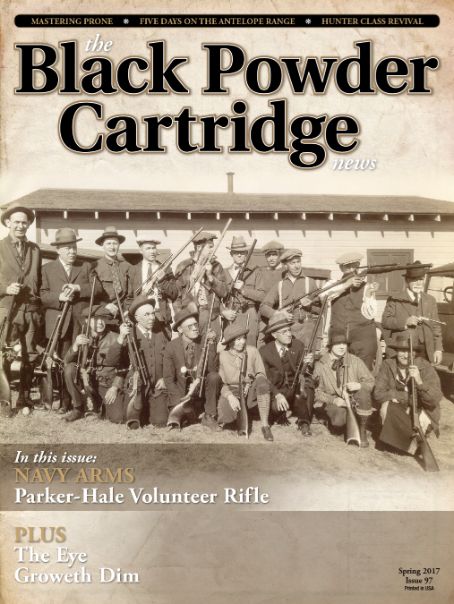

The Navy Arms Parker-Hale Volunteer rifle.

One of the most interesting aspects of the Civil War involves the blockade of Confederate ports along the southern coastline of the United States. The blockade, ordered by Abraham Lincoln and carried out by Secretary of State Seward, had an immediate effect upon countries across the Atlantic Ocean, especially England. The textile mills in England were dependent upon the cotton produced by the South to keep their factories running. Deprived of the cotton, the allegiance of Great Britain swung to the Confederacy, which should be no great surprise given the relationship between America and England from 1776 to the 1860s. The blockade was effective, but only to a point. Throughout the duration of the war, on average only one out of every six blockade-running ships was caught. It is estimated that as much as 540,000 bales of cotton were smuggled from the South to England. However, not only was cotton smuggled out, just as much in the way of goods were smuggled into southern ports, including meat, coffee, luxury items and a lot of firearms. Although the English textile mills may have seen some difficult times due to the inflated price of cotton, the armsmakers of England flourished. Huge quantities of arms were shipped to the South. Skippers of blockade-running ships made huge profits, especially the British skippers, and often made this toast:

“Here’s to the Confederates that grow the cotton, the Yanks that keep the price up by the blockade, the Limeys that pay the high prices for it – to all three and a long war.”

The established process for the smugglers was for the big British steamers to unload their cargo at Nassau or Bermuda and take on cotton for the return trip to England. The cargo from England was then smuggled into southern ports by sleek, fast-moving, low-draft ships painted gray or black, slipping in under the cover of darkness. Arms smuggled into the South included British muskets, Austrian and Brunswick rifles, as well as various carbines and cannons. But, by far the greatest types of firearms

smuggled in were Enfield rifles. For example, in November 1861, a single ship brought in 7,500 Enfield rifles along with 17,000 pounds of cannon powder. In 1863 some 80,000 Enfield rifles made it through the blockade, with even more in the following years. The majority of the Enfield rifles were the Pattern Model 1853, 3-band rifled muskets, but also included were the famous Whitworth rifles and the Pattern Model 1856 Sergeant’s 2-band short rifle, also known as the “Volunteer” or the “Navy” rifle.

The Enfield 2-band Volunteer rifles were commercially produced based on the military design. They were sold to British civilian “volunteers” serving in the militia, or to be used for target shooting, or as a sporting rifle. This was much in the same manner as one could purchase a military rolling block rifle from Remington here in the U.S.A. Volunteer rifles were made not only by Enfield but also several other makers, including Alexander Henry and Sir Joseph Whitworth. Most of them

were .58 caliber (.577) and included a variety of rifling styles. From what I have been able to ascertain, most were rifled with the same three-groove, one-in-78-inch twist as the Pattern 1853 Enfield. Around 1861, the Volunteer rifle was given a heavier barrel having five grooves and a one-in-48-inch twist. Other styles of rifling were employed by the various makers. For example, Alexander Henry used his own style of rifling in his guns. The one thing that seems to be a common thread among all the rifle makers was to use progressive rifling wherein the bore tapered toward the muzzle approximately 0.010 inch.

The first reproduction Volunteer rifle I owned had Alex-ander Henry rifling and was in .45 caliber. Although it seems the majority of Volunteer rifles were made in .58 caliber, there were others. I have a friend who owns a Pattern 1856 rifle made by Alexander Henry in .451 caliber. Its configuration varies a bit, and it is fitted with original target sights. It is a fine example of what was being produced in England in the mid-nineteenth century.

The Parker-Hale Volunteer

Alfred G. Parker and Arthur Hale established the Parker-Hale Company in Birmingham, England, in the late 1800s to furnish shooting supplies to target shooters, gun clubs and British Volunteers. Later on, the company produced a variety of rifles, mostly of small caliber intended for target shooting and hunting. However, in the 1970s, Parker-Hale started production of the

Lyman bullet mould 451114AV for the Navy Arms Volunteer rifle.

P53 (Pattern Model 1853) Type IV Enfield Rifle such as had been produced more than a century before by the Royal Small Arms Factory for the British

War Department. Parker-Hale took extensive measurements of Enfield rifles at the Royal Armoury Museum and was even allowed to borrow a set of original Enfield master gauges from the museum, of which they made exact copies. The company produced the full-length 3-band rifle, the 2-band short rifle and the even shorter carbine. I remember seeing a 3-band 1853 Parker-Hale in the late 1970s and drooling over the quality of the rifle. But, being in my mid-20s and with a young family to support, I could not afford one of the Birmingham-made Parker-Hale Enfield rifles. Fortunately for me, a decade or so ago, I found a Birmingham Parker-Hale Model 1853 in a local gun store. It is serial number 5464, making it one of the

Pinhead-style front sight on the Volunteer rifle.

early ones, probably made in 1979 or 1980.

It can be argued that Parker-Hale Enfield Volunteer rifles were not reproductions but rather a century-later continuation of production, since the nineteenth-century Volunteer rifles were produced by a variety of makers. The Parker-Hale rifles were produced using a duplicate set of original master gauges, similar to what Colt did in bringing back the 1851 Navy revolver during the same era. The production of Parker-Hale Enfield models lasted for a couple of decades and ended when the company sold the Parker-Hale name to Euroarms in Italy. Euroarms did produce Parker-Hale labeled rifles, but the quality was less than what had been produced in Birmingham by Parker-Hale.

Euroarms went out of business in 2011 when the company was acquired by Davide Pedersoli Company. Subsequently, original Birmingham-made Parker-Hale Enfield rifles have become collector’s items in their own right and command the highest prices of any twentieth-century produced Enfield percussion rifles. For a time there was a void in the production of the Parker-Hale line of Enfield rifles. Such is no longer the case.

The Navy Arms Parker-Hale Volunteer Rifle

Val Forgett III of Navy Arms Company, along with Davide Pedersoli Company, has brought back the Parker-Hale Volunteer rifle

Traditional military rear sight.

and the Parker-Hale Whitworth rifle. Last year I had the pleasure of visiting the Pedersoli factory in Italy, and one of the many rifles I was privileged to see being produced was the Parker-Hale Volunteer rifle. After returning from Italy, Navy Arms sent me a Volunteer rifle to test and review. Although the rifles are manufactured in Italy, some of the final finishing is completed by Navy Arms here in the U.S.A.

As one can see from the photos, the Navy Arms Parker-Hale Volunteer rifle is very well made. The stock is made from American black walnut into which the furniture is inletted very well. Additionally, the wrist and the forearm are checkered to match the Volunteer rifles produced by Alexander Henry and include the Parker-Hale cartouche on the right side of the buttstock. The buttplate, trigger guard and nose cap are polished brass. The hammer, lock

This 50-yard, five-shot group measures 2 inches, shot with the Navy Arms rifle from benchrest.

plate and barrel bands are hand-finished in the U.S. using the bone-charcoal method of color casehardening.

The barrels are made by Pedersoli and, as previously mentioned in prior articles, I was able to see how they are made. All Parker-Hale barrels are con-toured outside, bored inside and then checked for straightness. From there, the barrels are rifled with Ballard-style rifling and finished with a process that results in the rifling having a slight taper from breech to muzzle just as were the original barrels. In comparing the Navy Arms Parker-Hale to my original Parker-Hale 1853 model, I find it to be of equal quality in every respect.

Testing the Navy Arms Parker-Hale Volunteer Rifle

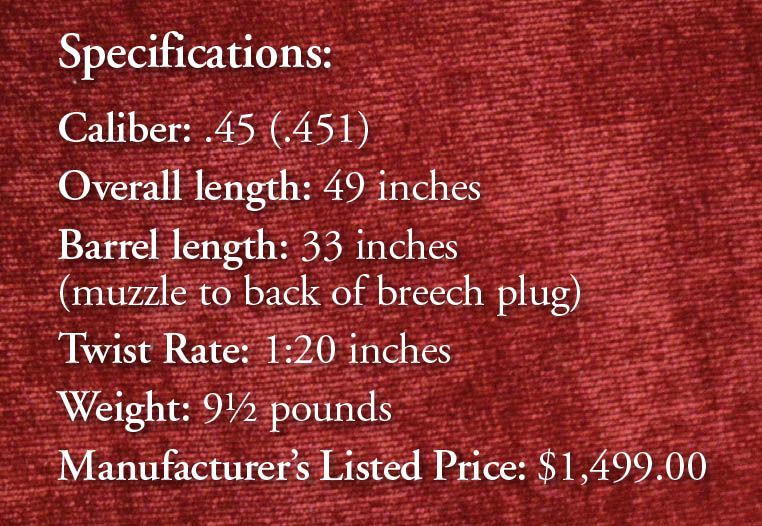

The Volunteer rifle is .451 caliber for which Lyman makes mould 451114AV. Bullets cast from my mould using pure lead weigh in at 446 grains. The bullets were run through a .4515-inch sizing die (the nearest to .451 inch I have) and lubed with SPG bullet lube. Navy Arms recommends using a soft muzzleloading lube, such as TC Bore Butter.

This 100-yard group measures slightly over 2¼ inches.

As for powder, I chose to use Olde Eynsford FFg Royal Blend Black Powder as it just seemed appropriate for a British rifle. However, any quality black powder or substitute should perform as well. In my experience over the years of shooting muzzleloading target rifles, both for ball and bullet, a charge of 80 grains in a .45 has proven to give accurate results out to 100 yards. Prior to loading, several caps were fired into a seated cleaning patch to remove oil in the breech. A charge of black powder, with the measure set to the 80-grain mark, was poured through a brass funnel into the bore. Next a .45-caliber felt Wonder Wad was doped up with Bore Butter and started into the bore. Starting the bullet in the muzzle was difficult with just thumb pressure, so I wound up using a short starter to push the bullet into the bore. The bullet was then carefully seated on the powder charge with minimal pressure.

A dozen or more shots were fired to get the feel of the rifle from the benchrest. The military sights, although appropriate for

Volunteer buttstock with the famous Parker-Hale cartouche.

the rifle, are not the best for target shooting, nor are they designed to be. Several five-shot groups were fired at both 50 and 100 yards. The bore was wiped with a wet patch followed by a dry patch after each shot.

At 50 yards the best group meas-ured 2 inches vertically and 1¼ inches horizontally. Three of the shots went into a ¾-inch group. Had one shot not been high, which I attribute to the large pinhead front sight, the group would have been just over one inch in size. At 100 yards the best five-shot group measured just over 21⁄4 inches due to one shot striking a bit high. The other four shots measured 13⁄4 inches at the widest bullet hole centers.

The rifle fired perfectly every time with quick ignition; no misfires what-soever. The

trigger pull is crisp and estimated to be about 21⁄2 pounds. Recoil is what one would expect from a heavy bullet and powder charge – not punishing, but enough to let one know he’s shooting a big rifle.

The Navy Arms Volunteer is an excellent copy of the Parker-Hale rifle, which in itself was an accurate rep-resentation of those made by Alexander Henry and others, patterned after the British Enfield. In my opinion, it justifiably deserves its markings of the Parker-Hale cartouche in the stock and the Royal Crown on the lock plate, underscored by the letters “P-H.” C

See ya at the range,

– Kenny Durham