One Shot with Old Powder

feature By: Mike Nesbitt | March, 23

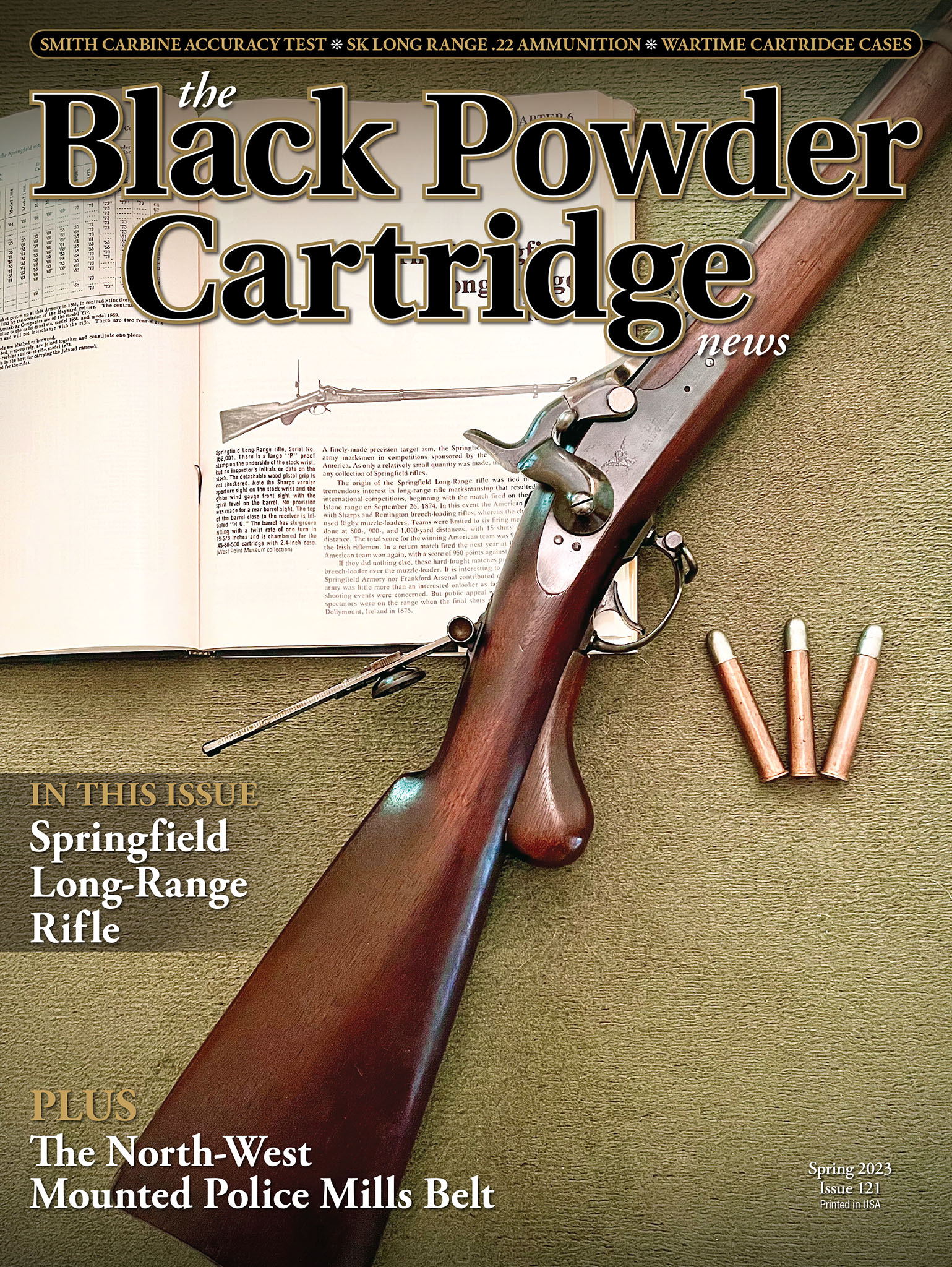

As was done with the “Dissecting a .44-77,” this description is being written as I go along. I will admit, right from the start, that I’m not absolutely sure about the age of this powder. Someone might have changed the powder already, just like I’m about to do, but I don’t think so. The powder has a look and a weight or density that I’m not familiar with. So, I must assume this is the original powder loaded into the old cartridge.

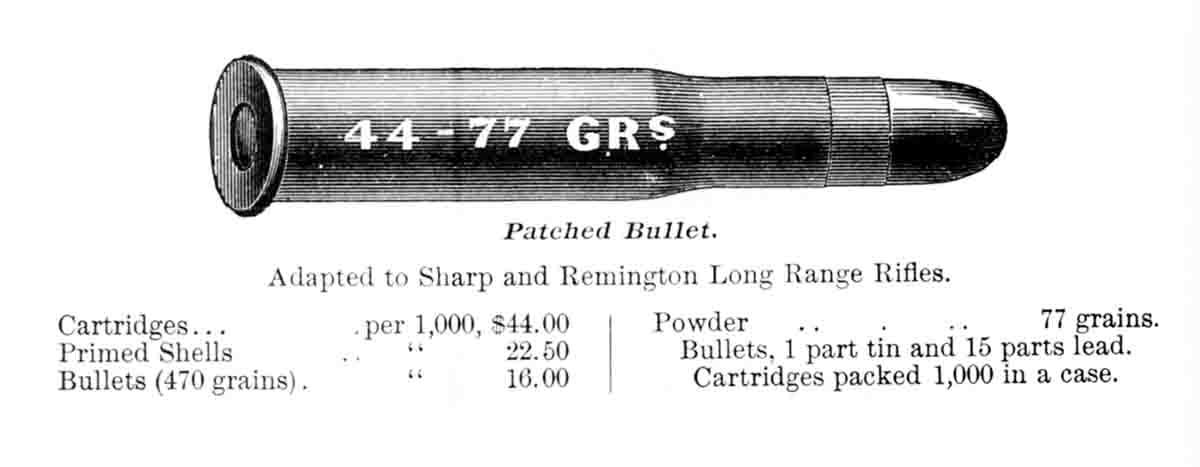

To make up the load, the old powder was drop-tubed into a new, unfired Jamison .44-77 case. Primers used were Federal Large Rifle Magnums. The level of the powder was just about halfway down the neck, so only a little compression with an .030-inch card wad was needed to make room for the 1⁄8-inch lube wad before seating the bullet. A patched 405-grain bullet from a KAL mould was then seated over the lube wad, deep enough to give the cartridge a 3-inch overall length. As soon as it was loaded, the primer of that cartridge was colored with a red marking pen so it could be quickly identified from the other loads.

Following that, the old original case was then charged with the 76 grains of Swiss 2Fg. The level of the powder was much further down the neck in the old case, suggesting greater volume inside the case. That could be true, but also, the old case has larger outside measurements than the unfired Jamison brass. Things could be much different if fireformed cases were being reloaded. With the old bullet seated back in the original case, that old cartridge was ready for the collection again.

I was so worried that something would go wrong, which could mean the velocity of this one shot couldn’t be recorded. So, no detail was overlooked. But in fact, I was focused on little details so strongly that one big detail did get by me, when I got to the range to do the shooting over the chronograph, I had forgotten to bring the rifle! Jerry Mayo, my shooting partner and I, had a good laugh over that. Then we retired to the Littlerock Saloon and the drinks were on me.

The next day, we met at the range again, at the same time when the sun was in a favorable position for our shooting and chronographing. The chronograph was set up a good distance in front of the shooting bench so that smoke from the shots would not cause “errors” in the readings we wanted to record. That “good distance” was 30 feet. With a target posted at just 50 yards, primarily for an aiming point, we were ready to start.

Then some preliminary shots were taken to check out everything, including ourselves. I shot some of my older paper-patched loads through the .44-77 and Jerry shot some of his .45-70s over the chronograph. All worked very well and our curiosity about those loads was satisfied. As an example, I shot some previously loaded rounds for the .44-77 and used the same 405-grain bullets, but with only 70 grains of Olde Eynsford 1½ powder. Those three shots averaged just 1,250 feet per second (fps), about 100 fps below what a .44-77 is supposed to do.

The two loads using the Swiss 2Fg powder had both hit the target well-centered, and I had no idea where the bullet fired with the old powder would hit. I had some fears that, for some reason, the powder wouldn’t burn properly and the shot might go too low. In fact, the opposite was true. To me that shot sounded louder, with a greater “crack!” The smoke from that powder was definitely a different color; it was an almost dull, silver/grey instead of the bright white with a bluish hue of the Swiss powder. Things were certainly different.

I will have to always wonder if that old powder had lost any of its energy over the years while it was confined inside the cartridge case. My guess is that it didn’t because the velocity we got when the round was fired was still within the common velocity spread that is often encountered when chronographing loads. Yes, that is making a comparison of one, which we should never depend on, but in this case what else can we do?

Shooting that one shot with the old powder was a complete success and what made it such a success was the fact that it didn’t hit Jerry’s chronograph! After all, we had no real idea of where that bullet would hit, elevation-wise. There was no way to test the powder beforehand and everything about that shot was based on estimates or “what it should do.” We can’t expect this one shot to give us any real conclusions other than to weigh the things we observed when the shot was taken. All of those observations to add up, in my opinion, to show how the powders used “in the old days” was certainly very good and we did enjoy taking this little peek into yesteryear.