Loading by the Batch

feature By: Steve Garbe | April, 18

Unfortunately for rimfire shooters, searching for the perfect lot of ammunition is an unending quest, as reloading for the .22 is for the most part a nonstarter. There are those (and I am one) who have dabbled with juggling components and custom loading for their rimfires, but this is really the exception and not practical or legal for many competitions.

My personal choice is loading my ammunition “by the batch.” When I say “by the batch” I mean taking one can of powder, one tray of primers, 100 weighed and inspected bullets and loading 100 rounds of ammunition. One pound of black powder will generally load 100 rounds of my favorite .38, .40 or .45 black powder cartridges. Of course, if one is loading for some of the larger cartridges, 75 rounds may be the limit. The idea here is to make up a “lot” of cartridges that will be used consecutively in a match. It goes without saying that these lots need to be loaded using cases of all the same headstamp, and preferably from the same run, annealed and checked for length. When switching lots, sight settings should be checked and regulated for the new ammunition.

Each lot is contained in a 100-round box and is numbered and dated for easy reference. I also keep track of the number of times the brass has been annealed, sized and reloaded. The cartridges will not be combined with others for cleaning. In short, these cartridges will always be handled, loaded and shot in a batch. I do not even fire the cartridges in a different rifle; each rifle has its accompanying cartridges and they are not used in other rifles. In this way I reduce the possible ways that variation can sneak in to my reloading and shooting. Each rifle is an individual, even if the same chambering reamer has been used in production, so keeping all components specific to the rifle is simply the smart way to monitor changes in the brass over repeated firings.

The first thing that must be done in batch reloading is to admit that there is variation within components. I’m not talking about

Generally, there is a lot number on the label of a can of black powder. This allows a handloader to at least identify different lots of powder and not mix them. I started buying my black powder by the case long ago to ensure that at least the propellant was from the same run of powder. I also didn’t want to do load development constantly because of velocity variations between powder lots.

If local regulations restrict you from having that much black powder on hand, at least buy it in 5- to 10-pound amounts to cut down on lot variation. However, I still think the best course is to treat each can as an individual and not to mix cans in the same batch of ammunition. Black powder today is much more uniform, lot to lot, than it was even 20 years ago. Generally speaking, one doesn’t have to check load velocity when changing lots of powder, but I still do. I want to know exactly what velocity I’m getting. This is more of an issue with long-range shooters, where even a few feet per second can make for big sight changes. Every once in a while, a batch of powder will show up that has different fouling characteristics and this needs to be addressed as well. All these things point back to the wisdom of when a powder that works is found, get as much as can be afforded and legally stored.

In days gone by when I used to screen black powder, it was noticed that certain cans within a case would have more “fines” than others. However, within the last few years I have noticed that the better grades of black powder are much more closely screened and so I have quit that procedure. Black powder is like all things in life – you get what you pay for. Cheap powder will not be screened closely and this really can affect uniformity of ammunition. In order to make top-quality ammunition, one needs to use the best components. An easy check for fines in powder is to pour off the top half of a can onto a sheet of white butcher paper. On a different sheet, pour off the bottom half. If there are a high percentage of fines, it will be easy to see it on the white paper.

Primers that have been improperly stored and subjected to wide swings in temperatures can introduce variation. Remember that fact when buying primers on the second-hand market. Given primer scares over the years, and relatively good supply now, there are many individuals selling old batches of rat-holed primers. If they have been stored out in the garage, subjected to intense summer heat and cold winter temperatures, they will not be as consistent as new primers from the manufacturer. I’ve actually heard guys at gun shows talk about filling up partial trays of primers with others of the same size designation in order to sell them. Regardless of price, these are not primers that are good for load development or match ammunition. Primers also have a lot designation; always use primers from the same lot when loading ammunition batches.

Lubricant can be another source of ammunition variation. Bullet lubricant can vary between batches and storage becomes a real issue with specific lubes. Some great lubricants only work well when freshly made and properly stored. A lubricant that has “gone south” is readily apparent when excessive leading rears its head. Probably more lubricant has deteriorated from improper reheating than from any other cause. Always use a double boiler to heat lubricant and avoid using a microwave as well. Those 30-year-old sticks of lube that you found for a bargain price at the gun show? There’s no free lunch when it comes to bullet lube; buy it fresh from the manufacturer or a reputable dealer who knows how to store it. Mixing brands of lubes because “I’ve got some left over and don’t want to throw it out” is seriously false economy. You might get lucky and come up with the next new Super Lube

. . . or you could lead a barrel on rams and lose that important match. I think you get the picture.

Another variable that many riflemen do not consider is reloading tools. Dies and reloading presses can introduce serious run-out on loaded rounds, which is disastrous to ammunition quality. Here again, we get what we pay for and the best course is to not scrimp on dies or presses. I prefer inline seating dies cut with the reamer that chambered my rifle. These are used with an arbor press and greatly eliminate loaded round run-out. If a reloading press is used with stock dies, be very conscious of the slight change in “feel” when sizing, expanding and seating. If a case or loaded round feels different in any of these operations, that round is marked and used as a fouler or a rough sighter. When seating bullets with factory dies, lightly start the bullet, and then give the cartridge a half-turn before seating all the way. In this way, it’s reckoned the run-out in seating stems or in the press ram itself is cancelled. It’s easy to get the knack of feeling your reloading tools work and this is a great way to enhance ammunition quality.

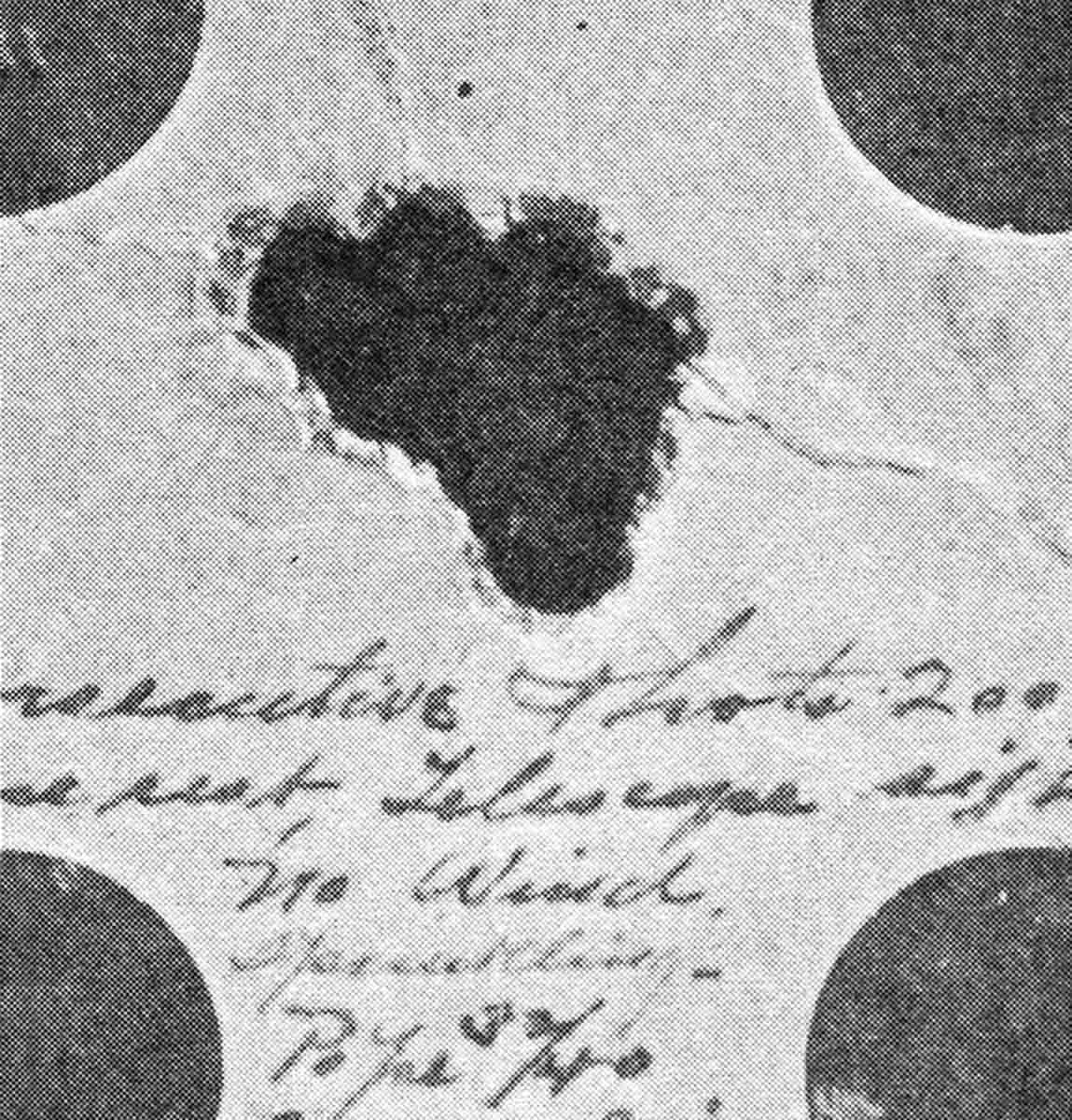

When it comes to bullets, the “batch” concept holds true as well. I typically cast bullets in lots of 120. It seems like that number represents about the most I want to cast at one sitting, and it provides plenty of bullets for loading a batch of ammunition. Index bullets out of the mould, marking the base with a very slight scribe mark, which allows the bullet to be oriented by the casting line closest to the mark. I know that many bullet casters put an indentation in the bullet mould’s nose cavity, but I find it hard to do this after the mould maker took the pains he did when cutting the mould. Keep bullets segregated in the order cast and load them into the cartridges in that sequence. It goes without saying that the bullets are all weighed for uniformity. The bullets are put through the lubri-sizer (if one is used) by the index mark and loaded into the cartridges the same way. I shoot them in the order cast as well. Some would say that these are unnecessary steps, but if nothing else I’m following that rifleman’s mantra: “Consistency Is Everything.” I would point out that Charles Rowland, the rifleman responsible for the long-standing record of 10 shots at 200 yards into a .725-inch group, did the same procedures. Rowland was well known among the serious shooters of his day for his attention to detail and his obsession for extreme accuracy.

Batch loading promotes the removal of variation, and that simple but hard to attain fact greatly enhances accuracy. Ammunition that is known to be consistent is a huge confidence builder and is absolutely critical to good shooting. Knowing that your rifle and ammunition are free from serious variation leaves only you, the shooter, as the determining factor in a successful match.