Pedersoli's 1886 Sporting Classic

feature By: Mike Nesbitt | November, 19

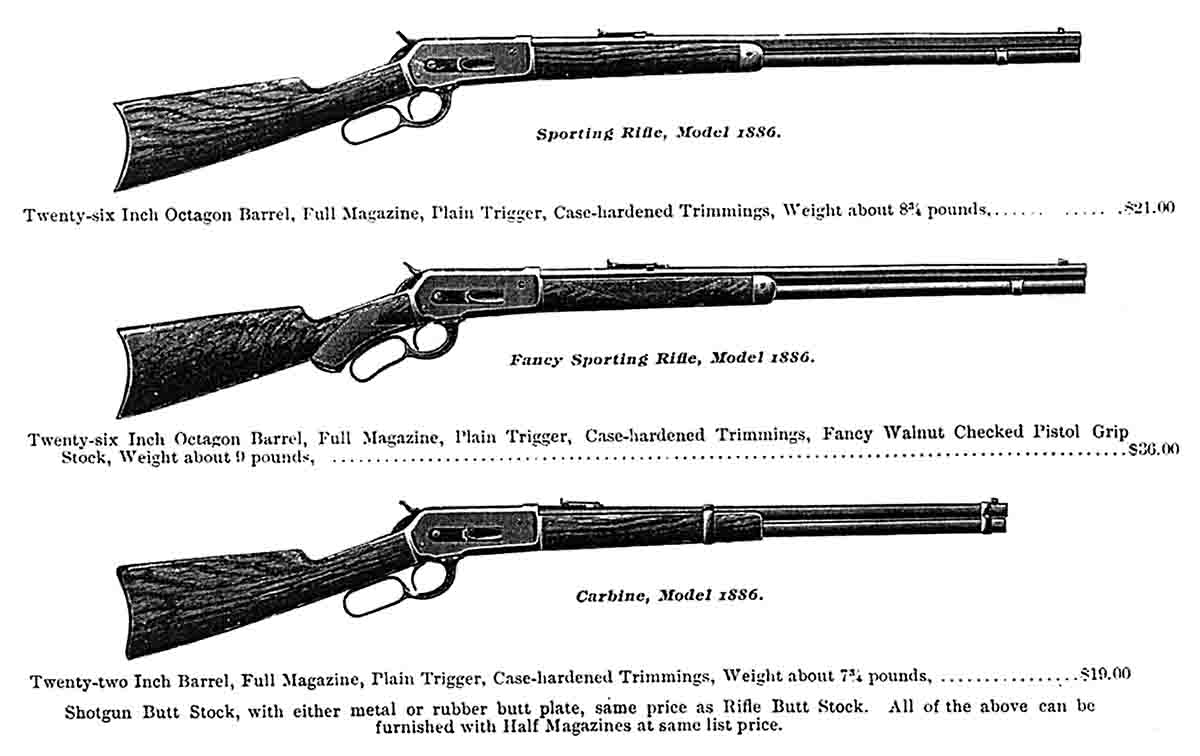

Pedersoli recently introduced another version of the old Winchester Model 1886, which they are calling the Model 1886 Sporting Classic. This new version represents the Winchester ’86 in its standard format, with no extra options, as it was when the original rifles first hit the market. The idea of no extra or added options really appeals to me because a rifle like this is probably what I would have bought if I had been a hunter back in those times. Even though Pedersoli has brought back the Model 1886 in its most standard version, this is still a copy of a rather rare rifle.

Of course, any vintage Winchester Model 1886 can be considered uncommon, if not quite rare. Over the almost 50 years of production, just under 160,000 Model 1886s were made. I’m not counting the Model 71 because, even though those rifles were fantastic, they’re not really ’86s. Out of the total 160,000 rifles, roughly only 32,000 were made with the round barrels. Even though the round barrels were standard, they were not as popular as the octagon barrels.

Those production numbers seem even less when the total output of Model 1886s is compared to the Model 1873 or the 1892. The number of ’86s is very small when compared to the total number of Model 1894s that are still being made, having been in production for 125 years.

Another standard feature seen on this Pedersoli 1886 Sporting Classic is the color-case hardened receiver. Color- case hardening was standard on the original 1886 rifle up to about 1900, or serial number 122,000. That’s about when the smokeless version appeared. Referring to Model 1886s as either “black powder” or “smokeless” is my way of putting them into categories in either the black-powder or smokeless eras. It was about 1900 when the smokeless, high-velocity loads for the .45-70 came out, as well as the .33 WCF cartridge. The .33 WCF was the only true smokeless cartridge ever chambered in the ’86. This Pedersoli version of the good ol’ Model 1886 has a nicely color-case hardened receiver as well as the forearm nose cap and buttplate.

Those standard early features seem to underline the idea for me that this Model 1886 Sporting Classic by Pedersoli is a black powder rifle. That probably isn’t exactly what Pedersoli had in mind with this gun, so please accept my comment as simply the way I look at it.

Pedersoli describes this rifle as having an English-style, straight stock made of American walnut with a round 26-inch barrel, equipped with open sights; a blade front sight and a buckhorn rear sight. The receiver is machined from forged steel and is drilled and tapped on the left side for a peep receiver sight. The tang is also drilled and tapped for the earlier style of tang sight. They say the full-length magazine will hold eight cartridges.

The wood for the stocks is certainly fancier than what Winchester used to put on a standard rifle as there’s a lot of color in the buttstock. Even though I’d still call the wood on this rifle “straight grained,” it really catches the eye. Also, I found the buttstock to be straighter than the old Winchesters by not having quite as much pitch or drop at the comb and the heel. There was no problem aiming the rifle, especially after the rear sight was raised to get the shots printing center on the target. The fit of the wood to the metal is excellent.

The front sight is a bead style, which is very easy to see and the rear sight is a semibuckhorn; easy to use as well. I have no complaints about the sights at all.

The excellent round barrel is rifled with six grooves, with a rate of twist of 1:18; that had some real influence in regard to which cast bullet to use. I’ll explain that along with my line of thinking about the cast bullets as we continue. No jacketed bullets were fired during the shooting I did with this .45-70. To me, it is really a cast bullet (and black powder) rifle. The otherwise flat muzzle is “crowned” with a slight taper to recess the ends of the rifling lands.

One feature that Pedersoli did not copy was the long, spring-steel extractor that is plainly seen on top of the bolt on the old 1886 Winchesters. To replace that, Pedersoli is using a much shorter extractor that rides the front of the bolt. No problem there, it just looks different and the shorter extractor worked just fine.

Some serious consideration was given to which cast bullet I was to use in this rifle with black-powder loads. The first bullet I thought about using was Lyman’s No. 457191, which is listed as a 292-grain bullet. My guess is that casting it with some rather soft lead alloy might bring the bullet’s weight up to 300 grains. That would be a very light recoiling load, even when the bullet is seated on top of 70 grains of black powder.

That bullet was never used, however, because it is the old design for Winchester’s .45-90 and it was generally shot out of a barrel with a 1:32 twist. I wasn’t sure the .45-90 bullet would perform well in this copy of the Model 1886. This new Pedersoli rifle has a barrel with a 1:18 twist, which goes along with today’s general considerations for using heavier bullets. Let’s remember that the old standard rate of twist for the .45-70 was one turn in 22 inches and that was established while using the 405-grain bullets.

The next bullet given consideration was Lyman No. 457122, the famous 330-grain Gould hollowpoint. That one would still be light enough for comfortable shooting, but when I mentioned this to Steve Garbe, my thoughts of using the 330-grain bullet were quickly diminished. Steve told me about the time that he shot an elk with the 330 hollowpoint bullet and the bullet broke up without penetrating as deeply as he would have preferred. Even though I was rather sure that I’d be looking for adequate penetration on just a paper target, I wanted to use a bullet that should perform very well in almost any application.

Lyman No. 457124, the standard roundnose bullet, was also given some thought. That is probably the most historic bullet of all for the .45-70, being styled after the first 405-grain bullet for that cartridge. Even so, that bullet was passed on in favor of a bullet with greater weight.

The bullet finally settled on was Lyman’s No. 457193. My mould for this bullet is marked “Lyman Centennial Edition” and I’ve had it since 1978, when Lyman celebrated 100 years in the business. This bullet has a big flatnose; in the 1916 Winchester catalog a load with a similar bullet is shown and labeled the “.45-70 Marlin.” So, a good batch of those bullets were cast and one bullet was selected to be weighed. That slug balanced the scale at 424 grains. In general, Lyman No. 457193 is regarded as a 420-grain bullet, so perhaps my alloy is just a little softer.

For loading data, I quickly consulted Mike Venturino’s book, Shooting Buffalo Rifles of the Old West, and looked at what he tested this bullet with. Mike used five different powders for his testing with the 420-grain bullets, using 63 grains of powder with all of them. Let’s remember that Mike’s book came out 17 years ago and one thing he couldn’t do was test the load with Olde Eynsford powder. I quickly loaded just 10 rounds using 63½ grains of Olde Eynsford 1½ Fg under No. 457193, with the bullets sized to .457 inch and lubed with BPC lube from C. Sharps Arms. A .060 inch over-powder wad from John Walters completed the load and they were primed with Winchester standard large rifle primers.

With the rear sight adjusted just a little for windage, I tried another target, posted at 50 yards, with the black-powder loads. Two shots printed well for windage but they were low. So, the rear sight was raised one step and then . . . wow! Allen Cunniff was spotting my shots and my next shot was an X at 11:00 o’clock. I don’t remember the sequence of those shots now, but the final group was a very delightful 50 with two possible Xs. All of that shooting was done on just one target, so please excuse me for covering the two low holes with cartridges. The low holes were shot before the sight was raised when the picture of the rifle and target was taken.

The black-powder loading was not checked for velocity, but I would estimate that the bullet’s speed was about 1,250 feet per second.

The old Winchester Model 1886 was probably the smoothest operating of the lever-action rifles and Pedersoli’s version certainly follows in that tradition. This rifle was made available for testing and review by the Italian Firearms Group and they told me the suggested retail price for the 1886 Sporting Classic model is $1,995. The only thing I can add is that I like it very much. The one thing I would add to the rifle would be a Lyman #2 tang sight, that would finish this rifle in grand style.

For more information about this rifle and the other firearms they offer, go to: italianfirearmsgroup.com/pedersoli