The Wyoming Schuetzen Union's "Center Shot"

whatsnew By: Staff | February, 20

Once there was a time when openly airing the differing opinions of contentious personalities on the pages of sporting magazines was permitted and even encouraged. When the Savage .22 Hi-Power cartridge (and with it the smallbore, high-speed bullet concept) was unveiled in 1911, some wondered if it was actually the first rifle cartridge of its type. For answers, most riflemen trusted the authority and knowledge of Los Angeles writer E.C. Crossman, who at the time was published more frequently than Townsend Whelen. “Its parentage seems to be as much mystery-enshrouded as that of black powder,” Crossman wrote in October of 1911. He then made his case for the centerfire cartridge developed in 1909 by A.O. Niedner and Linwood Lewis of Dorchester, Massachusetts. The rifle was a rechambered Stevens Model 44-½ single shot and throated especially for base-banded bullets. The rifle and its ammunition received a fair bit of attention during the shooting season of 1909.

Charles Newton attempted to straighten out the record by reminding Arms and the Man readers of the series of .25 and .28 caliber “special cartridges” he had formed by necking down larger existing cases. Included in this line was a .22 caliber shell made by tapering a .25-25 Stevens case to hold a .22 caliber bullet. In attendance at the Buffalo, N.Y. range, while Newton was working out the cartridge’s loads was John Taylor Humphrey, then editor of Shooting and Fishing magazine. Humphrey printed Newton’s results (and his own prediction of the future) in a November 1906 issue of his magazine.

A communication from “Trim Nat,” the familiar pen name of Thomas Martin (skilled rifleman, talented sight manufacturer and a “fixture” at Walnut Hill) was also printed that November. Martin was in a position to know the facts and was able to refresh the memory of the current readership concerning a local’s innovation, which had, in 1894, captured the rifleman’s imagination. Martin proceeded to establish his familiarity with the invention, as well as, his close acquaintance with the inventor who had made a specialty of providing rifles chambered for a proprietary smallbore cartridge that may have filled a recognized need. It was a .22 caliber, burning 20 grains of black powder and delivering nearly 2,000 feet per second; an eye-opening development for the mid-1890s. Thomas Martin pounded on the table and authoritatively declared: “Here we have the first inception of a real high power .22 cartridge,” and “that this cartridge was the first real practical .22 High Power cartridge actually made and put on the market seems to be without a doubt.” Martin delivered his concluding salute: “Hats off, gentlemen, to Harwood.”

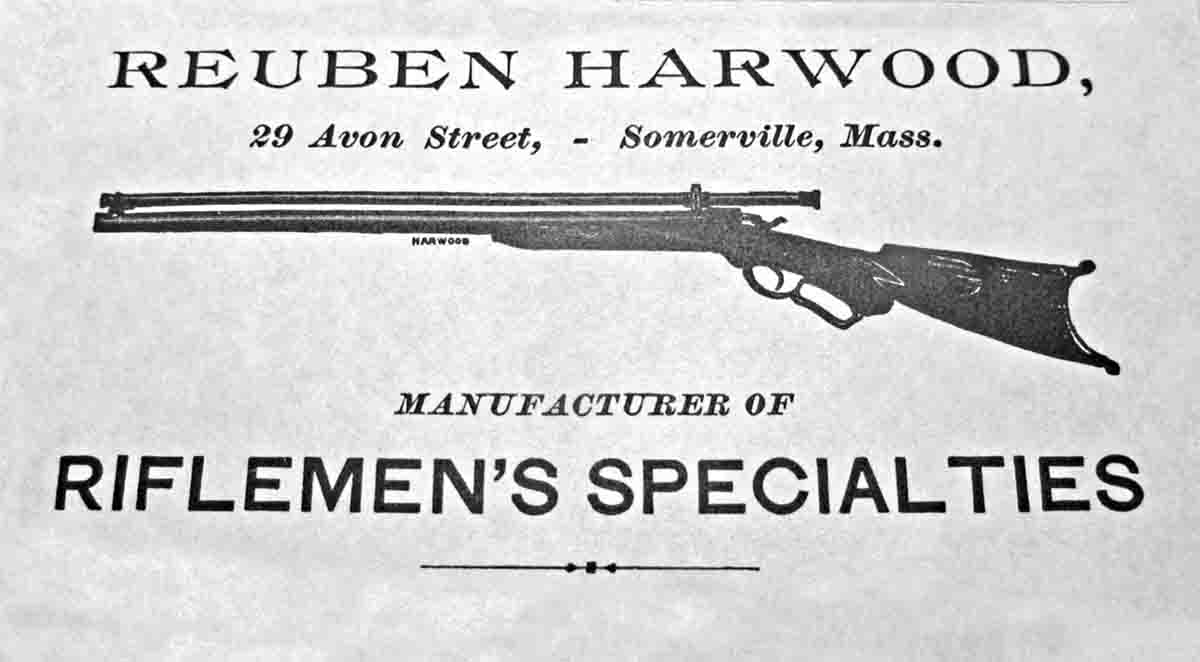

Reuben Harwood was once a prominent personality who catered to the many serious riflemen in the Boston area, that great center of eastern rifle activity. It’s regrettable that Harwood’s milestone achievement came to be so forgotten, even for those writers of the next generation who were regarded as the best informed.

Reuben Harwood was a ninth generation descendent of Henry Harwood, who sailed from England in 1630, and settled in Charleston, Massachusetts. Reuben was born on April 3, 1849. After making the discovery that the life of a traveling salesman wasn’t his calling, he trained as a machinist. At age 34, he opened a shop at 33 Avon Street in Somerville, Massachusetts. As many naturally exacting, mechanically-gifted young men seem to be inclined, Reuben developed a captivation with rifles, the shooting of rifles, and directing their projectiles with precision. He surrounded himself with like-minded souls and became familiar with his fellow riflemen’s wants, needs, and aspirations. It naturally followed that Harwood’s machinist talents were turned to general gunsmithing. Apart from this, he attached sights and telescope mounts. He fitted and chambered barrels and gave worn or rusted tubes a new lease on life by re-boring and re-rifling them to a larger size. He could, and did build muzzleloading rifles from scratch, and this was well into the days of the breechloader.

In the marksmanship-mad Boston area, that great hub of eastern “rifledom” and home of the celebrated Walnut Hill range, there was a vacant niche; a demand for the combination of a mechanic who knew rifles and a purveyor who knew riflemen. In 1888, Reuben Harwood moved his operation to a roomier location a few doors down at 29 Avon Street and opened a simple gun repair shop and sales room.

His own range frequency and reputation, as an authority on rifle matters, accelerated his shop’s establishment among Boston’s rifle cranks. It behooved Harwood to know his customers and understand their wants and needs if he was to be successful in serving them. He embraced this philosophy and came to enjoy certain significance among the region’s riflemen. He relished this deserved status.

Harwood was well-known for his personal guidance to those green at the sport. His services were highly recommended “to those who are in doubt about the proper arms for special work.” The budding shooter, left to his own devices in choosing equipment, risked either the fueled enthusiasm of success or an interest-ending disillusionment upon viewing his first targets. Harwood’s shop made a specialty of furnishing fine range-ready rifles, selected, sighted, and adjusted by the expert rifleman himself before delivery to the customer.

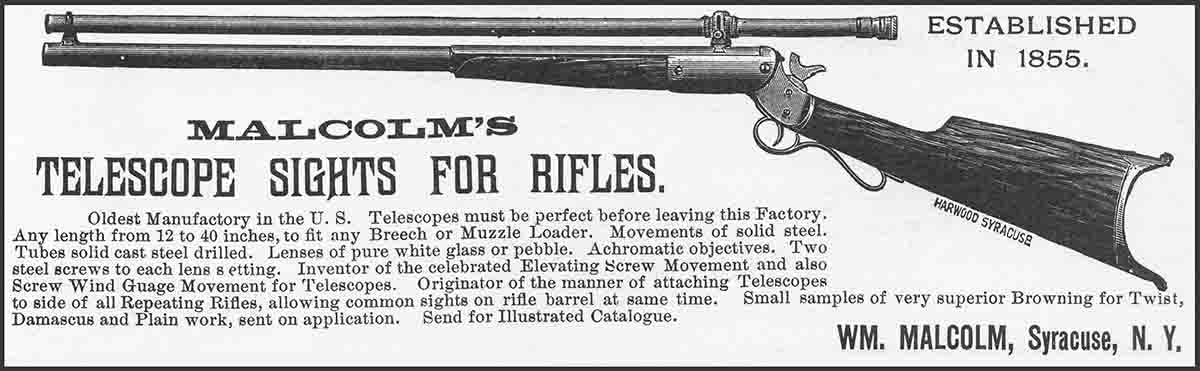

Reuben Harwood supported his fellow rifle enthusiast with a useful and necessary line of shooting products and accessories. He handled and stocked the rifles of Maynard and Stevens, as well as being an agent for the “best on earth” Mogg telescopic sights. He made sight discs and jointed brass cleaning rods and sold “Fellows” cleaning tips. Harwood made shell scrapers and bullet seaters. For those who couldn’t mould proper bullets, he would cast them to order.

In 1900, Harwood designed and manufactured a bullet lubricating pump, patterned after Harry Pope’s. Harwood would furnish interchangeable dies to lubricate different diameters. Many of Harwood’s lube pumps found their way into the shooter’s kits at Walnut Hill. At the same time, he introduced a proprietary Alkaline Bullet Lubricant of his own concoction that found favor with some. In 1890, a stick sold for a quarter.

That same year, when the .25 Stevens rimfire cartridge was introduced and became the current craze, Harwood’s Shooting and Fishing ads informed the shooter that his shop was ready with the goods – rifles and cartridges in ample supply. Just as importantly, Harwood was one of those hard-to-find kindred souls with the willingness and know-how to offer the service of “rifle cranks special notions worked out.”

Harwood was known around Walnut Hill as an innovator and experimenter, and in this regard, he had plenty of company. Club members, in the main, were serious riflemen, many of whom were inclined to delve into the science of the game. Several members of the Walnut Hill crowd were progressively minded, creative people. Among them were inventors, patent holders, skilled mechanics, and manufacturers of shooting instruments and accessories. The club grounds provided a gathering place and the atmosphere for mutual inspiration, challenge, and encouragement. Harwood fit in well among the like-minded, august company and belonged there. Sight manufacturer Thomas Martin, who hid behind the nom de plume “Trim Nat,” once reflected on the palmy heydays of the club when he and cohort Harwood often came together at a firing point to tinker and experiment.

A side aspect of Harwood’s involvement in his trade and passion for riflery was his role as columnist. He contributed to journals whose focus was rifles and shooting, notably Forest and Stream and Shooting and Fishing. As a personality, Harwood connected with the readership and drew a loyal body of followers. He had a flair for communication; his homey, readable prose made his audience feel competently guided, as his experience and authority were convincingly imparted.

It was a custom of the 1880s, for magazine contributors to write under a pen name. Harwood hid transparently behind “Iron Ramrod.” For his own reasons, he sometimes used “Aberdeen,” and when he was feeling particularly evasive, Harwood wrote as “Ben Wood.” A number of Walnut Hill competitors used a nom de plume as their shooting name, and this alias appeared on the rosters. He and his compatriots, playfully perhaps, manipulated their first and last names to follow the same quirky form. It is thought that on the range, Reuben Harwood was aka “Ben Wood.”

Harwood’s byline is first noticed in late 1881, when he filed a Forest and Stream report about a .32 rimfire rifle he’d converted to centerfire, and the use of #1 buckshot in its reloadable ammunition. He became better known for his primary expertise as the authority on the sport of small-game shooting and the rifles and cartridges for this activity. This was the staple pursuit of the typical urban eastern rifleman who lacked the interest or means to join an organized rifle club. Back then, rabbits and squirrels and sparrows were plinked wherever they were found. Songbirds were considered fair game, and ducks and geese were sniped on the water year ’round.

In 1888 and 1889, “Iron Ramrod” wrote a seven-installment Forest and Stream series of wordy essays evaluating the various rimfire .22 calibers. The pip-squeaking .22 BB and CB caps were fine when shot in residential parlors, but for field use they were “utterly useless.” He wrote that the .22 Short had usefulness beyond the indoor gallery, and that was the general indiscriminate practice of shooting random birds “around town and city back yards.” Harwood went through a lot of words evaluating the .22 Long before rendering his terse opinion. Harwood wrote, “Don’t use the .22 Long,” and moved on.

At first, he was a fan of the .22 Long Rifle shell, but over time he came to recognize its shortcomings, not the least of which was its acute sensibility to wind. It made a fine 200-yard target cartridge, he thought, but the trajectory was hopelessly high. He also considered the Long Rifle to be a “failure in the woods,” but its greatest fault was that the case was not reloadable. Harwood held out some hope for the .22 Extra Long rimfire, but its power was very little better than the Long Rifle. Woeful inaccuracy was its fatal flaw.

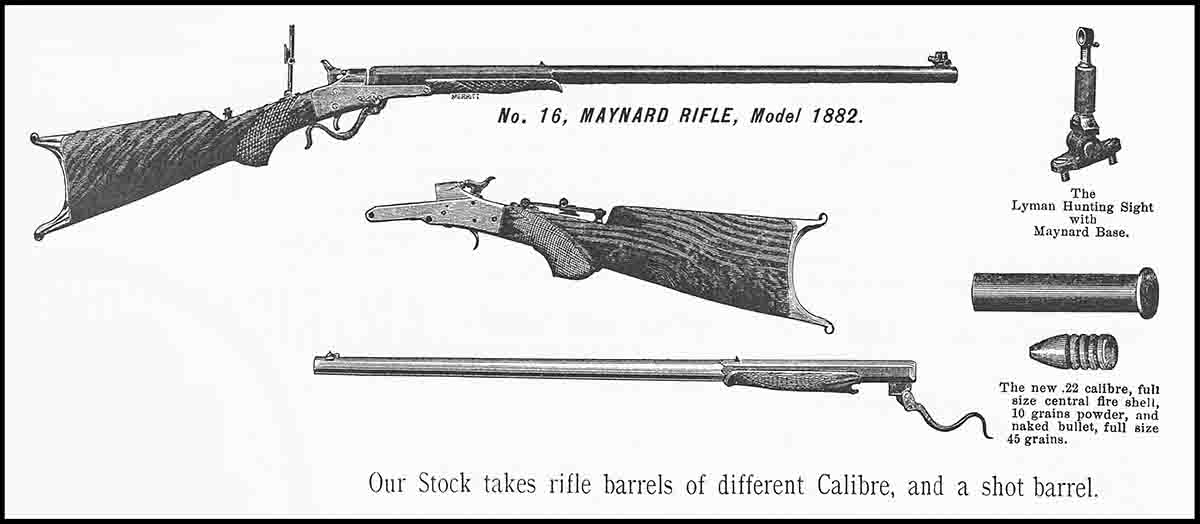

By 1888, Harwood advanced that a better choice for a small-game rifle could be a .22 centerfire. Based on his own experience, he championed the .22 Maynard, also called the .22 Extra Long Center Fire, or the .22-10-45, .22-10, .22-10-45 Maynard and .22-10-45 CF. When “Iron Ramrod” specified “.22 CF, 10 grs. Powder, 45 grs. Lead,” his followers knew the cartridge referenced. Its 45-grain bullet poked along at about 1,100 fps, marginally better than the 1890 loading of the .22 Long Rifle, but enough to make a bit of a difference.

Harwood knew that he was forced to occasionally explain principles difficult to comprehend for some Forest and Stream readers in understandable terms. The .22 Maynard outshined the Long Rifle, he tried to explain, simply because it had a “great deal more ‘get there’ to it.”

Besides the Massachusetts Arms Company (Maynard), the Ballard, Bullard, Wesson, and Stevens Arms Makers chambered their single shots for the Maynard .22. Harwood’s rifle was a Maynard Model of ’82, two-barrel set. One barrel was chambered for .22 Short and the other in .22 Maynard. “Far ahead of the .22 Long Rifle” he pronounced the .22 Center Fire Maynard.

In 1888, the “Big Red W” (Winchester) shipped to its natural first choice of influential product evaluators a modern rifle in an up-to-date chambering. Reuben Harwood received the Winchester Single Shot chambered for the new .22 Winchester Center Fire, along with a short stack of targets, two boxes of cartridges, and the request to test the gun for accuracy and publish the results.

“Iron Ramrod” was able to report that not only was the Winchester round fully as accurate as the finest .22 Long Rifle, it was also the “strongest shooting.” Factory cartridges were filled with 13 grains of 2Fg black powder and capped with a 45-grain lead bullet. Muzzle velocity was advertised as 1,500 feet per second. The bullet of the speedy .22-15-45 reached the 100-yard target more quickly and its trajectory at that distance was half that of the .22 Long Rifle. The .22 WCF didn’t lose its field effectiveness at 100 yards as did the .22 Long Rifle, and was noticeably less wind sensitive. That the bullet was inside lubricated, and the shell was fully reloadable were other points regarded as advantages. It was easily seen that Harwood was a fan of Winchester’s new smallbore black-powder centerfire.

Harwood continued to champion the .22 W.C.F., and late in 1890, he still considered that it was “by far the best yet produced.” He added, as if foreshadowing, “but there is still room for improvement, the writer has no doubt.” After a noticeably long lapse in Iron Ramrod’s welcomed Forest and Stream contributions, one reader, who presumably represented the mainstream, finally quizzed the editor in 1892, “Why can’t we have something from his interesting pen again?”

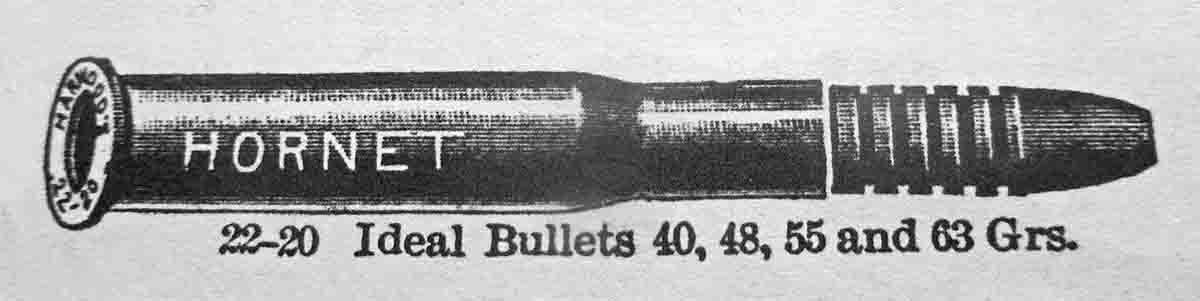

With nothing in the way of a leak or advance notice, Shooting and Fishing carried the announcement of a new rifle cartridge in its March 22, 1894 issue. An accompanying illustration showed a slightly shouldered, bottle-shaped case with an inordinately narrow neck, grasping a disproportionately slim bullet. This fresh look was a decided departure from the conventional straight-walled or tapered cartridge case. It was a .22 caliber cartridge that carried the familiar name of its designer Reuben Harwood, linked with the catchy moniker of “Hornet.” Its other designation, “.22-20-55” specified its caliber, bullet weight, and capacity in grains of black powder, a striking increase over the 15-grain charge of the .22 Winchester Centerfire cartridge.

Getting ahead of himself perhaps, the article’s writer ventured his private prediction that the .22-20-55 would “become one of the most popular centerfire shells now made.” He also let slip the rumor that Stevens may become involved in producing complete Hornet rifles at its factory. At the same time, the public was made aware that Harwood stood ready to take orders for complete single shot Hornet rifles with his barrels. Harwood would also recut worn .22 rimfire barrels to .23 caliber for use with un-sized .230” bullets. At a cost of $1, a .22 Maynard or .22 WCF could be rechambered to .22-20.

It is a matter of record that A.C. Gould, who at the time was Editor of Shooting and Fishing, christened Harwood’s new cartridge. Gould was on hand at Walnut Hill for preliminary .22-20 firing, and the buzz of the little bullet reminded him of the drone of that six-legged stinger. The name stuck and it was the “Harwood Hornet” thereafter.

Harwood chose to base his Hornet on the .25-20 single shot case developed by J. Francis Rabbeth in 1882. It was suitably spacious and had the advantage of a durable solid head construction. Harwood’s placement of the shoulder was adjusted to hold the targeted 20 grains of powder, leaving a neck long enough to secure bullets longer than standard.

Harwood would furnish, die-formed from the parent case, .22-20 Hornet shells. “Trim Nat” mentioned that Harwood would also provide swages, shell reducers to form the neck, as well as loaded cartridges. A nickel sent to his shop brought a sample case with bullet by return mail. John Barlow of Ideal Manufacturing supplied his standard #4 tong tool with integral mold, together with his #3 Special without mold. These were marked either “.22-20” or “.22 Harwood.” The 1895 Ideal Handbook shows a cut of the Hornet case clearly head-stamped “Harwood .22-20,” which may have given rise to a rumor that one of the cartridge plants, allegedly Union Metallic Cartridge Co., was going to produce cases and possibly ammunition. Not everyone handloaded, and prospective rifle purchasers wanted assurance of a steady supply of cartridges. That the whole of the current American cartridge collecting community has never sighted a head-stamped .22-20 Harwood specimen leaves this rumor unsupported.

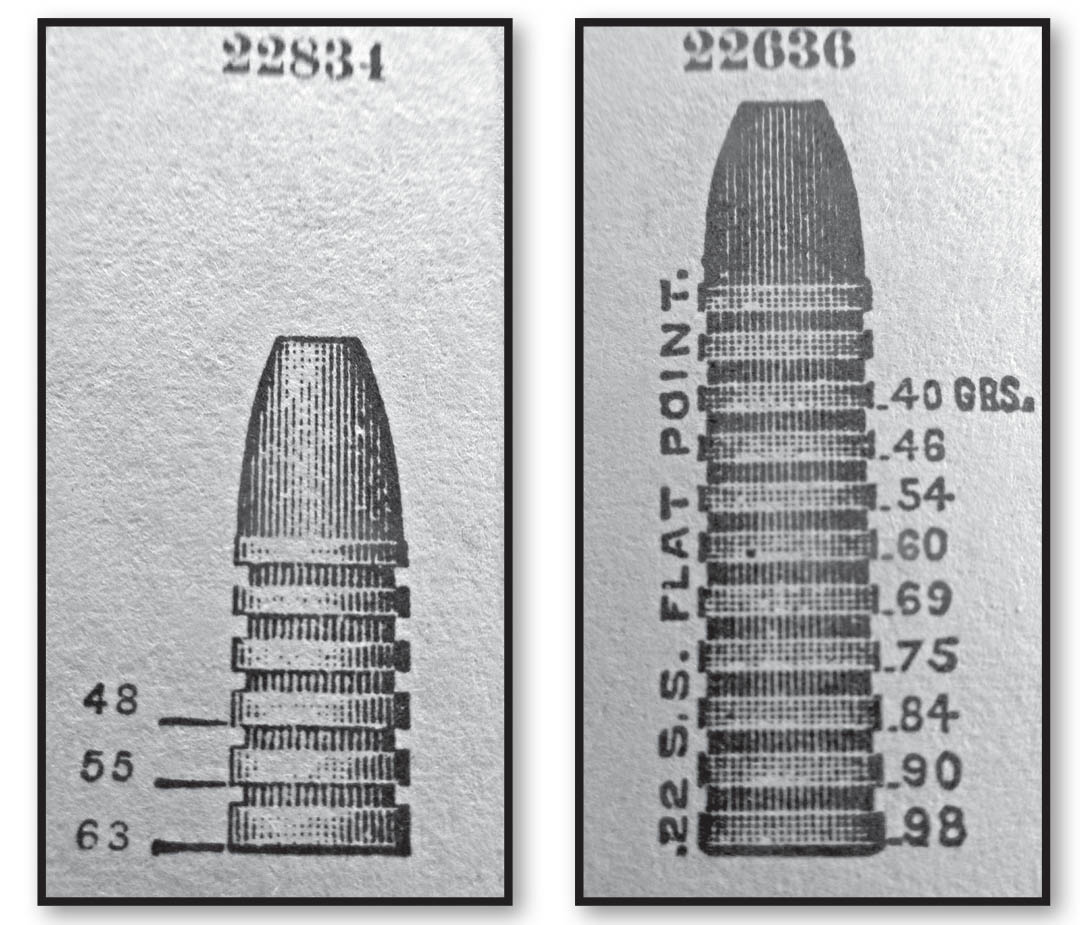

The cartridge illustration in the Ideal wish book suggests that Harwood was specifying a certain bullet available in weights of 40, 48, 55, and 63 grains. This range of weights squares with the Ideal #22834. It was also the standard bullet for the .22 WCF It was the 55-grain version that gave the Hornet its .22-20-55 designation. Those who didn’t cast bullets could get them from Harwood’s. Alternatively, using the .22 Long Rifle bullets that were sold as a handloading component then, was Harwood’s suggestion.

Reloading the .22-20 shell was simple and straightforward. The earliest Ideal Handbooks suggested 20 grains of black powder and a pure lead bullet. Shooters couldn’t go wrong with the Harwood-recommended load of 15-to-20 grains of black powder over a four-to-five grain priming charge of “nitro,” which provided a certain, uniform ignition and reduced fouling. Evidently, any of the few available nitro powders would do. Harwood used a fired .22 Long Rifle shell to measure the smokeless. Seat the almost universally used 55-grain bullet conventionally and don’t crimp the shell.

Harwood’s preferred rifling pitch was thought to have been one in 12 inches, which had stabilized the 63-grain bullet after the standard 14-inch twist had failed to do so. Modifying a .22 rimfire barrel to the Hornet was generally something of a compromise. Harwood advised prospective customers that a suitable Maynard or Stevens .22 Long Rifle barrel could be successfully altered, though the standard pitch was one in 16. Owners of a centerfire .22-7-45 (.22 Extra Long) with a standard 1:14 twist already had the ideal platform for updating to the new Hornet cartridge.

These days, riflemen insist on knowing the muzzle velocity of their cartridges down to the foot second, but our 1890s black powder counterpart wasn’t overly concerned. Data from Ned Roberts’ personal correspondence with Harwood, from the years 1894 to 1895, provides some probably reliable Hornet velocities. Harwood claimed 1,900 fps with a 48-grain type-metal bullet with a smokeless-primed black powder load; 1,750 fps was supposed with a 55-grain bullet motivated by the same charge. A load of DuPont #2 Rifle Smokeless, primed with 2Fg Semi-Smokeless, blew the 48-grain bullet out of the barrel at nearly 2,000 fps. Whether these numbers were guessed at or actually measured is uncertain. People with the exposure and influence that Reuben Harwood enjoyed, could often persuade a powder company to determine actual velocities over the LeBoulenge chronograph each plant was equipped with. It was said that the United States Cartridge Company in nearby Lowell, Massachusetts was particularly accommodating to certain cranks. Charles Newton and A.O. Niedner often took advantage of their graciousness.

Unless our ancestral gun crank was a Schuetzen rifleman, he had no obsession with minute of angle accuracy from a common rifle, as the Harwood Hornet more or less qualified. Hornet group sizes of any sort were seldom recorded but one man reported he had placed 10 shots into four inches at 100 yards, six of them spanning but an inch-and-a-half. Another put 10 shots into a two-inch circle at 50 yards, which is probably representative accuracy, all things considered.

The Hornet was the original flat shooter. One man summarized succinctly: “Just hold a little high when you think it (the target) is over a hundred yards, about three quarters of an inch above center at 150 yards.”

Late in 1894, William V. Lowe of Fitchburg, Massachusetts, a prominent rifleman and rifle maker, circulated a leaflet announcing his intention to specialize in quick twist, smallbore Express target rifles. Further, he revealed that he was prepared to furnish and fit .22 caliber barrels with a 12-inch twist to stabilize a 75-grain bullet (the Ideal 22636 could be had in this weight). Lowe unabashedly disclosed his chosen shell to be the Hornet case, holding 20 grains of powder and the long bullet. Lowe had effectively appropriated Harwood’s entire original concept and design, putting his paltry 20 grains of extra lead “spin” on it and marketed the notion as his own. While Lowe’s tactic smacked of thievery, the point was moot. There were few takers.

Harwood never indicated that bringing the Hornet into being was anything other than a solitary venture. John Taylor Humphrey waited until 1906, before bursting into print with this unexpected disclosure in Shooting and Fishing (where he held the position of editor): “…over ten years ago, with Reuben Harwood…we developed the .22-20 Hornet. We used a .25-20 shell reduced at the muzzle to .22. A long series of experiments resulted in the conclusion that with black powder, 22 grains would give un-accountables at times, despite the greatest possible care in loading, etc. …” Humphrey’s claim may or may not have some foundation. In the mid-1890s, he was a frequenter of the Walnut Hill range, as was Harwood. The name of J.T. Humphrey was commonly seen on that era’s competitor’s rosters.

Directly from the pen of a Pennsylvania hunter (with no reason to mislead) and into a late 1890s Forest and Stream column, we have this nugget for every scoffer. He maintained that he had “obtained two Stevens Ideal rifles factory chambered for the Hornet.”

On the whole, Harwood’s .22-20 curiosity couldn’t overcome the public’s indifference and suspicion, and the common impassiveness to his smallbore, high-speed concept. The people were underwhelmed. The Hornet fit perfectly into an ultra-specialized niche that didn’t really need filling. In the minds of many, the Hornet case was fundamentally flawed, and the wisdom of the day maintained that bottlenecked cases were very prone to breakage and separation. Another fatal drawback to owning a Hornet was the absence of commercial ammunition. But a small percentage of those who regarded themselves as riflemen handloaded, and the rest were dependent on a single source of cartridges that was one man’s part-time output. Apart from a scattered handful of full-blown rifle cranks, the market Harwood might have imagined just didn’t exist.

The Harwood Hornet was very seldom mentioned in the rifleman’s press. That the Hornet could have been better promoted would be a colossal understatement. The legacy of Reuben Harwood’s .22-20 was to be remembered as the most forgettable rifle cartridge in the history of arms and ammunition.

Everyone has a story, including Reuben Harwood. At some point before 1900, he appears to have dropped out of the gun business. He then turned his mechanical skills to clock and optical equipment repair. By then he’d buried two wives and two of seven children. He made Kate Hendrix bride number three in 1905. In 1910, Harwood was living in Springfield, Massachusetts, employed at an automobile factory as a “scraper.”

Midway between Savages early 1911 announcement of plans to market a speedy High Power repeater and that autumn’s Arms and The Man bout of misidentifying the concept’s originator, was E.C. Crossman’s field test of the pre-production “Imp” in California. The magazines kept the itchy public updated, but neglected to mention on July 22, 1911, the death of Reuben Harwood, and not a word about “Iron Ramrod,” who once was such an influential presence.

Still, some Harwood Hornet owners held their rifles dear, and made their fond attachment well-known. Harvey Donaldson once wrote of a chance encounter in the Vermont squirrel woods that is the stuff of a far-gone gun nut’s fantasy. Donaldson happened on an aging fellow hunter carrying a well-used, Malcom scope-sighted Maynard rifle chambered in .22-20 Hornet. The two lingered and talked of things in common before eventually moving on. Money couldn’t buy it; Harvey tried.

In a 1916 issue of Outers Book, we find an old timer’s letter to the editor of the magazine’s gun department, reflecting on his younger years when he was a .22 Harwood Hornet owner and operator. Identified by his signed initials “C.S.K.,” he had befriended a Steven’s Ideal with a 15-power telescope. With it he’d shot “plenty of squirrels, woodchucks, hawks, ducks, and tin cans.” Of his relationship with the inanimate rifle he was moved to say, “The shooting I did with this rifle and the .22 Hornet cartridge in the ‘90s was the most pleasant experience of my life with the gun. The taste lingers.” We all deserve a rifle like that.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)