blast and recoil took Keith’s friend by complete surprise. He was enraged that he had been tricked, and Keith said it took his friend a long time to get over it. Then, after a little pause, Keith looked at us and said, “But, you know what?” I shook my head, and waited for him to continue. Keith smiled and said, “He won that match!”