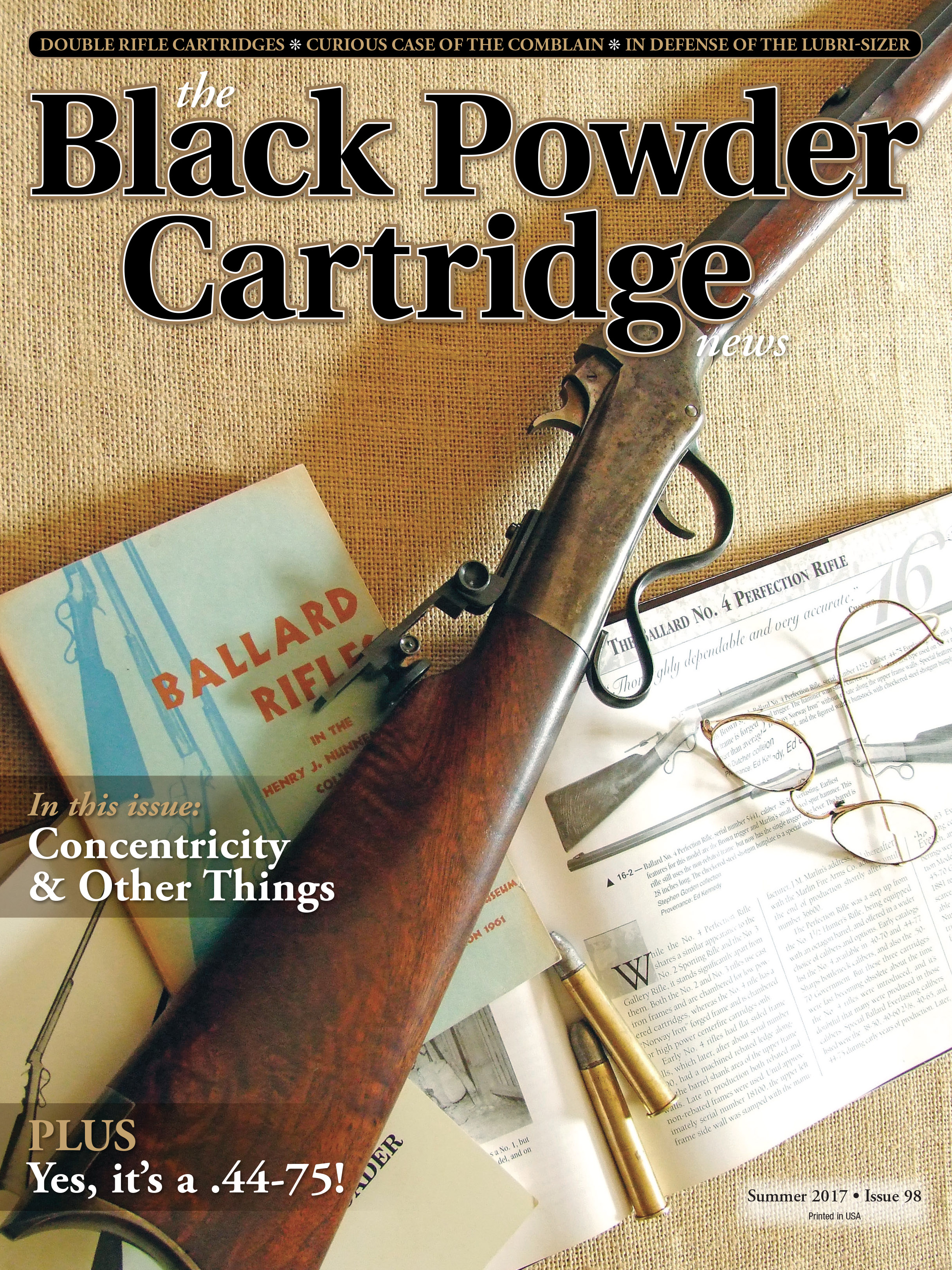

Black-Powder Cartridges

For Double Rifles

feature By: Cal Pappas | June, 17

The Victorian era saw the transition from flintlock to rimfire and centerfire black powder cartridges as well as the early years of nitro propellant. The Edwardian era followed, and while used to denote the United Kingdom firearm trade from 1901 to World War II, it was actually just the years of Edward’s rule, 1901-1910. While the Edwardian Era was totally in the nitro-express period, many hunters used and ordered new rifles made for black powder well into the first decade of the new century. A few reasons account for this: Old habits die hard, black powder had proven itself for centuries, black powder was more reliable and stable than nitro in the early days, and black powder was not affected by the heat of the tropics. If jacketed bullets, both softnose and solids, had been present with black-powder cartridges, perhaps the popularity of black powder charged cartridges would have lasted much longer into the nitro era than it did. After all, lead bullets do limit penetration.

Below are the five basic bore diameters common in the express rifles and the six most common bore rifle sizes. Cartridge books will list well over 250 different examples of express and bore rifle cartridges – those being separated by case length, case type, case shape, powder charge, bullet weight, bullet style, bullet diameter, headstamp and maker. The stats listed below are only for the cartridges and calibers charged with black powder. Their nitro cousins are not included therein.

.360

Variations: 20+

Case length from: 1.05 to 27⁄16 inches

Powder charge: 14 to 55 grains

Bullet weights from: 72 to 215 grains

Most common: 21⁄4 inches, 55 grains powder, 215 grains lead

The most popular was the .360 21⁄4 inch, about on par with famous American cartridge, the .38-55. Fifty-five grains is the same charge as two drams (27.5 grains per dram) and the .360 was charged with two drams making it an ideal small-game cartridge for single shots and a few double rifles. With recoil being about nil, it was popular with youngsters and women. In 2008 I handled a W.W. Greener boxlock top lever in .360 21⁄4 inch on a ranch in Zimbabwe. The rifle had zero finish remaining, off face, rough bores, and the checkering was worn flat. It had been used on a Zimbabwean ranch since the earliest colonial days. If rifles could talk!

.400

Variations: 33+

Case length from: 2 to 31⁄4 inches

Powder charge: 75 to 110 grains

Bullet weights from: 210 to 374 grains

Most popular: 23⁄8 inches, 83 grains powder, 230 grains lead

Of all the variations in the .40 caliber, two stand out as the most common, those with case lengths of 23⁄8 inches (a small game and deer cartridge) and the 31⁄4-inch case (for medium game).

.450

Variations: 68+

Case length from: .85 to 31⁄2 inches

Powder charge: 25 to 142 grains

Bullet weights from: 214 to 530 grains

Most popular: 31⁄4 inches, 110 grains powder, 270 grains lead

The most popular bore size in the U.K. and far more popular than the .500 in Africa, there is no doubt the 31⁄4-inch case ruled the roost of the .45 calibers.

.500

Variations: 32+

Case length from: 11⁄2 to 31⁄4 inches

Powder charge: 45 to 164 grains

Bullet weights from: 340 to 570 grains

Most popular: 3 inches, 136 grains powder, 340 grains lead

More popular in India than any other cartridge (except perhaps the .303), India had far more sportsmen there than ever trod the veldt in Africa. This was due to the fact that Africa was populated with white farmers and a few hunters, whilst India had a large military presence containing officers (with highly embellished rifles) and enlisted men (with plain finished rifles) longing for hunting activities when off duty. The .500 BPE double rifles seem to outnumber all other calibers. The .500 was a deer cartridge in its 3-inch case with 340-grain bullets and a fine buffalo and tiger cartridge with the heavier 440-grain bullets.

.577

Variations: 25+

Case length from: 11⁄4 to 31⁄4 inches

Powder charge: 50 to 192 grains

Bullet weights from: 480 to 713 grains

Most popular: 23⁄4 inches, 165 grains powder, 570 grains lead

The .577 was the heavy weight of the black powder express cartridges. The 3-inch version was the most popular for sporting purposes (not including the military Snider round) and was a true big game express rifle. The 620- and 650-grain bullets were used against buffalo, gaur, lion, tiger and bear. Elephant, rhino and hippo were stretching its capabilities a bit with lead bullets, but the largest of game certainly did fall to the mighty .577. However, the larger bores were not infallible. One hunter in India fired 11 shots into a gaur, the largest of wild oxen at 3,000+ pounds. At the end of the battle, the quarry killed him.

Now, to the bore rifles. As time progressed in the latter decades of the 1800s, the bore rifles became more powerful, and the rifles added weight. For example, an 8-bore in the 1870s had the power of a 10-bore in the 1890s. A 4-bore in the 1870s had the power of an 8-bore in the 1890s.

20-bore (.620 Inch)

Variations: 18+

Case lengths from: 2 to 23⁄4 inches

Powder charge: 83 to 110 grains

Bullet weights from: 350 to 400 grains

Most popular: 21⁄2 inches, 83 grains powder, 350 grains lead

16-bore (.665 Inch)

Variations: 12+

Case lengths from: 2 to 23⁄4 inches

Powder charge: 110 to 136 grains

Bullet weights from: 437 to 500 grains

Most popular: 21⁄2 inches, 110 grains powder, 437 grains lead

As with the 20s, the 16-bore with a 1-ounce bullet (ball) and 3 to 4 drams of powder was still a light, small-game rifle.

12-bore (.729 Inch)

Variations: 46+

Case lengths from: 21⁄2 to 3 inches

Powder charge: 136 to 192 grains

Bullet weights from: 593 to 700 grains

Most popular: 21⁄2 inches, 136 grains powder, 593 grains lead

10-bore (.775 Inch)

Variations: 15+

Case lengths from: 25⁄8 to 3 inches

Powder charge: 165 to 220 grains

Bullet weights from: 700 to 1,000 grains

Most popular: 27⁄8 inches, 165 grains, 700 grains

8-bore (.835 to .875 Inch)

Variations: 38+

Case lengths from: 27⁄8 to 33⁄4 inches

Powder charge: 275 to 390 grains

Bullet weights from: 875 to 1,620 grains

Most popular: 31⁄4 inches, 275 grains powder, 875 grains lead

While the 10-bores begin the big-game, bore rifles, it is the 8-bore that really shines as the most popular big-game, double rifle in the bore designation. While early 8s were relatively light, it is the 8-bore in its 16 to 17 pound weight that speaks elephant and rhino. With common bore diameters between .835 and .875 inch, the author has personally seen 8s from .818 up to .888 inch. A true 8-bore spherical ball (.845 inch bore diameter) weighs 1⁄8 of a pound or 875 grains; the .875-inch ball of a large 8-bore weighs 1,000 grains (a 7-bore in actual size). Conical bullets begin in the 1,100-grain range up to 1,620 grains and more.

4-bore (.970 to 1.052 Inches)

Variations: 17+

Case lengths from: 31⁄2 to 41⁄4 inches

Powder charge: 330 to 440 grains

Bullet weights from: 1,400 to 2,100 grains

Most popular: 4 inches, 390 grains, 1,400 grains

Charged with 14 drams and sometimes a full ounce or 16 drams (440 grains), the recoil is devastating – even in a 24-pound rifle! That said, gun writers and gun owners have a strong tendency to exaggerate, and reports of a 20-dram 4-bore charge of 550 grains and a 2,400-grain conical bullets are doubtful. No one will ever know the total of 4- and 8-bore variations, as many customers would order a diameter and bullet weight combination and have a single rifle made to their requests. This makes collecting and researching so much fun!

To compare vintage rifles, it is my opinion the finest workmanship came from rifles in the Victorian Era as compared to those of the later years. This is not to state the latter quality was inferior, but over time engraving styles changed from the fine and tight scrolls to a more elaborate work. Even later, after World War II, the style and quality diminished, as James Watts (.450 Watts fame) told me, many (if not most) of the gunsmiths died during the war. Others were elderly and retired, quality materials were in shortage, factories and the tools were destroyed and tastes among the buying public changed. In other words, a 1950’s Holland Royal did not have the quality of a 1920’s Holland, and the 1920 Holland, while of equal quality to older rifles, did not

I would like to thank cartridge collector extraordinaire, Dennis Bromley of Anchorage, Alaska, for opening only a fraction of his collection to me. Dennis probably has an example of 99.9 percent of the sporting and military, black-powder and smokeless, vintage and modern cartridges known to man! He actively buys, sells and trades his passion and has an amazing collection of American black-powder cartridges from Sharps, Winchester, Remington, etc. If you have the same passion as Dennis, you can reach him at: dennisbromley@yahoo.com.

Please note: For the table I chose a common bullet weight and an average charge of powder. Velocity figures are taken from a combination of pub-lished ballistics, my own chronograph numbers and maker’s numbers (taken from long test barrels). Also in the table is a column headed as Taylor’s knockout value. John Taylor was, perhaps, the best-known authority on double rifles and their use in Africa. Knowing the calculation for muzzle energy that is the result of squaring the muzzle velocity, Taylor developed his knockout value. The KO value added into the calculation of the bullet’s diameter and relied less on the velocity. Bullet diameter times bullet weight times velocity divided by 7,000 is his KO value. It basically gives larger and slower velocity cartridges a means to compare one to another. Example of two KO values of a modern and black-powder cartridge to compare with the list: .30-06 180-grain bullet is 21.3 and a .45-90 Winchester, 300-grain bullet is 27.4.

.jpg)