Making an 8-Bore Westley Richards Explora Shoot

Fear and Loading with 273 Grains of Black Powder

feature By: Mike Stumbo | February, 21

My consultant had dropped his previous Cape buffalo with another relic from the early days of safari, a lever-action Winchester Model 1895 – Teddy Roosevelt’s “medicine gun” for lion. Because factory .405 Winchester ammunition is light for buffalo, I had worked up handloads that made his rifle perform on par with the .375 H&H Magnum. This, plus 50 years of reloading experience, made me a prime candidate to develop ammunition for the 8-bore, too. Black-powder cartridges are not available at Walmart (or even Cabela’s) and the specifications for this gun’s fodder had been lost. The cleaning and reloading tools, which Westley Richards had supplied with the rifle in its original leather case, were long gone as well. To make a double rifle shoot properly (to put both its barrels on target in what are charitably called “hunting groups”) takes some finessing. In this case, since we couldn’t regulate the barrels – change their relative positions, as the maker can do – our only option was to fuss with the cartridges until we came up with a case-primer-powder-wadding-bullet assembly that this “cannon” liked. Double rifles are finicky beasts.

Technically, however, a Westley Richards Explora is not a true rifle; it is a smoothbore with, shall we say, a twist. On June 20, 1885, Col. G.V. Fosbery, V.C. (ret.) patented the concept of rifling the last six inches or so of a shotgun bore. The result was a good shotgun and, out to about 150 yards, a decent rifle – something that could be equally effective on birds and four-legged game. Holland & Holland bought the patent from Fosbery and introduced its version of these guns under the name “Paradox” and offered them in sizes from 28 gauge to 8 bore. (If you’d like to follow-up, David Baker and Roger Lake wrote the definitive book, titled Paradox: The Story of Col. G.V. Fosbery, Holland & Holland, and the Paradox.)

Sales of “bore guns,” the black-powder 10-, 8-, 6- and even 4-bore artillery that hardy souls carried to the farthest corners of the Empire fell off quickly when Nitro Express cartridges arrived, just before the Great War. Nitro Express rifles fired smokeless powder, weighed just two-thirds as much, recoiled less, but killed as well or better and cost no more. It was an easy choice. Twelve-bore and smaller Fosbery-patent guns transitioned to smokeless powder, but efforts to create 10- and 8-bore smokeless loads were abandoned because the black-powder ballistics couldn’t be duplicated and because the big cartridges were made obsolete by the Nitro Expresses.

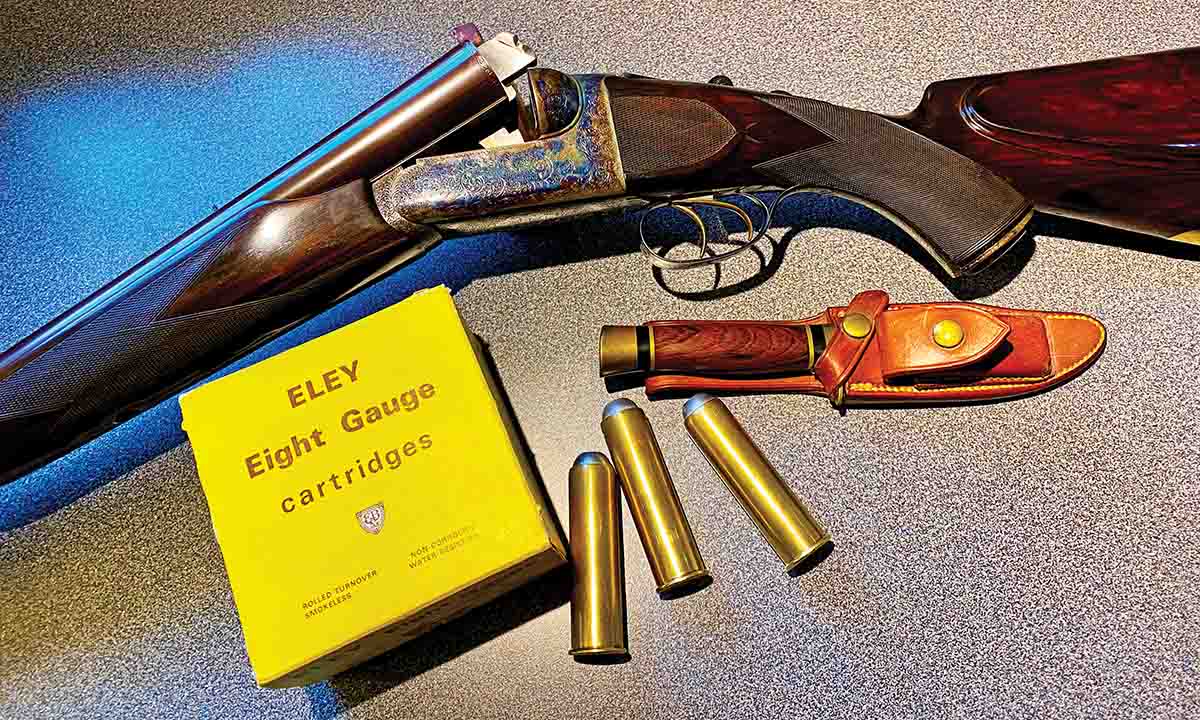

The current owner has not fired the big Westley. The previous owner had, but unsuccessfully. He kept a neatly organized notebook of his attempts – 30 pages of shooting sessions, each one of which resulted in bushel basket-sized groups. This was somewhat helpful because it showed us what not to do. Still, we began the 8-bore project with no cases, no bullets, no dies, no reloading instructions and little experience with black powder. But soon word-of-mouth turned up 10 beautiful 31⁄4-inch brass cases, apparently CNC-made and ours for only $10 apiece. Now, what to put in them?

First, bullets: None were available online – hardly surprising – but we found Accurate Molds, in Salt Lake City, Utah, which offered a single-cavity mold for a 993-grain (2.27 ounce) 8-bore “paradox” bullet. Fitted with RCBS handles, the mold cast seemingly perfect bullets right out of the box. I pan-lubed them in the kitchen (my wife was at the office) with SPG Lube.

Roger Lake, co-author of the Paradox book, told us that a bare bullet should just drop through the smooth part of the bore and then hang up at the start of the rifled section, near the muzzle. But our bullets stopped at the forcing cone, about 20 inches before the rifling. The answer was a sizing die – bored out on my vintage South Bend lathe – to reduce the bullet diameter from 0.835 inch as cast to 0.829 inch. With great difficulty, I was able to push one bullet through it with a heavy bench vise, then moved to a large hydraulic press, which handled the process smoothly. The sized bullets slid satisfyingly down the bore to meet the rifling.

Now the loading dies: Given that the 8-bore case is just about 7⁄8-inch in diameter, a standard 7⁄8 x14 tpi die would not work. I have an old Hollywood turret press with three 1½-inch stations in addition to nine standard 7⁄8-inch stations. Theoretically, I could have created dies for the larger stations and somehow fashioned a shellholder. But we figured we’d be loading cartridges in camp in Africa, just as it was done a century ago. So, I set out to make the rest of the tools we’d need, inspired by the photos in the Paradox book and an old mallet, measure & punch-type Lee loader leftover from my long-ago college days.

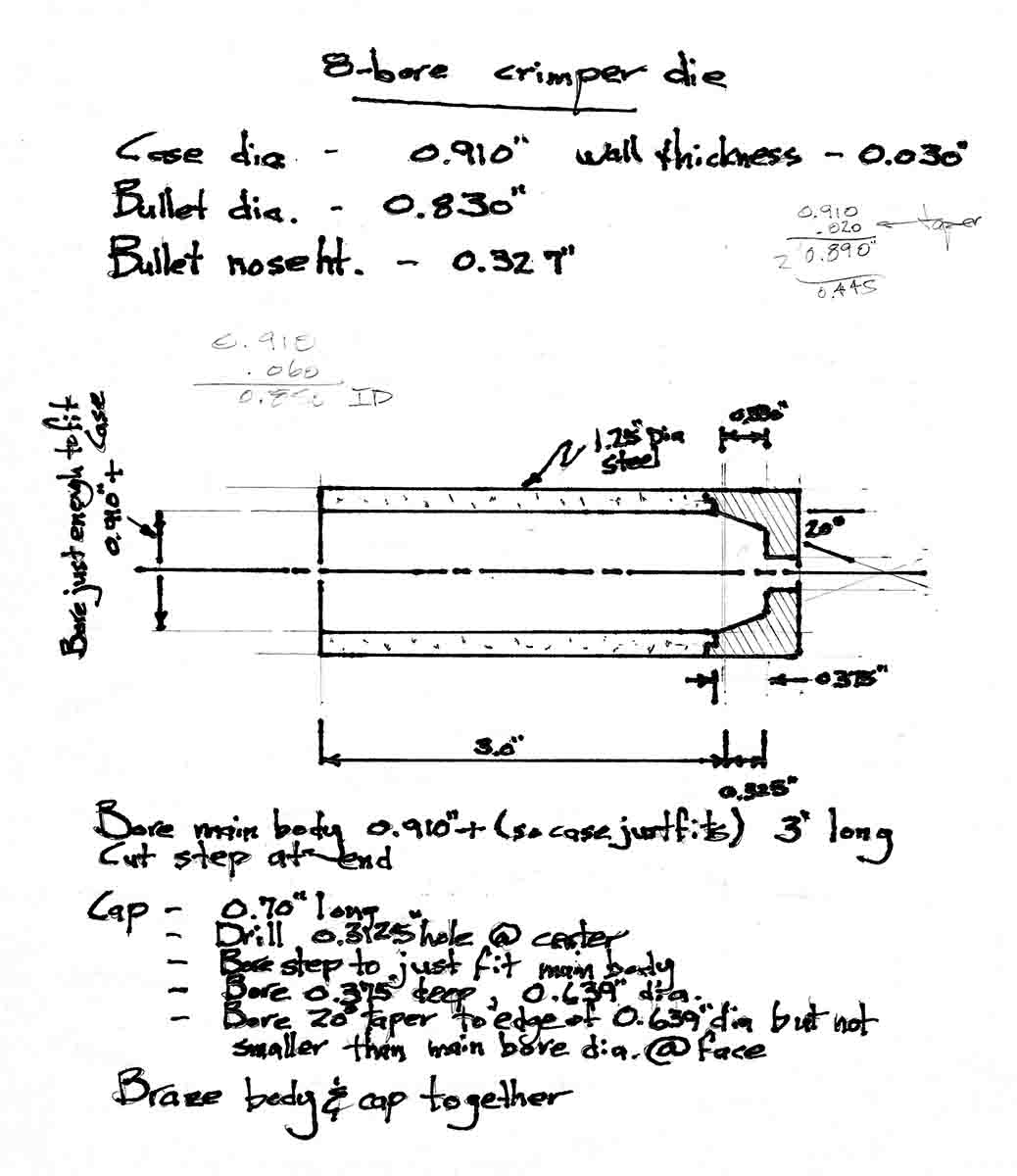

The biggest challenge was the crimping die. The bullets dropped into the cases even before they were sized down for the barrels; but of course, they had to be fixed in their cases, and securely too, to prevent them from moving under recoil when the other barrel was fired. I had to make a die that slipped over a loaded bullet – sitting loosely atop the powder-and-wad column – to crimp the mouth of the brass case around it.

Working from precise bullet dimensions, I machined a flat at the bottom of the die that would stop at the flat top of the bullet and tapered the inner wall of the die to make a self-centering forcing cone that would push the case rim into the bullet below the flat. To support the case and make sure the crimp was even and square, I made the die nearly as long as the 3¼-inch case. Because my tooling couldn’t reach deep enough into the die to cut the taper, I had to machine the die in two pieces and braze them together.

I bought a selection of wads – card, fiber and Oxyoke – from Buffalo Arms and Precision Reloading. From a one-inch aluminum round, I made a selection of powder measures. I also created a drop tube. Then, with all this in hand, it was time to assemble our first live rounds.

Loading begins with starting a 209M shotshell primer into the case by hand. Then, set the case on a maple block, insert a punch (also maple) into the case and tap it with a mallet to seat the primer. Now measure out the powder charge and transfer it into the case via the drop tube.

With the powder in the case, carefully stack enough wads on top so that when the bullet is added, its upper bearing surface (the flat belt, or sidewall) just protrudes above the case. (I put card wads on the powder and Oxyoke under the bullet.) Lightly wipe the outer rim of the case with wheel bearing grease.

Then, with the filled case still on the maple block, slide the crimping die over it and lightly bump the die with a two-pound hammer. This compresses the powder and wad column slightly, seats the bullet to the correct depth in the case and crimps the brass around it.

The gun bears proof marks for 10-drams of black powder. Not being complete idiots, we decided to start with seven. First, though, we fired a primed case in each barrel to check ignition – the trigger-sear-striker-firing pin linkage. Next, we put a loaded round in one barrel and a primed case in the other, fired the loaded one and checked the primed round to make sure the rifle hadn’t doubled. Then do it again with a live round in the other barrel. In the event, the lockwork and ejectors functioned properly.

Our plan was to shoot safari-style, off sticks – basically a tripod held together at the top with shock cord – at 25 yards, stalking distance in the Mahango area of the Caprivi. But the exceptionally wide forend (a good three-inches across) forced the tripod too far apart and lifted one leg off the ground. My friend the consultant, ended up shooting the gun – 16 pounds loaded – offhand. His group was encouraging, but inconclusive. And we had only four rounds, reckoning that was enough punishment for him for the day.

The next time we went to the range, we had 7-, 7½- and 8-dram cartridges, a portable stand-up shooting bench, plenty of sandbags and a chronograph. Namibia stipulates a minimum of 5,400 joules, essentially 4,000 foot-pounds of muzzle energy for shooting dangerous game, and with a 993-grain slug we needed just over 1,300 fps to meet that requirement. That would deliver roughly .375 H&H Magnum terminal ballistics, but a Knock-Out Factor (John Taylor’s formula) of fully 158, edging out a .600 Nitro Express.

We got to about 1,250 fps before muzzle blast and flying wads knocked down the chronograph and broke one of the reflectors. Worse, though, was that while the “light” 7-dram loads had grouped at more or less buffalo heart-size, the heavier loads crossed into successively wider groups. (Double-rifle barrels are regulated to converge at some point downrange.) By now, recoil was taking its toll too, and my shooter was icing his cheek with fistfuls of Maine snow.

Another problem arose when I found I couldn’t reload the empties on-site because my crimping die wouldn’t fit over cases that had been expanded by firing. But later on, when those problems had been solved, our next loads didn’t group any better. One round even misfired, probably because I had dipped into an old box of primers. At least it was an opportunity to see if my shooter was flinching. Not yet.

So, it was back to the shop to try to figure out what to try next. My shooter happened to have double-gun expert Ross Seyfried’s email address, and when I wrote to him under the title “8-bore questions,” Ross responded quickly. He listed the many idiosyncrasies of loading for big Fosbery-patent guns and ended by noting that they only shoot well with their proof loads – in this case, a full 10 drams (2731⁄2 grains) of black powder: “With all of these things absolutely correct the bullets should touch, or nearly at 50 yards. Sometimes these guns shoot high because of the way they were originally sighted, and a new front sight corrects that.”

The recoil, Ross added, would be “monumental – if you are unprepared to feel like you were just in a plane crash, consider a smaller gun.” This gave my friend something to think about as we prepared for the next round of testing. He calculated our full house rounds would produce 140 foot pounds of recoil.

Speaking of self-inflicted injuries, I then did the stupidest thing I have ever done in decades of problem-free reloading. Thinking to salvage the bullet and the rare brass, I tried to extract the primer from the misfired round while it was intact. I have loaded tens of thousands of cast bullets for pistol competition and occasionally encountered a bad primer. I also learned that while it’s easy to extract a jacketed bullet with an inertia puller, it is nearly impossible to pull a taper-crimped cast bullet. Assuming it would be the same with this 8-bore round, I left the bullet alone and tried to lift the edge of the flange of the primer and grab it with a small vise-grip. Realizing that this entailed some risk, I had the round buried to the rim in my heavy bench vise and was wearing welding gauntlets and a face shield. I almost got away with it.

The primer was nearly out and had gone through some fairly rough handling, so I figured it was dead. Shedding my gauntlets and face shield, I switched to an awl to lift the primer that last fraction of an inch. What seemed like the lightest touch set if off. Because the case was deep in the vise, the brass and lead shrapnel fanned out to the sides and missed me entirely. But the awl came back into my hand so hard that it bent the steel shaft 90 degrees, lifted a big flap of skin from my palm and split the tip of my finger. My trigger finger. There was blood all over before I found a clean rag. I drove one-handed to the emergency care center, where I got six stitches in my palm, two more in my finger and a tetanus shot. Still haven’t told my wife the details . . .

A couple of weeks later, when my hand was semi-usable again, I returned to the workshop to solve the remaining problems and load more test rounds. I opened up the ID of the crimping die so that it fit over a fired case (and a reloaded round would drop out easily after crimping). I assembled four rounds with the 10-dram charges Ross had recommended, plus new 209M primers. I must say, by now my finished cartridges were beginning to look factory-fresh. Then it was back to the range for a final test session. This would be our make-or-break moment; if the gun still didn’t shoot well, my consultant would have to rethink his vintage-weapons concept. (A spear, perhaps?) I had also used the downtime to make a shot-filled leather sock to fit over the butt of the Westley, to help tame the recoil.

In truth, we were expecting that the even heavier charge would make the cross-firing even worse. Much to our surprise, at 25 yards the gun grouped beautifully. As Ross also had predicted, the group was a few inches high. If the gun belonged to either of us, we would correct this with a taller front sight. But it doesn’t, so my shooter will have to hold a bit low. (Hope he remembers that when the balloon goes up.)

His reaction when four right-and-left rounds almost touched was, “It worked! Damn, I guess I will have to shoot this thing.” The shot-filled sock had increased the length of pull and tamed the bruised cheek problem, but the recoil still knocked him a bit shaky. The cast bullets (one-part tin to 15-parts lead) went deep into the dirt but looked like they’d kept most of their weight. The boom of the big gun brought the range safety officer hustling out of his office, thinking someone was tearing up his berms with a cannon. He hefted the Westley and was suitably awed by the cigar-size cases.

Now in March, we had a working load and we were 10 weeks out from Africa with time to get everything else together and do some physical conditioning . . . and then COVID-19 arrived. In April, Namibia closed its borders to foreigners through September. We have rescheduled for late May 2021, which is fall in the Caprivi and the middle of the kudu rut. Let’s hope that both of us are still healthy then and that things are returning to normal. I am disappointed to miss my once in a lifetime safari this year, but that’s a petty problem with people dying around the world.