The Wyoming Schuetzen Union’s “Center Shot”

Reunion of a Rifleman

column By: Jim Foral | March, 22

With these words, Col. Leslie Combs Bruce began his address to a roomful of his invited guests. This gathering on December 14, 1901, in a private dining room at Manhattan’s plush Murray Hill Hotel was called for what the congregation had in common.

Many represented the “Old Guard” of New York’s Amateur Rifle Club that had so famously competed in the great international rifle matches at the Creedmoor Rifle Range in the 1870s, and made the U.S. the recognized champions of the rifle world. In their day, they were revered as national celebrities before the years turned them into greying, balding and paunchy, though yet distinguished older men. Bruce was a long-standing fixture on the regional long-range rifle scene. He had won a spot on the 1875 and 1877 Creedmoor teams and was admired in shooting circles for his self-assured, “take charge” presence.

George W. Yale and L.L. Hepburn, rifle builders both, and firing members of the 1874 team were seen seated together and catching up. H.S. Jewell of the 1877 team sat with Isaac L. Allen who shot on the U.S. squad at Creedmoor in the centennial year (1876). John Bodine, a former colonel with the New York militia and who still bore the nickname “Old Reliable” for very good reason, was also in the crowd.

William Hayes of Newark, tabled with fellow champion and contemporary Frank Hyde, now three score and 10 years and still shooting. That fall, he won the All-Comers Match at Sea Girt with a .30-40 Remington-Lee match rifle. Old men L.M. Ballard, who went to Ireland in 1875, as a reserve, and H.I. Clark of New York, veteran of the Creedmoor shoot of 1875, broke off on their own.

The years that aged the group, took some of them too. L. Weber, one of the eight men on the American team for the 1876 International Match at Creedmoor and his teammate Ransome Rathbone were both gone now. Dead too, was General Thomas S. Dakin, standout of the original Amateur Rifle Club’s 1874 team. Colorful personality Major Henry Fulton, civil engineer, Civil War veteran and Andersonville prison survivor, had committed to attend the reunion but fell over dead a short time before his departure from Colorado.

Birds of a feather sat together. Gen. Bird Spencer, president of the newly-revived National Rifle Association (NRA) and its secretary, Albert Jones, needed to be present, and were. Arthur C. Gould, widely known as a spokesperson for the furtherance of rifle shooting was with them. Former NRA Secretary P. Schernerhorn was one of that organization’s Creedmoor-era survivors on hand.

James Conlin, who owned a popular indoor shooting gallery on Broadway Boulevard in New York, was also asked to attend. Conlin’s Gallery was a gathering place for the urban rifleman and this person’s primary source of rifle-related scuttlebutt. Crack journalist S. E. Whitley, with the old

New York World headed the indispensable press corps to cover the night’s event and assure themselves of both a free dinner and an earful of unsolicited information. Noticeably out of place in a field of civilians was the uniform of army officer and honored guest, Captain Zalinky, one of the few military men to recognize the value of the NRA and its mission. This mood was about to change.

Bruce opened a round of after-dinner speaking by sharing his disappointment after watching the distressing spectacle of a Canadian rifle team carry away the Palma trophy that summer. The Canucks had decisively beaten the best team America could assemble, and did it on their own Sea Girt range. A month later, he was in the crowd that watched as the Ulster Rifle Club of Ireland met a contingent of Jerseymen at long range with military rifles, and trounced them soundly.

Harking back to the palmy days at the Creedmoor range that everyone present remembered so fondly and proudly, Bruce stated his determination to again put American distinction at the top of the list – where it had been in the 1870s. To reverse the current momentum, Bruce declared that he saw the need of the old riflemen assembled to give of their time, brains, and resources. All of the invited present in the room possessed beneficial skills, leadership capabilities, and clout that could play an essential part in Bruce’s planned endeavor.

Gildersleeve and others spoke in a nostalgic strain that provoked thoughts and hope of a reemergence of the 1,000-yard domination and to future victories of the soon-to-be heroes and their heroics. Spencer addressed the group with the promise of the Sea Girt ranges and facilities at their full disposal. Another well-intentioned veteran urged a scientific study and analysis to gain the necessary knowledge of extreme range and its effects on the high-speed, small-bore bullets coming into fashion. New obstacles and unconsidered variables awaited them. They fully understood the .44 and .45 caliber black-powder cartridges of their time, but this was uncharted territory for those who hadn’t kept up, and it behooved them to understand.

Many of those not able to attend the event submitted valuable suggestions in writing. One proposal was to form a committee to compare the various positive recommendations, and to sort through their beneficial points. Also having merit, Bruce thought, was the consideration of forming a unified body of long-range riflemen to succeed or supplant the Amateur Rifle Club. The wheels started haltingly and the Old Guard applied grease wherever they could. The public, already stirred by the recent Spanish-American and the Boer Wars, was becoming more and more enthused and increasingly receptive. Long-range marksmanship of any sort, thankfully, for the time being, was an easy sell. Generally, results wrought by the efforts of the 1870s veterans were not broadcast or crowed about, and seemed to be quietly credited to the National Rifle Association, which was long overdue for favorable ink.

Those hopeful of a rejuvenation of the still struggling NRA and the resurrection of long-range competition had two like-minded guiding spirits committed to the cause. Each man had a long history of service and successfully getting things done. In 1871, Spencer was among the incorporators of the NRA. Later, he was appointed to the post of Inspector General of Rifle Practice of the New Jersey National Guard. In 1884, Brigadier General Spencer had secured a parcel of New Jersey coast land to develop as a rifle range/National Guard camp. The famous Sea Girt range was then built in stages. By 1891, interstate matches were being held, and in 1897 Army teams joined in a competition with the states. For several years, Spencer kept the impotent NRA’s head above water financially by conducting the annual matches of the New Jersey State Rifle Association at Sea Girt. Sea Girt was the man’s passion and his legacy. Fittingly, he died in its clubhouse on July 28, 1931.

Like Spencer, Wingate was among the founders of the NRA, and had a particular interest and talent for marksmanship training. He was instrumental in getting a patch of overgrown New York marshland transformed into the proud home range of the NRA. Wingate was also the president of the Amateur Rifle Club during the peak of its glory days. He did a stint as Inspector General of Rifle Practice for New York. Several setbacks caused the NRA to deed the Creedmoor range to the state of New York in 1890. The grand organization settled into a state of non-vital dormancy for the next eight years. Wingate served as the NRA’s vice-president from 1877 to 1885, and its president from 1886 to 1900. Spencer succeeded him as president for the next six years.

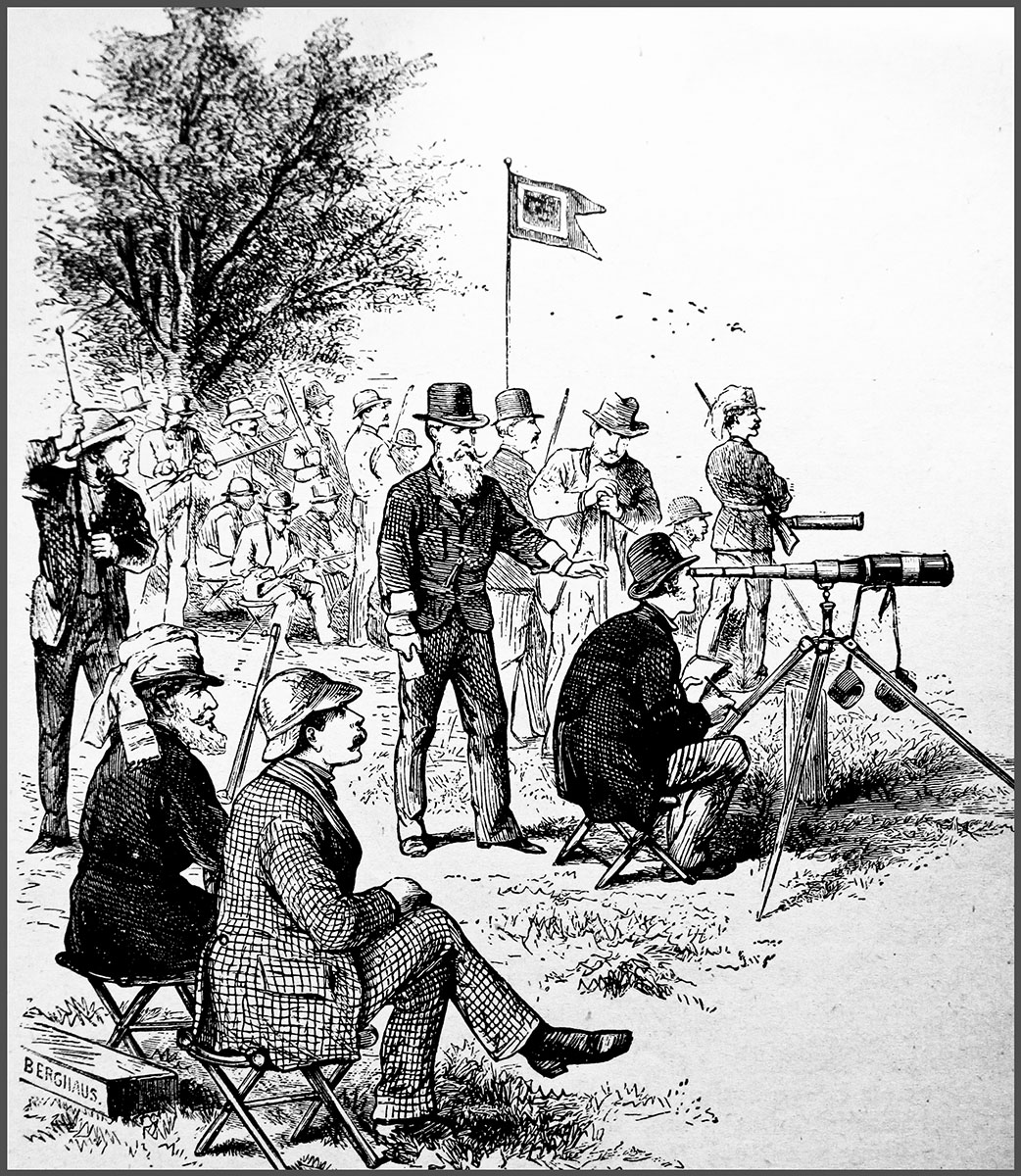

The string of international matches with American participation during the heyday of Creedmoor was actually a short, though remarkable one. The inaugural meet between the American team and the visitors from Ireland was sponsored by a fledgling NRA and shot on their grounds in September 1874. The outcome was decided by the last shot fired through Bodine’s Remington. With a cut and bleeding firing hand, he squeezed off the winning shot. A spirited uproar let loose from the crowd numbering 8,000 voices, and rifle shooting was cemented as an 1870s spectator sport.

The return match of 1875 was held at the Dollymount range near Dublin, with the U.S. again the winner. America hosted the 1876 matches at their Creedmoor range. Top-quality teams from Ireland, Scotland, Australia and Canada provided the competition and worldwide attention to the event. The U.S. team took place very decisively. Gluttons for punishment, teams from England, Ireland and Scotland crossed the Atlantic for another humbling at Creedmoor in 1877. No foreign rifle team accepted the American challenge for an 1878 match.

An 1880 U.S./Ireland matchup was held at Dollymount. An unheard of posting of 221 bullseyes with 41 centers in 270 shots – without a miss – put the Americans on top of the world again. The last International match was marked in 1880, using single-shot match rifles.

Generally, there was a noticeable clamoring for the revival of New York’s Amateur Rifle Club or an organization patterned after it. Shooting and Fishing magazine applauded this idea of reorganization. After the recent defeats, that paper editorialized: “There has aroused a new interest in rifle shooting, particularly so among the veteran rifle shots, who, it was supposed, had laid aside their rifles for good and all.” This, together with other indicators, could be interpreted as resurgence in the interest of shooting at the time.

In the fall of 1901, a point was reached that the recovery of abandoned and misplaced trophies owned by the NRA became important as part of the overall plan for the future. In October, the historic Leech Cup was reported to have been “unearthed” from the vaults of Tiffany & Co. by a “well-known rifleman.” Years before, Wingate had the foresight to rescue it from the NRA storehouse, lest it fall into a melting pot somewhere. He then delivered it to the New York jeweler for a preservation of unknown duration. Wingate paid the storage fees from his own pocket and asked permission to present it to the revitalized NRA.

Later that month, it was proposed that the Amateur Rifle Club, never officially disbanded, be revived and the Leech Cup be again contested for annually, the original directive of Major Leech, its donor. Another step in the right direction, it was felt, that by consolidating the old Amateur Rifle Club with the very active Manhattan Rifle and Revolver Club would give the union the greater weight in numbers.

Bruce, instigator for change and the “Pied Piper” of the movement, practiced what he preached. Bruce, together with Hyde, served as mentors and acted as shooting masters, giving old-school coaching to the enthusiastic young shooters eager to master the rifle. The Bruce/Hyde alliance also busied itself with trying to isolate the reasons the government Krag bullet tumbled past 800 yards. A band of self-styled National Guard diagnosticians – notably Walter Hudson – allegiant to the cause, devoted themselves to this challenge and other ballistic puzzlers unique to the new-fangled, small-bore metal jacketed bullet.

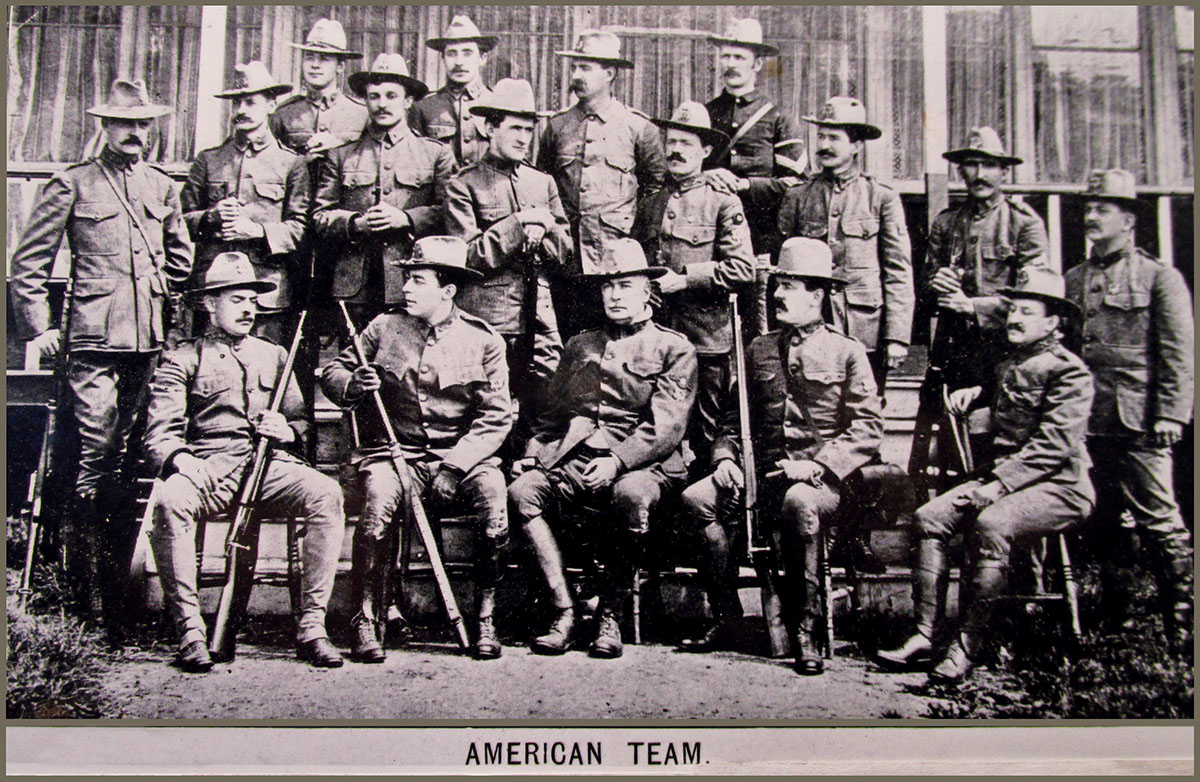

The next September, the U.S. fielded a team for the 1902 Palma Match at the Rockcliffe Range near Ottawa, Canada. Bruce was among those that went along for support. A month previously Bruce had the occasion to return to the firing line at Sea Girt to shoot his 30 shots for the Wimbledon Cup. He finished 13th out of 42 entrants.

At Rockcliffe, the Americans used the issue Krag service rifle and ammunition, with two team members taking a gamble on 1903 Springfield prototypes using “defective” cartridges. This fault was said to have been responsible for several dropped points. The British won the match fairly with 1,459 points, only 12 ahead of the forlorn Americans. The game Canadians finished third with 1,373.

In 1903, Bruce served as team captain for the victorious (temporarily) Palma team at Bisley, England. Bruce, poster child for the proverb “no good deed goes unpunished,” was made the scapegoat for the match’s disputed outcome. Bruce died at his home in Greenwich, Connecticut, in August 1911, at 62 years old.

For all the American riflemen of any age who were pulling for a successful long-range marksmanship revival, the 1902 match across the Canadian border was a victory for their cause. A Shooting and Fishing columnist considered the loss philosophically and with optimism. In the September 18, 1902 issue we find: “The result of the 1902 Palma Match is perhaps fortunate. Had the British riflemen lost the match there probably would have been no more international contests for many years… The benefit derived from the international contest this year is undoubted. Riflemen in England, Canada, and the U.S. have become well-acquainted and established friendly relations. As a result, there will be more international contests. This will stimulate improvements in arms and ammunition, increase interest in rifle practice and develop a high order of skill, which is of inestimable value.”

Lawrence B. Thompson (1934-2021)

Upon leaving the RAF, Larry began a career in the engineering field, designing super high-powered optical instruments used to assess, observe and surveil areas from extreme distances and heights. Larry had a lifelong interest in firearms and shooting, and when firearms restrictions became too severe in England, he emigrated to the U.S., where he married his wife and raised a son.

Target shooting with old rifles piqued Larry’s interest the most, and he became enamored with single-shot Schuetzen rifles made in the late nineteenth- and twentieth-centuries. This led to his involvement with the American Single Shot Rifle Association, where he was the secretary of that group for many years. Always willing to help others, he was responsible for bringing in more than a few members into that organization and promoting shooting the old rifles any way that he could.

Larry was also interested in muzzleloaders, chiefly the old-time picket and slug rifles. Larry was expert at rehabilitating many of the fine, old, target rifles and made the loading tools, bullet swages, moulds, dies and other items needed to restore the old rifles to their rightful place on the firing line.

To that end, Larry humorously referred to himself as “The Hack from Salem,” as he performed his work in Salem, Ohio, not too far from where George Sonnendecker (whom he called “The Original Hack”) had his shop.

An NMLRA member for many years, Larry was a friend and mentor to many who sought to achieve accuracy with slug rifles, and though he worked on items for many of the modern-style rifles frequently seen on the line today, he had a special affinity for the old rifles and it is because of this that I came to know him.

Larry’s skill as an engineer enabled him to design many things, including the large, superduty CH loading press and wonderful rifle scopes made in the manner of those from the old Malcolm shop.

A person with strong opinions, Larry was not reluctant to challenge the status quo when he felt it necessary. When he was seriously injured by a barrel explosion in the 1980s, Larry worked hard toward improving the quality of barrel steel and methods in use at that time to make muzzleloading barrels, so others would not be injured or maimed.

Larry worked hard at promoting slug rifle matches whenever he could, and for many years, was the driving force behind the Walter Grote Matches held at Canal Fulton, Ohio, which continue to this day, along with the Originals Match, held for original slug and picket rifles made before 1900.

When I joined the Canal Fulton Club in the 1980s, I knew of Larry but never really had the chance to speak with him until I went to the International Long Range Match in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, in 1994, where he was involved with the U.S. team. I mentioned to him I had an old picket rifle I wanted to shoot, and that was it. Over the years, Larry was a great friend and mentor to me, and the things I learned from him I could have learned from no one else.

I attended Larry’s funeral, along with other slug shooters he mentored over the years. In the room where we sat, a person made a statement about what type of bullet would be most accurate at the longer ranges and a lively discourse developed over the issue. I thought it rather poignant that at Larry’s funeral, there were slug-rifle shooters disagreeing over bullet design. I was saddened that Larry could no longer chime in, but I think he would have liked that just the same.

A great man, he will be missed by many.