New Loads for the .50-95 Winchester

feature By: Mike Nesbitt | June, 18

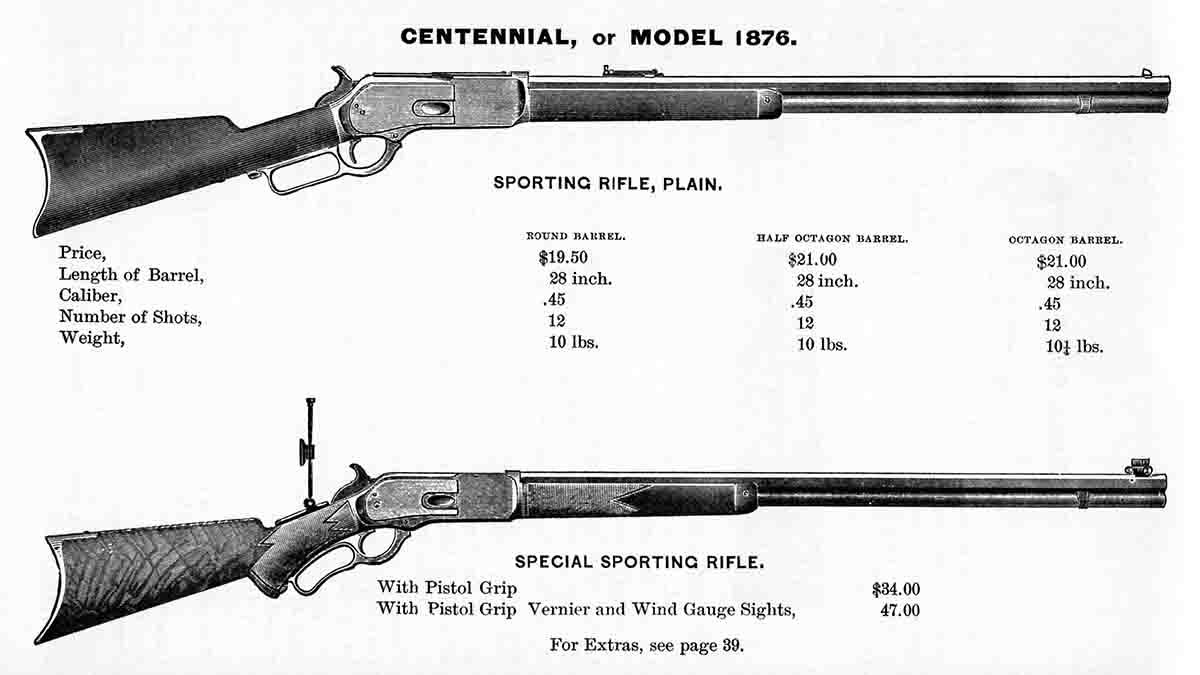

One of those ingredients is a very good modern copy of the Winchester Model 1876 rifle made by Uberti and at least one other maker. The Uberti was used for gathering the handload data. In general, handling and shooting the Uberti Model 1876 gave a different picture of the ’76 rifle than what was expected. I had previously thought it to would be too big, heavy and clumsy, perhaps with a picture in my mind of a frontiersman walking across the prairie, dragging his ’76 Winchester by the barrel. It is actually a fine rifle with a weight and balance that is quite nice to hold and aim.

The Uberti 1876 in .50-95 has a 28-inch barrel, the same barrel length as used for the company’s other ’76 calibers. That barrel

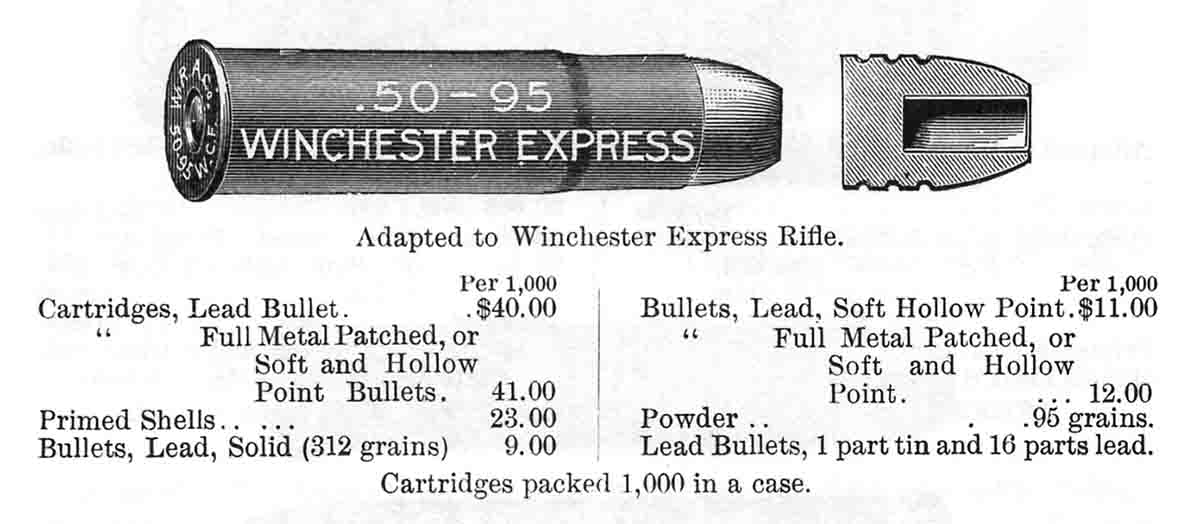

Another new component that wasn’t available when Mike tested loads for his book was Jamison’s .50-95 brass or ammunition. Jamison, now a division of CapTech International (CapTechIntl.com), has both new brass and loaded ammunition for all of the Winchester Model 1876 calibers, which certainly includes the .50-95. Jamison’s ammunition uses a 350-grain lead bullet over just enough smokeless powder to give it an advertised velocity of 1,300 fps; that’s a bit of a “cowboy” load, but it was the Cowboy Action shooters who made the old leverguns popular enough for this new ammunition to be made. All of the loading and shooting done for this update was done with either Jamison’s factory loaded ammunition or new Jamison brass.

So far, only the differences between Mike Venturino’s work and what will follow have been pointed out. There is no direct pathway from his testing to what was recently completed , even though I consider our

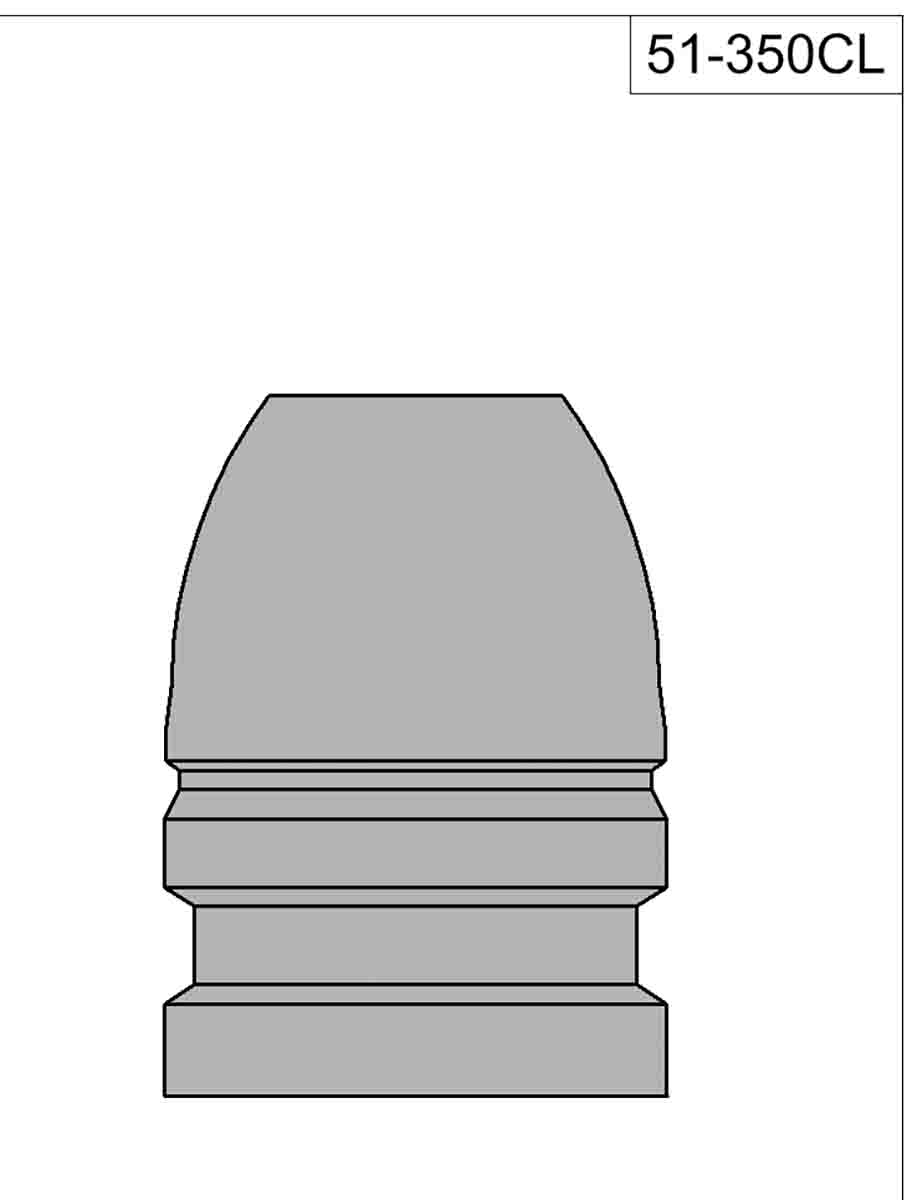

In terms of the bullets we used, Wayne Miller did the casting and loading for these tests, and his rifle was used for shooting. The handloads were topped off with 350-grain cast bullets from a Rapine mould made out of 20:1 (lead-to-tin) alloy, sized to .514 inch and lubed with SPG Lube. Going along very well with the new Uberti’s 1:48 rifling twist, the 350-grain bullet was used for all shooting.

Rapine moulds are no longer available, so a little more about the bullets should be shared. For shooters who want a good bullet for Uberti rifles in .50-95, Accurate Molds No. 51-350CL mould is highly recommended. This bullet has the proper nose shape and distance from the crimp groove for positive feeding from the magazine in a lever-action .50-95 Model 1876. Visit Accurate Molds (accuratemolds.com) to see another bullet mould for the .50-95, No. 51-350C. The only difference between these two bullets is that No. 51-350CL is slightly longer with a larger lube groove and designed more with the black powder shooter in mind.

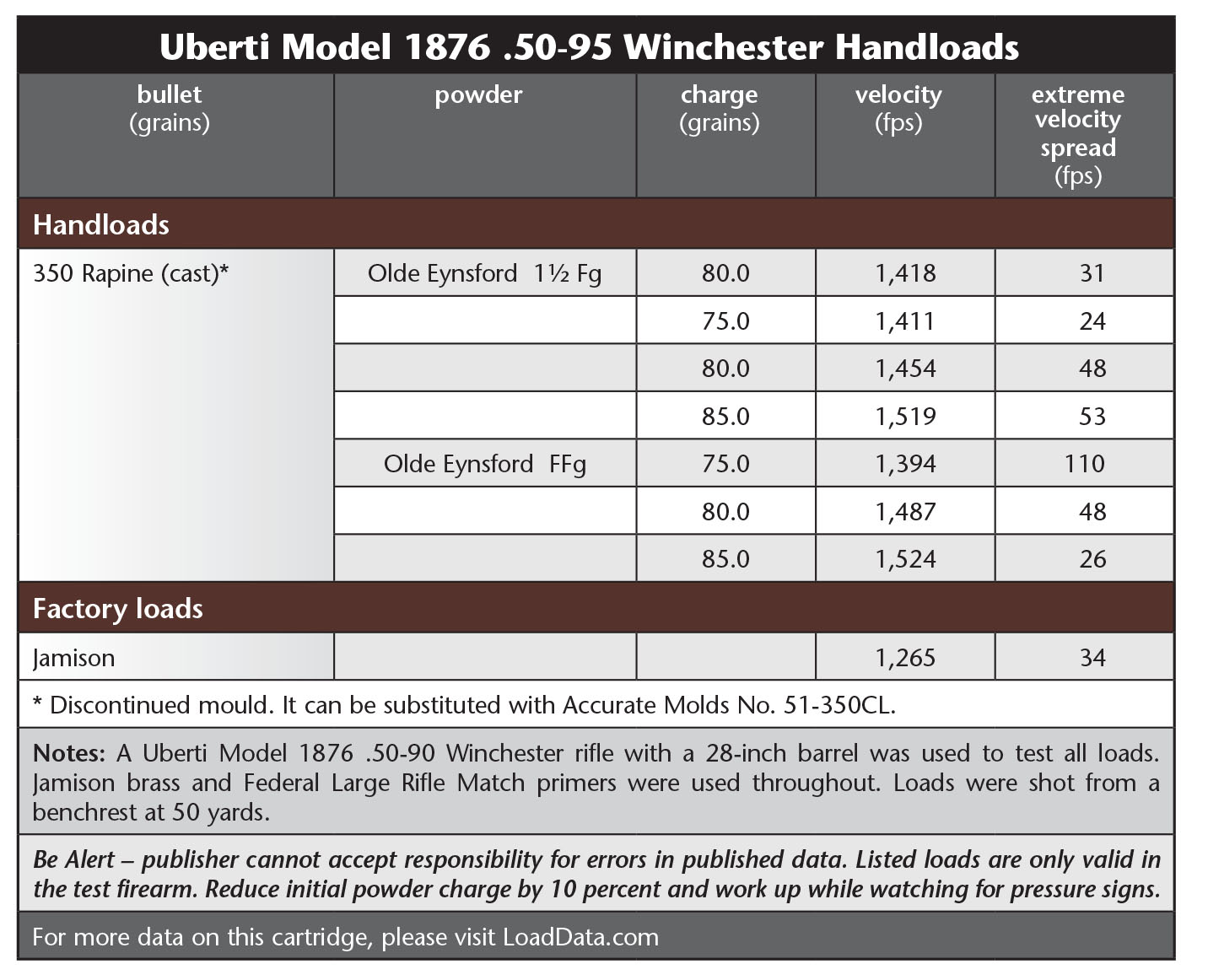

All handloads used Jamison brass, as already mentioned, and were primed with Federal Large Rifle Match primers. The powder charge was always dropped into the primed cases through a 24-inch drop tube and then topped with a .030-inch Walters veggie wad. Loads were shot from a benchrest at only 50 yards. Our shooting quickly showed that the rifle’s front sight was too low, so consequently our groups went a bit high. For chronographing, five shots per load we fired, so the test results might show a rather small sample.

The rifle was cleaned after each five-shot group, so the shooting with each loading began with a clean barrel. This rifle was an out-of-the box Uberti, using the sights that came on it as well as the trigger pull. The trigger pull was on the stiff side, especially to a shooter who feels more at home with set triggers.

Our shooting went well with only a couple of curious moments. One question was why there was an extreme velocity spread of 110 fps for five shots loaded with 75 grains of Olde Eynsford FFg? It does suggest that a larger sample size (more shots fired) would be helpful. We must accept that a velocity spread of 110 fps is nontypical.

Also, when comparing the velocities of the 75-grain loads, only one of the shots fired with 1½ Fg powder fell below 1,400 fps, down just to 1,399 fps. On the other hand, three of the five shots fired with 75 grains of Olde Eynsford FFg powder were recorded as being below 1,400 fps and, as shown in the listing of handloads, the average velocity was lower with FFg powder, but only in the 75-grain handloads.In general, loads with the 85-grain powder charges seemed to make the rifle almost come alive, and those are loads that should interest big-game hunters the most. It was the 80- and 85-grain loads that gave the best groups. At the same time, changes to the sights were discussed, which should improve the rifle’s accuracy all the way around. With some improvement to the sights, combined with the 85-grain loads, the .50-95 certainly becomes a serious contender for putting meat on the table. Given the prices of original Model 1876 rifles in .50-95, the Uberti ’76 is a well-made and accurate alternative for the black powder cartridge hunter.