10-Gauge Black Powder Shotshell Reloading

feature By: Lon Morris | March, 23

To get started, here is a little history of my loading black-powder shotgun shells. I began loading black-powder shotshell cartridges when I was 12. I had started shooting trap with my dad’s old Model 12 Winchester at the local trap range in Riverton, Wyoming. Dad quickly realized that at the rate I was shooting up boxes of shotgun shells, this sport was not going to be economical feasible for the family very far into the future. So, ever resourceful, he found a neighbor who had given up shooting shotguns and had a complete shotshell reloading outfit he would sell for $10 (circa 1962). This complete shotshell reloading outfit consisted of a 12-gauge Lee Loader, a mostly full 8-pound keg of Red Dot powder, a huge bag of Number 8 shot, a large bag of Alcan Wads, several hundred primers, another large bag of empty paper shotgun hulls. Most importantly, but not recognized at the time, was a can of Dupont 2Fg black powder. At any rate, Dad and I began a hobby that we enjoyed together for more than 50 years. Another benefit was that I was excused from going to church on Sunday mornings, as I was heavily involved in becoming an up-and-coming trap shooter.

I reported the incident to Dad, and he said it was no problem as we would load the Lefever with black powder. So, we did. The next Sunday, Dad dropped me off to shoot trap, and I had my prized LeFever. Nobody paid much attention to the “kid” as I stepped to the 16-yard line, shouldered the old LeFever and called “pull.” There was a roar, a billow of white smoke, and the next thing I knew, the whole club was standing around me wondering what happened, was I okay, and what happened to the gun? When I confessed that I had shot the old LeFever with black powder, there was a general sigh of relief, and they told me never to bring that thing back to the trap range. I did notice that the shoot became a little more lighthearted concerning the kid bringing a black-powder shotgun to shoot trap. Later during the shoot, while I sat on the bench watching, one guy asked if I would like to shoot a round with his Winchester Model 12 Trap Grade shotgun, as all I had to shoot was my outlawed LeFever. Two important things happened that day: I shot my first handloaded black-powder cartridge and learned there are politics in competitive shooting!

One thing that puzzled me for 55 years after the above mentioned event, was how Dad knew how to load a black powder shot shells? Several years ago, I got an idea to see how a black-powder loaded shotshell would perform on pass shooting ducks in a 10-gauge, 3½-inch Magnum loaded with No. 2 steel shot, buffered, with a plastic shot wad, all in a plastic shotshell hull. I bought a Lee 10-gauge 3½-inch loader on eBay, and right in the directions was the procedure for substituting black powder for smokeless powder. It was that simple!

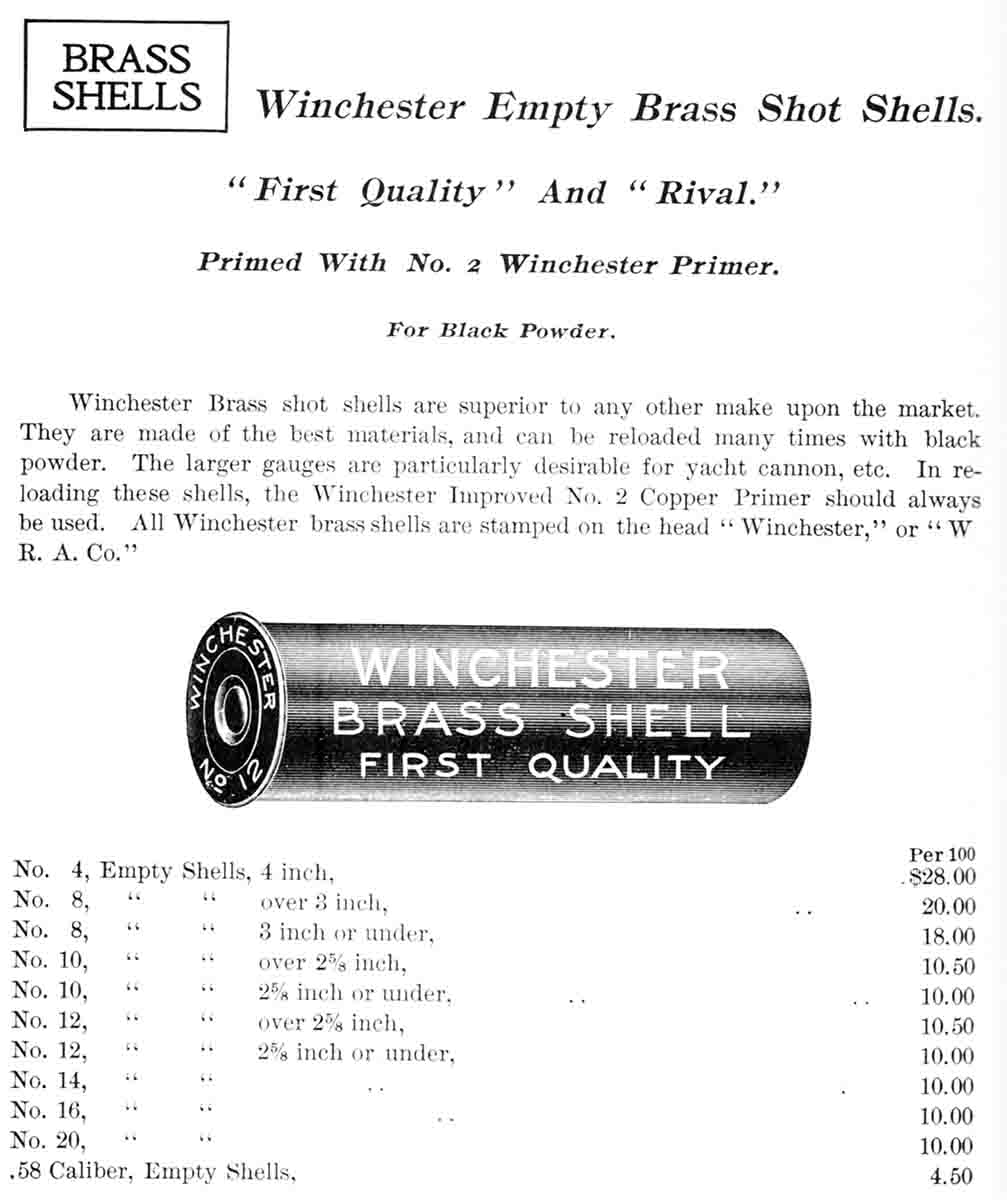

Extruded cases are not available for the usual 209 series shotgun primers currently being produced and reseating standard rifle or pistol primers can be problematic for the reloader using basic tools to reload their brass shotgun shells. RMC manufactures 10-gauge hulls on a regular basis and I believe they are the only player in town producing brass 10-gauge cases. RMC cases are precisely uniform (they use CNC machinery) while other brands of drawn brass hulls require oversized wads to seal the powder gases in the case and bore. I understand that current production drawn cases are significantly too short for most chambers as well. The case should fit to the edge of the forcing cone to give quality patterns.

While there, I purchased their “Shot Shell Loading Kit,” for 10-gauge. This kit includes a stud loading collar, brass depriming cup, steel priming base, depriming shaft, a case mandrel and instructions. The quality of this kit is fantastic, and the instructions are very easy to read and understand, with no foreign language accidentally left in the instructions to try and sort out!

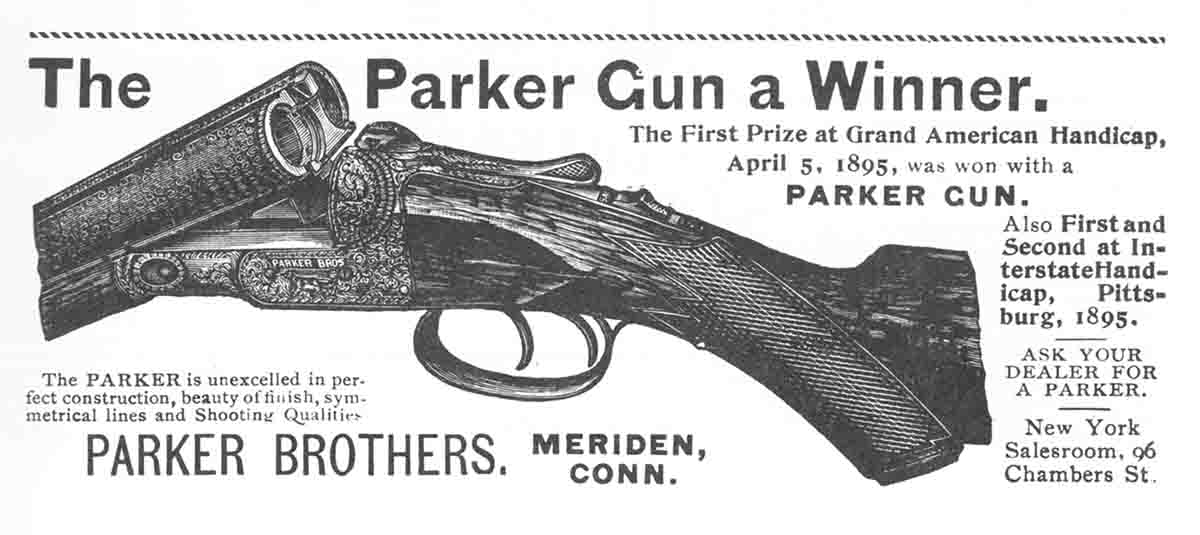

I freely admit that I have a soft spot and a genuine weakness for shotguns, especially side-by-side doubles. I have loaded countless trap loads, including specialty loads with smokeless powder, and over the years, some novelty loads with black powder. When I started this project, I decided to validate my thoughts and conclusions as to black-powder charges through various sources that would be deemed credible. My first source was the two-volume set of extreme quality books, The Parker Story by Gunther, Mullins, Parker, Price and Cote. It is easy to get lost in these books, because of the historical documentation, especially on grades and gauges of the Parker gun. However, I could not find any loading information for black-powder cartridges. Next, I looked to Cartridges of the World by Barnes, but again, no specific load data for black-powder shotgun shells. However, I did find a definition for “dram equivalent,” and this is important information for anyone loading black-powder shotgun shells. “A Dram is a unit of measure. There are 16 drams (av.) in one ounce, or 256 drams in a pound. This equates to approximately 27 grains per dram. In the early days of black powder shot shells, the powder charge was measured in drams. Dram for today’s smokeless powder is more powerful. When loading a shell with smokeless powder a smaller weight of powder is necessary to give same muzzle velocity as would be obtained from black powder.”

Now, I suspect this is the point in the article where some of the readership will start “screaming like a gut-shot panther!” Their outrage will be that this is not a traditional loading technique. They are absolutely correct and here is why. I am the owner (caretaker) of a quality 10-gauge Parker hammer gun built in 1888. It has flawless barrels and I demand the upmost protection for those barrels. Furthermore, my hunting partner, Turbo (my three-year-old lab) demands perfection, as he is usually 30 yards directly in front of the old Parker, and bears the brunt in his ultra-sensitive nose of 3½ drams of 2Fg black powder pushing a shot payload in excess of 700 grains without ear protection. He gets rather surly when he endures the above torture and there is nothing to retrieve! This is where the “pattern board of perfection” comes into play and the pattern board does not lie.

We might as well get the perceived “negative” out of the way; that being melted plastic in the bore of the gun. I have been loading self-cut mylar wads over black powder since 1990, in my BPCR rifles and continue this practice to this day. They are popular enough that today they are available through commercial production. All one has to do is to walk out in front of the shooting line at any major BPCR match, and you will see many plastic wads that you could pick up and shoot again, showing no distortion or melted edges. I have loaded and shot black powder with plastic wads and other components in several 10-gauge 3½-inch Magnum shotguns, using maximum steel and heavy lead shot, at velocities that would give Elmer Keith pause. Going a step further, I pick up and saved the shot cups that have been used on the patterning board. Again, no melted edges; however, they are radically deformed (just as they are designed) to allow the best possible shot string, and consequently outstanding patterns. There is no residual plastic fouling in the barrel.

Now, that being said, I did buy a Remington 870 TC Trap Grade shotgun that had outstanding wood. Trap guns are like .22s, in that usually they don’t get cleaned. This gun had to have shot several thousand rounds without being cleaned. It probably quit shooting decent patterns and down the road she went. It had bad plastic fouling in the forcing cone area of the barrel. I clean all of my guns with Hoppe’s No. 7 powder solvent and commit the ultimate “horror of horrors” by using Sweets 7.62 to clean during the break-in process of the barrels on all my rifles, and during general maintenance. The trick is that I use MEK (methyl ethyl ketone) to clean between powder solvent iterations and also to clean all traces of solvent out of the barrel before I run a patch of G-96 down the barrel for storage preservation. The label on the MEK can reads, and I quote, “Powerful Thinning and Cleanup Solvent, Use with Rosins, Epoxies, Adhesives, Fiberglass, and Lacquers. Fast Drying no Residual.” Be careful not to get MEK on the finish of your stock! Anyhow, MEK cleaned up the 870 shotgun, pronto, and I have used it since 1990, when I started shooting mylar wads as part of my cleaning regime. So, if you are concerned about plastic fouling, just run a patch of MEK down the barrel.

Supplies include the following for this project, and I am not sure if some of these items are currently available, but similar items can be substituted:

• Rocky Mountain Cartridge, LLC brass shotshell cases

• Remington STS-209 Primers

• Remington No. 5 shot

• Ballistic Products Inc. 10-X Gas Seal wad

• Ballistic Products Inc. 10-gauge Deci-Max shot wad

• Mica Wad Lubricant

• Precision shot buffering

• Ballistic Products Inc. 10-gauge overshot wad

• Tube of Duco cement

Deprime the case by placing the case on the depriming cup. Insert the depriming shaft into the case and use a hard rubber or leather mallet to deprime the case.

Reprime the case by setting a 209 primer on the smooth steel base, place the shaft into the case with the depriming stud removed. Then, gently tap the case onto the primer until it is flush.

Place 20 or so plastic gas seal wads and an additional 20 plastic shot wads into a large plastic bag and pour a small amount of wad lube into the bag, seal the bag, and thoroughly shake the wads and lube. The wads are now lubed and store the wads in the bag.

Place the loading collar onto the case mouth and pour the powder into the case. Place the lubricated gas seal wad into the collar and seat the wad on the powder with shaft. Place the lubricated shot wad into the collar and press the shot wad home again with the depriming shaft. Make sure you unscrew the decapping pin from the shaft!

Pour the shot through the collar into the shot wad.

Measure 20 grains of shot buffering and slowly pour the buffering onto the shot, while gently tapping the entire case on the steel plate. This will settle the shot into the shot wad and the buffering into the shot. Continue tapping until the shot buffering is mixed with the shot.

If your powder charge, wad column, and shot charge are in the correct proportions for the case, you should have a slight space where the case extends above the shot column. Take a 10-gauge over-shot card wad, place it on the shot column, and use the shaft to gently press the card wad down on the shot, with no airspace.

Also, do not add various wads over the top of the shot charge, as these wads will negatively impact the pattern. Elmer Keith believed one of the best improvements to shotshells was getting rid of the overshot wad and replacing it with the folded crimp. Lastly, take a ¾-inch label dot, mark your size shot on the label, and place the label on the solidified SPG. This will be a nice finishing touch to your shotshell.

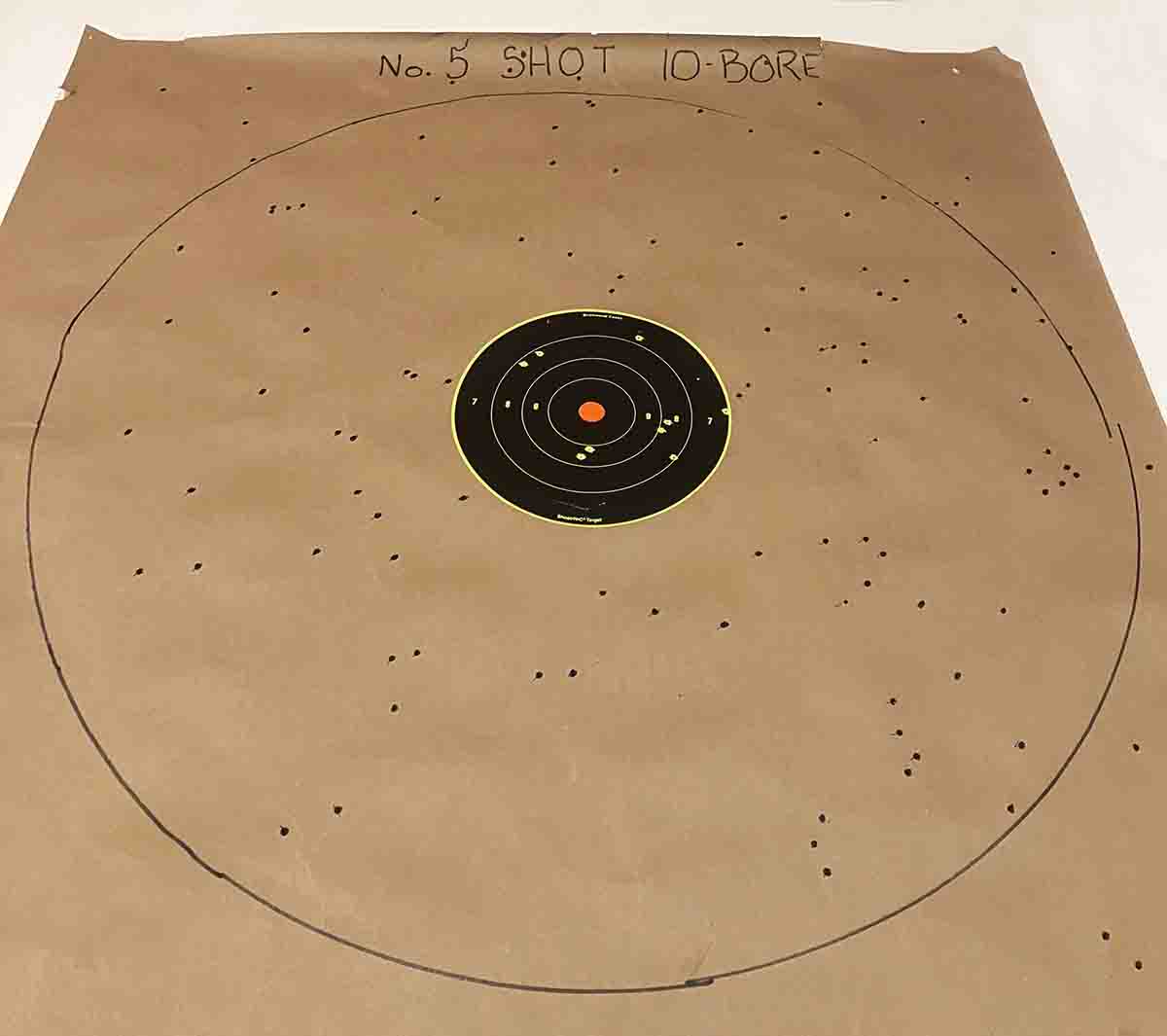

Speaking of the way it shoots, here are the results for my 1888 Parker 10-bore.

I set up the pattern target at 40 yards. I placed an 8-inch Birchwood Casey target onto a 35-inch square piece of paper. I drew a 30-inch circle around the center of the 8-inch target. The stick target served as an aiming point in the center of the 30-inch ring. Now this is significant, as some shooters move the 30-inch ring to give the best percentage of shot into the 30-inch circle. By count, the 1888 Parker 10-Bore shot this load into a 62 percent pattern. I was especially pleased with the even shot pattern, and at 40 yards this would be a lethal pattern, especially for rising upland game birds.

If this article has encouraged you to grab that old Damascus double gun out of the back of the closet and shoot it with brass cartridge cases, I hope you do!