The Uberti Model 1873

feature By: Mike Nesbitt | October, 18

The next one that came along is the purchased rifle seen in the photos. There was never even a suggestion of buyer’s remorse with this rifle. I’m more than glad enough to tell you all about it.

Let me also compliment the sights on this rifle, even though the rear barrel sight was promptly removed and a Lyman No. 2 tang sight installed; I’m referring to the fit of those sights to the barrel. On many of today’s copies of the old Western guns, the sights are poorly fit with air space between the sights and the gun’s barrel. That isn’t the case with this rifle; those sights are resting right on the barrel as they should be, and no extra light can be seen in or above the dovetails. Little things like the fitting of the sights are certainly tokens of good craftsmanship.

Both the front and rear sights are equipped with setscrews that need to be loosened before any windage adjustments are made and then tightened once the windage is set. The rear sight, of course, is adjustable for elevation as well.

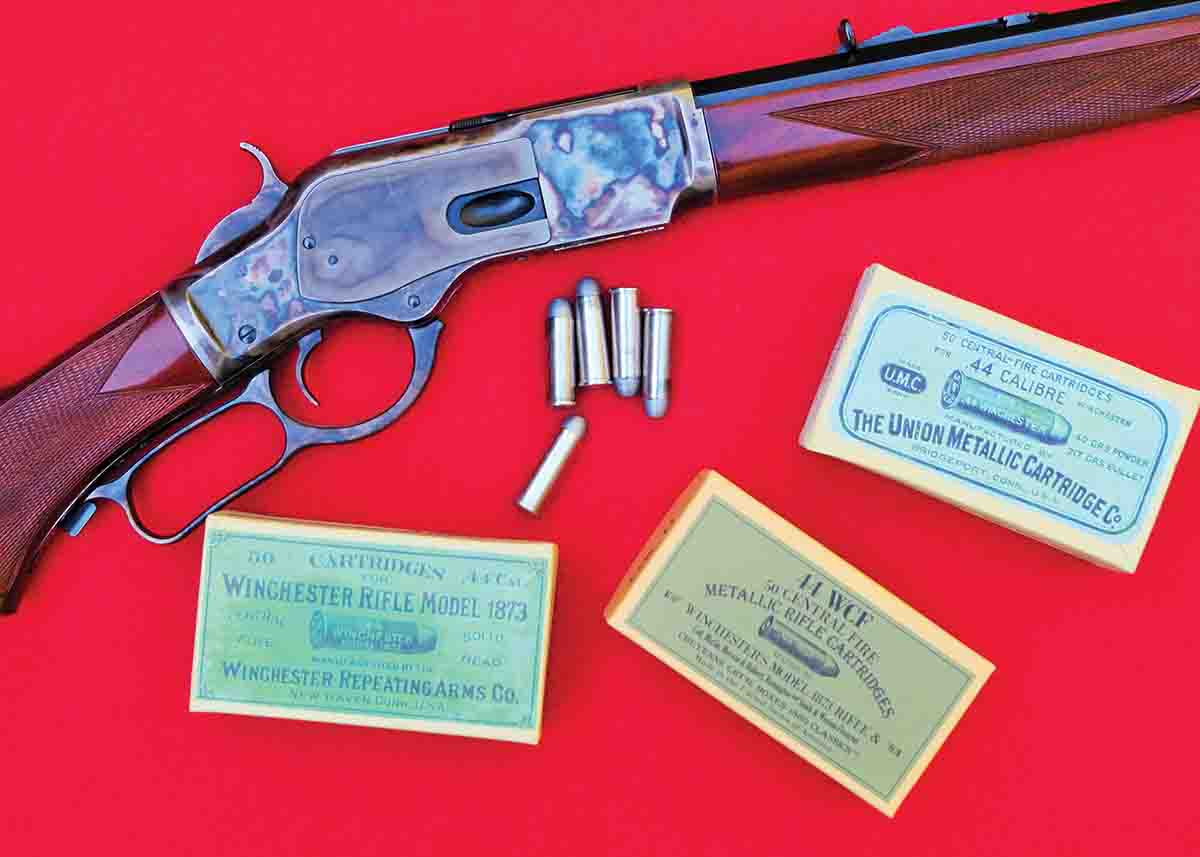

This rifle comes with an attractive color casehardening on the receiver, lever, trigger and hammer. On the original Winchester rifles, color casehardening was available at additional cost, so the casehardening can be considered just as authentic as it is attractive. The rest of the rifle’s steel features are nicely finished in a highly polished dark blue. Those pieces include the barrel, magazine tube, buttplate and nose cap, as well as the dust cover on top of the receiver.

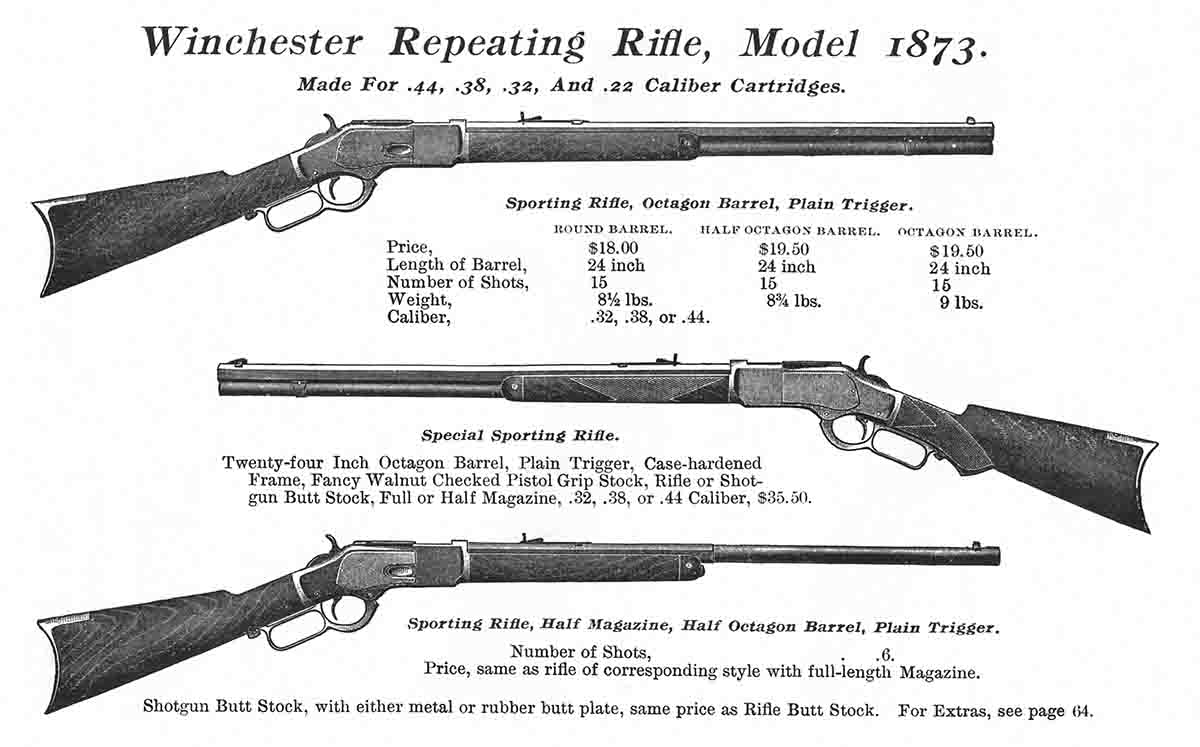

The original Winchester Model 1873 had a definite evolution, with small but noticeable changes during its 50-year span of manufacturing. This gun from Uberti represents one of the last versions, often called the “Third Model” because it has hidden hammer and trigger pivot screws, and the dust cover slides on an integral ramp on the top of the receiver. This rifle has a trigger block safety, which doesn’t allow the trigger to be pulled unless the lever is held tightly against the lower tang. In other words, the trigger block doesn’t allow the gun to be fired unless the action is completely closed. On the originals, the trigger block

My information about the Winchester Model 1873 rifles comes from The Winchester Handbook by George Madis in 1981. It states that the standard barrel length for a Model ’73 rifle was 24 inches, but barrels were produced from 14 to 36 inches. Half-round barrels were made in all lengths, but they are considered very rare. There might be an original that looks just like this rifle, but it would be expensive and hard to find. This fact makes me really appreciate this rifle’s availability and reasonable cost.

Most of the original Winchester ’73s with short magazines had the magazine tube ending just a tiny bit ahead of the forearm cap. If Winchester ever made a ’73 with the magazine extending another 3.5 inches beyond the forearm cap, I’m not aware of it. While I do appreciate authenticity with the copies of firearms that I favor, the fact that this rifle might not have an exact “grandparent” really doesn’t bother me.

Specifications for the barrels on the Uberti .44-40 rifles include: a rate of twist of one turn in 36 inches, a bore diameter of .4215 inch and a groove diameter of .429 inch. The rifling has a right-hand twist and six grooves. With that in mind, I never tried cast bullets that were sized to anything but .429 inch diameter.

The bullets from Lyman mould No. 427098 must be seated so the mouth of the case is crimped just over the forward bearing band in order to function through this rifle’s magazine. Before finding that out, a couple of loads were backed out of my rifle’s magazine through the loading gate because they were too long. That is a bit tricky, but it isn’t too hard to do, and is much easier than removing the magazine tube. So take note: Don’t use ammunition in a ’73 copy or original that is too long.

Almost all of my loads for this rifle used black powder, and with Olde Eynsford FFg powder this gun performed very well. My black powder loads used Starline nickel-plated cases for easy identification. A very good powder charge is 34.0 grains of Olde Eynsford FFg, although as much as 35 grains can be used in Starline cases.

It must be mentioned that in the old days, the .44-40 as well as many other cartridges, were loaded in “balloon-head” cases while modern brass is made in the “solid-head” configuration. The older balloon-head cases held more powder, which could contribute to higher velocities, even at the same pressures. This sporting rifle with its 24-inch barrel gave an average velocity for five shots of 1,230 fps. The loads fired over the chronograph had an extreme velocity spread of about 30 fps.

Another bullet used in the .44-40 was Accurate Molds’ No. 43-205C, that casts a .44 bullet designed to be used with black powder loads. That bullet and the other heavier versions like it are identified by their single, large grease groove. Both Lyman and Accurate bullets function through the action very well and print very nicely on paper. Both of those bullets can be seated with the same adjustments on the seating die.

There are several versions of the old 1873 Model made by Uberti, but I’m not really sure if this particular version with the short magazine and half-round barrel is still being offered. Things change, of course, so maybe it will be available again. I’m very pleased with this one, both in looks and performance, and that makes me even happier that I have it.

Shooting this Model 1873 is a simple reminder that the .44-40 was, and still is, a great black powder rifle cartridge. While the majority of my black powder rifle shooting will be done with a Sharps or a Rolling Block, the ’73 in .44-40 will generally be close at hand. For current information about the Model 1873 rifles and carbines, visit Uberti’s website uberti-usa.com.