Keeping Up with the .44-70

feature By: Mike Nesbitt | November, 19

A great rifle from C. Sharps Arms became mine in a rather quick way, even though it sat on the “ready rack” for about eight months before I had them put my name on it. The rifle is a standard Hartford Model; however, it does have the added option of a 32-inch, No.1 heavyweight barrel. It is chambered for the .44-70 cartridge, which we could call a black powder “wildcat” because cases are simply formed by taper-necking down standard .45-70 brass to accept .446 inchdiameter bullets. That appealed to me because I expected it to offer some good shooting along with lighter recoil than the .44-77 or the bigger .44-90.

With the rifle, I got some custom Redding reloading dies (marked “.44-70 C.S.S.” meaning .44-70 C. Sharps Straight) as well as new front and rear sights. Before leaving the shop, I used their loading bench and hastily prepared 25 rounds of shiny new .44-70 ammo. Those loads used some 400 and 450-grain bullets loaded over 60.0 grains of Olde Eynsford 2F. That gave me just a few rounds to try in the new rifle on the firing line at the Matthew Quigley Buffalo Rifle Match, where I was going to arrive the next day.

Toward the end of the day but still a full hour ahead of the evening’s cease-fire, Allen Cunniff and I went back to the firing line with the new .44-70 and the 25 rounds, just to give the gun a good try. My cross sticks were set at the shooting line for the “diamond” gong which is a rather small, square-shaped target turned 45-degrees which gives it the diamond shape. That target is 405 yards away from the firing line so I guessed at an elevation, set the sights and fired, only to see the bullet strike about 30 feet low. My guess was just a little off!

More elevation was cranked in and another shot was fired. That was closer and some other close misses were noted before the cease-fire was sounded. We both tried the new rifle and certainly enjoyed the shooting. One point we noticed was the rather sharp “crack” from this new rifle. That has no bearing on this tale except that it did remind me of comments by John R. Cook in his book, The Border and the Buffalo, when he said he could hear the “booms” of the .50-caliber Sharps rifles mixed with the sharper “cracks” of the .44s.

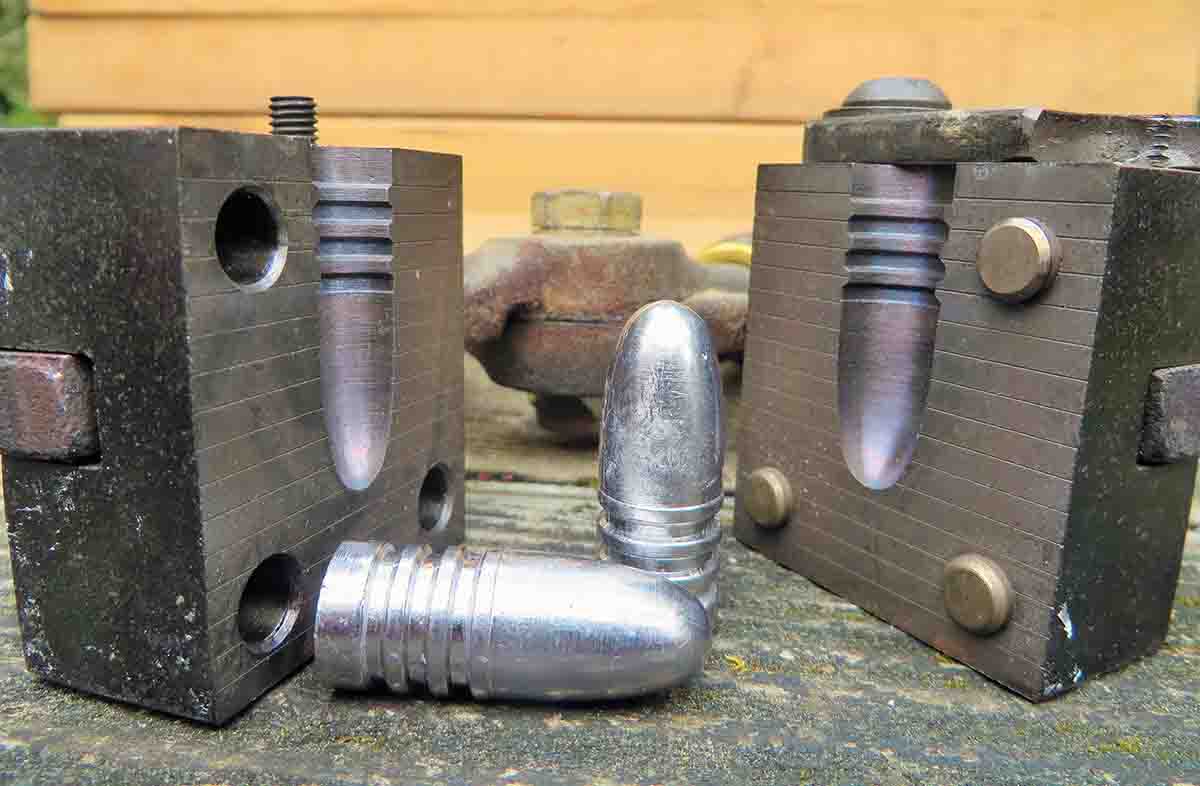

More shooting was done with the .44-70 after getting back home, with a variety of bullets, both grease-groove and paper-patched, over a fairly wide span of powder charges. Bullets from 400 grains up to 515 grains were tried, mostly favoring the lighter slugs. Powder charges varied from 57 grains on up to 69 grains. The load settled on used 60 grains of Olde Eynsford 1½ Fg powder under a fairly light original-style Postell bullet from Steve Brooks that weighs right at 415 grains when cast with a 1-25 alloy. This load pleases me in a couple of ways. In this 11½-pound rifle it has light recoil plus it performs very well on paper. It’s the load I’ll continue using until I stumble across something better, perhaps something that uses heavier bullets.

Doing well on paper targets was a prime concern to me with this rifle because it was to be used in the “Old West Centerfire” matches which our club hosts six times per year. The selection of a rifle to use for the upcoming matches actually fell to two rifles, this .44-70 and the Remington Rolling Block .50-70 that was completed shortly after the Quigley doin’s last June. The old .50-70 put up quite a fight, but the standoff ended with the .44-70 more consistently turning in higher scores.

My choice of a load for this .44-70 Sharps was made after several loads and bullets were tried, as was already mentioned. But there was more to it than that. Some of my loads simply wouldn’t shoot and I was getting to feeling a bit low about this rifle’s performance. At that point, I talked with Dennis Mitchell, a shooter I often encounter at silhouette matches. One of the first things Dennis asked me was what diameter of over-powder wad was I using? I replied that I was using the .456-inch diameter “veggie wads” that were recommended for .44-caliber rifles or .45-caliber pistols.

Dennis also shoots a .44-70 rifle, built on a custom High Wall. He quickly pointed out that for the .44-70 and other .44-caliber Sharps cartridges, the correct wads have a .446-inch diameter. With the larger wads in the load, the rifle just wouldn’t shoot well. Why? That’s really an unknown, but it must be that the oversize wads simply create an inconsistency somehow as the bullet is moving through the bore. That’s all I can say about it, but I certainly followed Dennis’s advice. When the ammo for this .44-70 (and for the .44-77) was loaded with the .446-inch wads between the powder and the base of the bullets, better results were instantly noted. From then on, this .44-70 Sharps performed very well.

That’s when my practice really began. Shooting from a bench rest was over. Using a bench is the best way to test the gun, but to test the shooter, using a bench rest can make things look too good. So, in order to see how well I would do with this new rifle in a match where the shooting is done from the sitting position with the rifle fired over cross sticks, I did my practice while shooting in that position.

Practicing over cross sticks does make a difference. I’ve found that my rifles often need a slightly different elevation setting when used over cross sticks than when they are fired from a bench. The reason for that must be in the fact that there is something different in the way the rifle is held, which allows it to recoil is a slightly different way. That means the barrel is at a slightly different attitude when the bullets exit, which results in a different point of impact at the target. Similarly, I’ve found that my shots generally hit lower when I shoot offhand than when the same rifle is shot from a bench rest. That is most evident when trying to knock over chickens in the silhouette match. Perhaps I allow the muzzle to drop slightly before firing the shot. At any rate, hits on the rail seem to be common when I try for chickens.

Then my scores in the matches fell off and my shooting with the .44-70 Sharps seemed to turn sour. Rather than dig into things to see why, I put the rifle to the side and did my shooting with other calibers. That didn’t help very much and my shooting with those other rifles, including my favorite .44-77 and .50-70, just got worse and worse. There had to be a common denominator and that turned out to be me. I was in need of some strong attitude adjustment because my sour mood was trickling into my shooting.

Where I had really gone wrong was with my bullets. I was keeping cast bullets that should have been thrown back into the pot. The problem was actually obvious, but I tried to cover that with some out-of-place reasoning. Specifically, the bullets I should have thrown back were cast with lead that was too cold or the mould was not hot enough. Those bullets were not well filled out and were sometimes a bit undersize, but they were being used anyway.

My thoughts were that because the soft-lead bullets fired in our black-powder cartridge rifles obdurate upon acceleration, or “bump up” as it is commonly called, that they would form to the internal dimensions of the barrel and give the bullets some consistency. But inconsistency was my only reward with some shots that even missed the paper. Then the doggone truth hit me; you can never achieve consistency unless you begin with consistency.

My reason for buying this rifle was to use it for mostly short-range shooting in our local matches at 100 and 200 yards. If I find a need for heavier loads, I’ll give heavy bullets another try, but for now shooting these “carbine loads” is simply working too well to try something else. That load uses the 415-grain Brooks bullet, sized .446 inch and lubed with Big Sky Lube, over 60 grains of Olde Eynsford 11⁄2Fg, slightly compressed under a Walters’ .060-inch wad, primed with a CCI #200 Large Rifle Primer, and a newsprint wad inside the case over the primer flash hole. Out of this rifle’s 32-inch barrel, that load sends the bullet out at an average velocity of 1,212 fps. This is a very comfortable rifle to shoot and meets my expectations quite nicely.

Keeping up with the .44-70 wasn’t very hard to do. It just took some falling back on a few simple basics about cast bullet reloading, finding a powder charge that the rifle likes the best, and then letting the rifle set the pace.