Shooting the .32 and .38 Smith & Wesson

feature By: Mike Nesbitt | December, 21

Historically, Smith & Wesson’s real foundation rests on the small revolvers, not its big guns. Remember that S&W got its real start with the .22 tip-up revolver. The .22 was expanded, so to speak, to become the .32 rimfire, which, in the No. 2 revolver, paved the way very well for other guns. Yes, the Russian contracts for the .44-caliber guns certainly helped the business, but it was still the small guns where S&W’s future lay.

Our personal interest in these little guns was rekindled fairly recently when Lynn came back from Wyoming with one of the Second Issue .38s with the rather rare 5-inch barrel. We kidded each other about what we’d do with that or similar guns, just like we did back in the 1960s, but the urge to have and shoot the old top-breaks came back like a flood; and that meant that I’d need one, too, which didn’t surprise either one of us.

Scouting around turned up a couple of the First Issue .38s (the Baby Russians) plus a Second Issue or two, but what I decided to get was one of the little .32s, and I got one with the 3½-inch long barrel. This gun was nickel-plated, as so many of them were, and some of the original plating still remains. While this .32 is not in new condition on the outside (being just over 140 years old) it still functioned nicely and the barrel showed wear but no pits or other damage. So the little .32 became mine and I can easily say that it delights me.

With these two old top-break S&W revolvers begging to be used, we both retired to our respective “base camps” and began to prepare some ammunition worthy for our five-shot revolvers.

For my .32 S&W, I got a set of dies from Lee Precision. Those seem to work quite well and the set of dies came with the proper shellholder. Getting a bullet mould was simple enough; Lyman still catalogs and makes its No. 313249, which is one of the old styles made years ago for the little S&W cartridge. That bullet is listed at 85 grains and only one of the bullets cast from my mould with 25:1 alloy of lead and tin was weighed, with the scale balancing at 83½ grains. Along with that, I also got a .314-inch bullet sizing die, but instead of using the sizer, I find that it’s easy and preferable to simply pan lube the little .32 bullets.

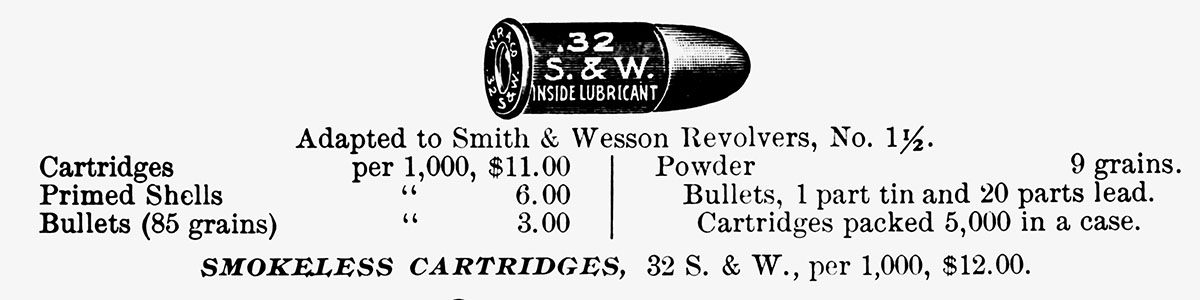

Next, a load had to be figured out for the new .32 S&W cases that were made by Starline. Old books were consulted, but even the oldest loading manual showed nothing but smokeless powder loads and, just to give a good example of how small the .32 S&W is, a recommended load using the little Lyman bullet was listed with only one grain of Bullseye powder. I was able to find good information in my old copy of the Lyman Handbook #29. (Every black powder reloader should have one of those!) For some guidance on a black-powder load, I turned to old catalogs and cartridge boxes. In the 1916 Winchester catalog, the .32 S&W is listed with 9 grains of black powder and on some of the older ammunition boxes where the powder charge is shown on the label, some of the loads, by UMC I believe, used 10 grains of powder. That gave me something to go on.

My first try at loading the .32 S&W with black powder used 7 grains of Olde Eynsford 3Fg under the .32-caliber Lyman bullet. That needed too much compression and the bullets simply couldn’t be seated. Perhaps I could have made and used a compression die, but I wanted to keep things simpler than that. So, I reduced the loading to 6 grains and still had the same problem. Following that, the loading was cut down again, to just 5 grains of powder, after switching to 2Fg (for no particular reason), and with that, the powder is still compressed slightly when seating the bullets, but it is slight enough that the bullets in the loaded cartridges are not deformed.

But it was still a lot of fun and it was certainly black-powder shooting, complete with the small cloud of white smoke…and the accuracy was actually pleasing. We conducted a little test, making it practical by bringing the targets fairly close to these little revolvers by shooting from about six yards. With a rather small bullseye, five shots were fired while holding the little gun over a rest. Delightfully, four of the five shots went through the X ring while the other shot, the “flier,” scored a slightly higher 9. When used within their intended range, the little .32s will provide some good shooting.

Likewise, a couple of targets were shot at with the .38 that Lynn has. I can’t provide quite as complete a description of the loading process Lynn used for his loads, but he did tell me that he used 8 grains of Olde Eynsford 3Fg under a 158-grain bullet, using Lyman’s No. 358416. He selected that powder charge so the base of the bullet would basically rest on top of the powder, possibly with very light compression. I say that the bullet he used, while a good one, was not designed for the .38 S&W. That was actually the design for the .38 Colt Special, which used a flatnosed bullet, otherwise, the same weight as the standard bullet for the .38 S&W Special. Being heavier (by only 12 or 13 grains) than the standard .38 S&W bullet, the .38 Special bullets were seated into the case further than bullets designed for the .38 S&W, such as Lyman’s old No. 35864, which had only one lube groove, were used. That used up a small amount of room for powder.

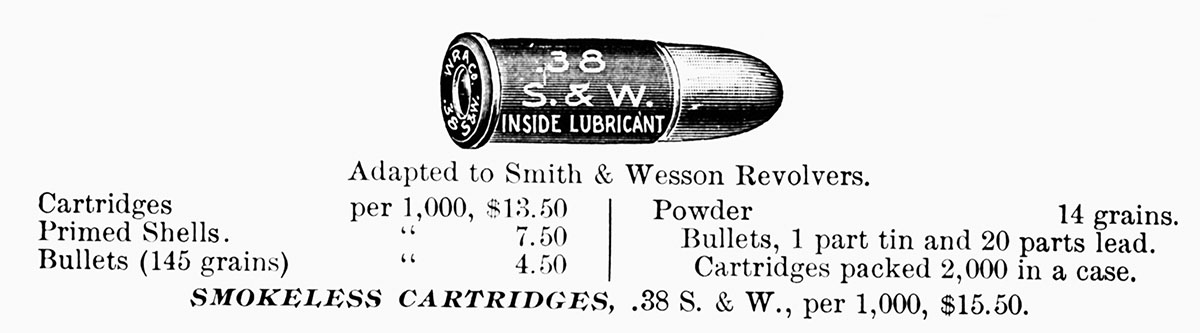

In the 1916 Winchester catalog, the .38 S&W is shown with a 145-grain bullet over 14 grains of black powder. The old Lyman Handbook #29 lists the .38 S&W with a “standard factory black powder” load of 12 grains of powder. Lynn’s loading in his .38, similar to my load in the .32, was close to half of the powder used in the old days.

Nonetheless, the .38 S&W loads with the 158-grain bullets over 8 grains of Olde Eynsford 3Fg powder shot quite nicely. Lynn’s group with his .38 is a bit wider than my group with the .32, but that can likely be explained by the fact that my gun had a nicer trigger pull than his. Besides, I certainly can’t criticize Lynn’s shooting because, as he’d quickly point out if he could interrupt here, his target’s score was one point higher than mine.

The .38 S&W black-powder loads were not chronographed. One reason for that is because we had no real reason to do so other than to satisfy our curiosity. Idle curiosity at that, because we have no needs for either our .32 or .38-caliber black-powder loads where power would have any bearing. If power is needed, we’ll both select other guns.

We’ll certainly be shooting our small Smith & Wesson revolvers some more as they are simply a lot of fun. While shooting them, we get to realize how certain things were in the old days and how the early centerfire cartridges helped pave the way for other/better cartridges yet to come. Yes, you might even say that shooting these old five-shot revolvers lets us be kids again.