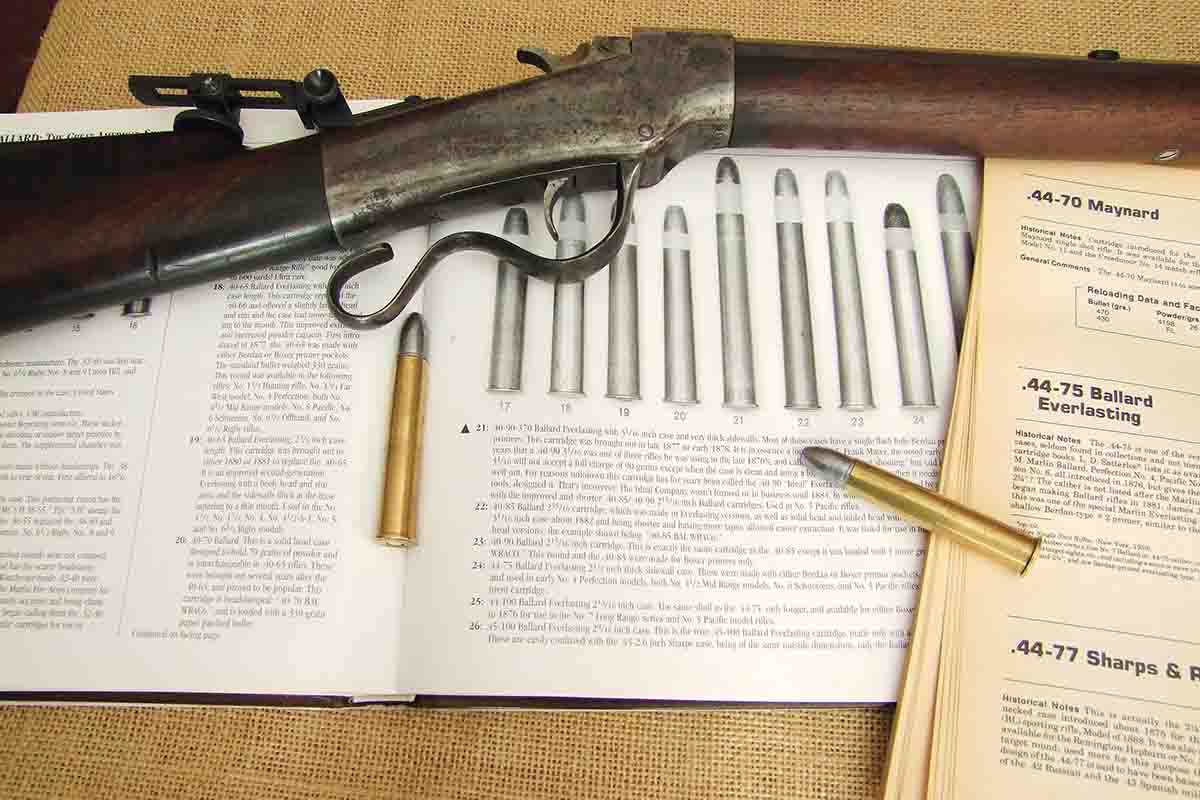

Like this article’s title, I did a double take when I read the ad for a No. 4 Ballard on the Guns International website: A .44-75 . . . What? It must be a misprint. You mean a .44-77? No. You mean a .45-75? No. You mean a .45-70? No. This is what went through my mind as I read the ad content. This had to be somehow confirmed! I checked John Dutcher’s book, Ballard, The Great American Single Shot Rifle, in the section on Ballard cartridges. Sure enough, there it was, a .44-75 Ballard Everlasting and a rather imposing cartridge it appeared to be. I also went to George Layman’s book, A Guide to the Ballard Breechloader, to see if he mentioned it also. He did. The next step had me contacting the dealer who placed the ad. I asked him if the barrel or any other part of the rifle was marked with the cartridge designation. The dealer said, “Let me check . . . can’t find any cartridge marks at all.” This is not uncommon on early Ballard rifles, and this was an early specimen with a 1,500-series serial number, a Brown Manufacturing-style hammer profile and a “non-standard” No. 4 lever, probably the first or second year of manufacture (1875-76).

Early production Ballard No. 4 Perfection in .44-75 Ballard Everlasting.

He then told me that it was a consignment rifle, and the owner was the one who declared the chambering. I hoped he was right because according to Layman’s book, the cartridge was extremely rare. Finding a mere cartridge case would be an exercise in futility and again, according to Layman’s book, “Finding a rifle chambered for this rarity would be equally as difficult.” This is the kind of find that really excites a collector like me – rarity and challenge! After a brief exchange regarding its condition, I bought it. The ad photos showed a used rifle in rather good condition with the description text declaring a “very good bore” and, for a hunting-grade Ballard, exceptional buttstock wood. The price was also amazingly reasonable. Hopefully another Ballard gem was on its way to my collection!

The seller was from Idaho, a neighboring state of Montana, so shipping was fairly quick. The geographical location of this rifle

Early four-digit serial number on Ballard .44-75.

had visions of buffalo hunters with heavy-barreled rifles over cross-sticks flashing through my mind, and among them this Ballard .44-75. When the package arrived I was like a kid at Christmas. I got down to the actual contents and was very pleased. Here was a classic No. 4 Ballard in really nice condition for its age. As mentioned above, it was such an early piece that it used some leftover Brown Manufacturing Company parts, most notably the hammer, under-lever and trigger. The default “Standard” No. 4 levers are the ring style. It also had the early rifle-style buttplate, which is slightly smaller in height than the later Ballard rifle-style buttplates. The sides of the breechblock were finished to a smooth, machined mark-free surface – another characteristic of early Marlin Ballards. The action was free of any rust or pits and exhibited a bright and shiny surface with areas of case color coming through.

The barrel was an almost uniform plum brown. And now the crowning feature of this antique beauty – the bore; it was nearly

Ballard action open, showing the typical fine Marlin Ballard metal finish and muted case colors.

perfect! This feature excited me more than anything, as it is such a rare occurrence. I have several late nineteenth-century single shots and just a handful of them have bores equal to this one. The buttstock wood, upon close examination, was also much better than average plain wood buttstocks on my other Ballards, including my other No. 4 in .40-63.

The rifle was ordered with a 32-inch barrel, putting its weight at 10 pounds, 10 ounces. This weight is needed to help dampen the felt recoil, especially with its rifle-style crescent buttplate. The rifle also came with what appeared to be a well-made, non-original tang sight with a screw actuated windage adjustment, with the elevation achieved by loosening the eyepiece and moving the assembly up or down. There was no maker indicated on the sight, unless it was marked on the bottom of the base.

The front sight is a typical Williams-style bead, which is non-original. The only negative in the whole rifle was the drooping lever. This is another problem endemic to old Marlin Ballards. In fact, it is the only thing about used Ballards that I do not like, but tolerate.

Early Brown No.4 lever on left, later production Marlin Ballard No. 4 ring lever on right. Note different hammer configurations as well.

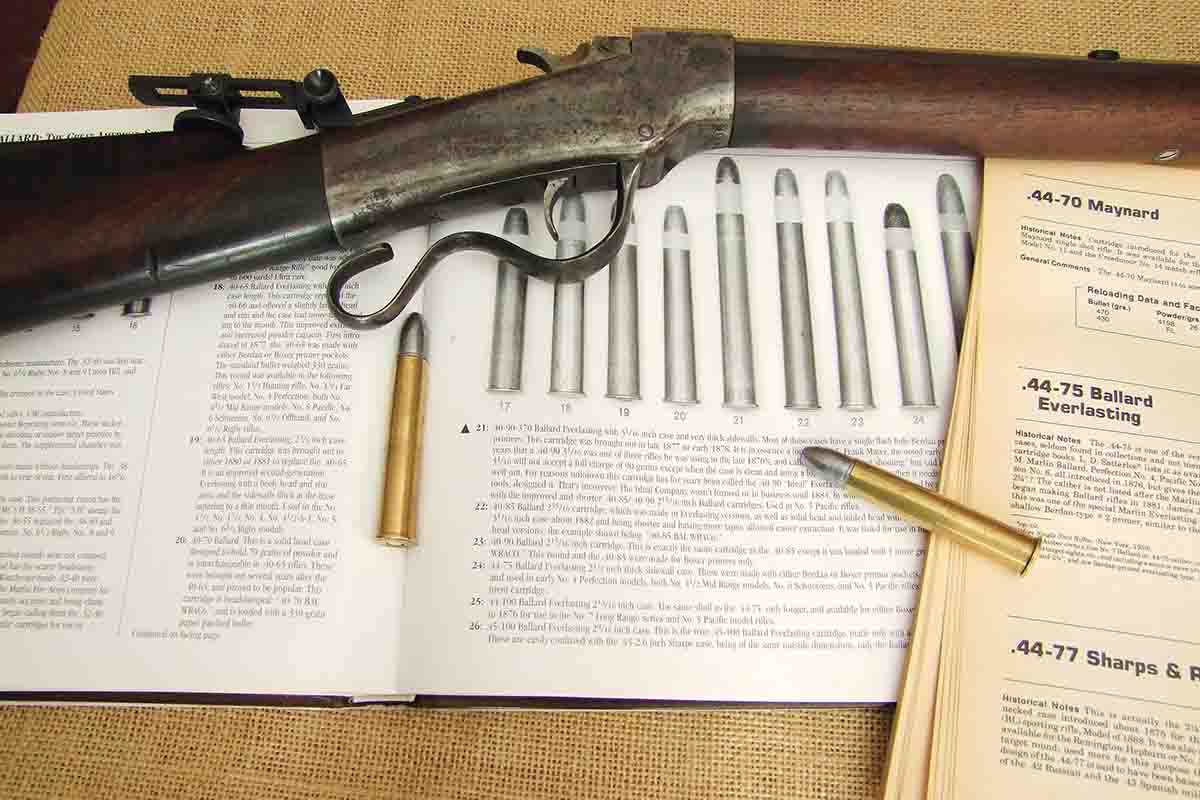

The .44-75 cartridge is the real enigma inherent in this rifle. As mentioned above, it is rare to even find a cartridge case with the .44-75 designation headstamp. Getting brass and loads for this rarity was going to be a real challenge. According to both Dutcher and Layman, the cartridge was never produced commercially, leaving the only source for the rifle owner to construct his own ammunition. This fact alone could account for its rarity. To research the cartridge, my first pick was Ken Howell’s book on cartridge conversions. Much to my surprise, since this is a pretty comprehensive tome, it was not there, essentially confirming its rarity. I then checked John J. Donnelly’s book, The Handloaders Manual of Cartridge Conversions, where I did find it. It was also in Barnes’ ubiquitous Cartridges of the World. Only Donnelly’s book had the cartridge dimensions, which I sorely needed to confirm the actual chambering.

As I always do on these old rifles, I did a chamber cast using Brownells’ irreplaceable CERROSAFE. The measurements of the cast confirmed that it was indeed a .44-75 as represented by the seller. The chamber cast revealed the measurements to be slightly larger than the actual cartridge dimensions in Donnelly’s book – not an unusual occurrence. Specifically, the cartridge head was .004 inch larger, and the case mouth area .001 inch larger. The bore, as near as I could measure it after slugging, came out to .445 inch at the breech end and .443 inch at the muzzle. Groove diameter, though hard to measure, came out around .450 inch.

Now I needed to determine how I was going to get some brass for this treasure. The casting base diameter was slightly smaller

Early .44-75 No. 4 and later production .40-63 Ballards.

than the normal .45 basic brass standard dimension; .45-90 Sharps Straight was the closest in overall dimensions though .10 inch shorter. I full-length sized one of these and tried to chamber it in the rifle but to no avail. It stuck out about the thickness of the rim. I had on hand some extra .45 Norma Basic brass cases from some prior project, so I decided to try them. I took one and shortened it to 2.5 inches, the standard length for this cartridge, then full-length sized it using a .45-70 sizer die. It still would not chamber. No surprise here. I coated the case all the way around with black liquid marker to find where it was hitting the chamber walls. As expected, it needed reduction in base diameter. Using my lathe and two centers, one dead in the chuck and one live on the tail stock, I reduced the base in front of the rim a few thousandths below the casting dimension. It easily chambered. I went through the same process with the remainder of the Norma Basic brass I had on hand. I now had 16 pieces of nearly .44-75 brass that fit in the chamber.

My next step was to fireform all the cases. This would give me what I needed to reload for this rarity. To formalize the case preparation process, see below – all material and equipment used were on hand in my loading shop:

1. Shorten all basic cases to 2.5 inches in the lathe.

2. Full-length size all cases using a .45-70 sizer die.

3. Reduce base diameter using lathe and file – check to see if they will chamber in the rifle before continuing.

4. Cap with Large Rifle primers.

5. Pour in powder charge – in this case, 22 grains of IMR-4198 was used.

6. Seat a .45-caliber King .060-inch vegetable wad over powder.

7. Pour in enough shot buffer to come within a half-inch from case mouth.

8. Set another King veggie wad over shot buffer.

9. Hand seat a cast .44 Special 260-grain semi-wadcutter bullet of .429-inch diameter.

10. Run into a .40-caliber taper crimp die.

11. Fireform cases.

Fancy buttstock on early Ballard .44-75.

This process resulted in 16 perfect pieces of brass to use in future loads to test the rifle’s accuracy. This project was really coming together! Instinctively I knew I had no mould in this diameter. Now I needed a mould.

Photos of the cartridge in my reference books showed a rather long bullet of unspecified weight. The only mention of bullet weight for the .44-75 in any of my sources was in Barnes’ Cartridges of the World, a 400- to 405-grain bullet. This seemed a little light to me. I went to Accurate Molds’ website to check for large bullet moulds about .45 caliber. My eye was caught by a .44/77 reference under its “44-445B” bullet. Checking the dimensions showed a lube band diameter of .448 inch, which would work almost perfectly in my rifle as is. I ordered the mould and a Lyman lube/sizer die of .450-inch diameter.

When the mould arrived, I cast up a bunch of bullets using reclaimed wheelweight metal that had been smelted using added

Non-factory rear tang sight, possibly an altered Axtel.

tin. It was part of a half-ton lot I had purchased several years ago and that I had been using consistently in all my match loads. The bullets came out of the mould measuring .450 inch and weighing 460 grains, 15 grains heavier than Accurate’s nominal 445 grains. These were sized and lubed with SPG Lube using the new die. For an initial black-powder load, I decided to use the cartridge designation of 75 grains. I loaded all 16 cases with 75 grains of GOEX FFg, which required very little compression after being topped with a King .45-caliber poly wad. The bullet slid easily into the case and was crimped using the .45-caliber taper crimp die I use for .45-90 loads. My records show this was a viable load with reasonable accuracy. The front sight is a rather large gold bead that does not lend itself to precise shooting. In fact, it is so large that at 100 meters it subtends the red bullseye of the 200-yard ASSRA Schuetzen target, which is 12 inches in diameter.

The .45 Norma Basic brass was converted into .44-75 Ballard Everlasting.

For my next shooting session, I wanted to develop a load using a better ratio of powder for this rather large case. To determine the maximum powder charge for this cartridge with about .100 inch of compression, I used my standard method by measuring the length of the lube/driving band part of the bullet that will be inside the case. To this figure I add the thickness of the wad, in this case .060 inch. I then subtract the .100 inch for compression, which results in the height of the powder charge from the case mouth. If it comes out to a fraction of a grain, I round it up to the next whole grain. Using this procedure, I came up with a charge of 82 grains. I loaded all 16 cases using this amount of powder and Accurate’s 460-grain, 44-445B bullet.

With the 16 rounds available I shot two groups at 110 yards. The first was nine shots after a fouler, seven of which went into 25⁄8 inches – very good considering the coarse front sight. The second group of six shots verified this accuracy, with five shots going into 21⁄2 inches. This was done on a day with some gusty wind blowing across the range on a fairly mild December day.

First nine shots from the .44 Ballard, seven going into 25⁄8 inches.

This is pretty good accuracy, and I am considering using this rifle in some of my long range shooting matches, albeit with a different front sight, in 2017. There is something to be said for the inherent accuracy in these old Marlin Ballard rifles. That’s one of the reasons I can’t get enough of them.