Seems Like Old Times

Hunting in the Timber with a .45-70

feature By: Harvey Pennington | June, 18

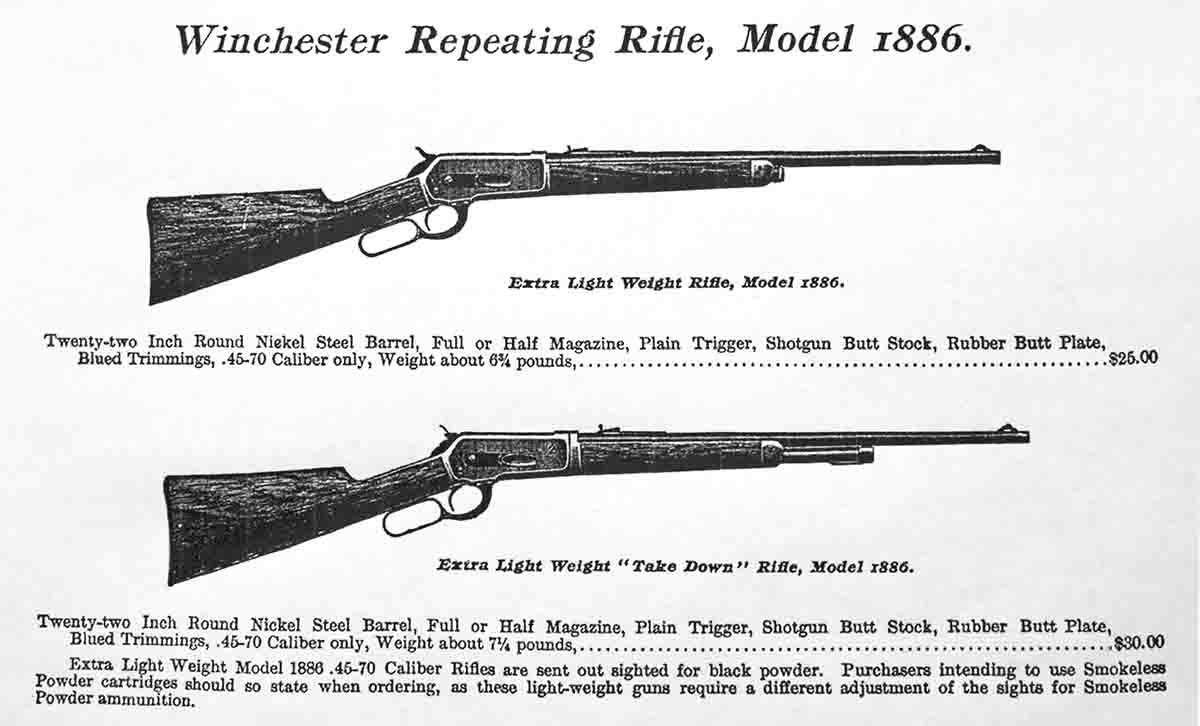

The old .45-70 always seemed to lift my spirits. It was manufactured in 1903 and to quote from the Winchester catalog of that year, its official designation was an “Extra Light Weight ‘Take Down’ Rifle, Model 1886.” The price back then was $30.

At some point in the past, a Winchester recoil pad with a patent date of 1922 was added to the buttstock. The job was nicely done, and the alteration did not bother me in the least.

I bought the rifle only four or five years ago, and it quickly became my favorite black powder cartridge rifle for hunting. I have taken three deer and one antelope with it, using three different loads: A smokeless load using an RCBS 45-405-FN gas-check bullet with 44 grains of IMR-3031 for 1,616 fps; a load for deer and antelope using a 335-grain Lyman No. 457122 Gould hollowpoint bullet with 77 grains of Swiss 1½ Fg black powder that generates 1,446 fps; one deer cartridge using Lyman No. 457193 with black powder. I’ll describe the last load next. All shots were well placed, and the farthest any of those animals ran after being hit was one deer that traveled no more than 15 feet.

Of course, my experience with the cartridge is comparatively limited, but those who were around when it was more commonly used also had great respect for both the cartridge and the Winchester Model 1886. One of those was Elmer Keith (1899-1984), the well-known hunter, guide and author. In his 1946 book, Keith’s Rifles for Large Game, Mr. Keith stated, “The .45-70 Government is one of our oldest loads and is still a good killer at close ranges. With either the 405-grain soft-point or the old black powder 500-grain bullet it has proved a far better killer on our larger species than any .30-caliber, including the .300 Magnum. Winchester made a solid-frame Model 86 for the .45-70 cartridge. Its lightweight, 22-inch nickel steel barrel, shotgun buttstock, receiver peep and ivory or gold front sight combined to make it a handy and powerful timber rifle . . . For deer and elk in the timber, at less than 100 yards, I do not know of a more reliable rifle and load, and it is also good on the big bears.”

Although I have had some luck with the .45-70 on deer and antelope, efforts to collect an elk with it have not panned out. The old rifle was taken on a backpacking hunt for elk in the Medicine Bow Mountains of

The prepared loads for the elk hunt would now be used for deer season and were very close to the black powder factory loads once offered by Winchester and Marlin using a 405-grain bullet. The new handloads consisted of .45-70 Winchester brass, CCI 250 primers and a powder charge with 67 grains of Swiss 1½ Fg. A card wad cut from an orange juice carton was inserted on top of the powder. A Lyman No. 457193 cast bullet that I had pan-lubed with a homemade mixture was seated. The bullets were used unsized and weighed 416 grains when cast of 1:16 alloy. Overall length of the loaded cartridge was 2.590 inches. When seated, the powder charge was compressed about 3⁄16 inch.

This .45-70 load using a 405-grain bullet chronographed an average of 1,262 fps, nearly identical to the 1,286 fps black powder factory load that Winchester published in its 1903 catalog. It gave three-shot groups of about 3 inches at 100 yards. Because this was a hunting load, I did not wipe or blow through the barrel between shots.

In the early days, factories had a wide assortment of black powder loads for the .45-70 with bullet weights varying from 330 grains all the way up to 500

In the process of doing some research, it was surprising to note that Winchester’s factory 405-grain, lead-alloy bullet was not the flatnosed Ideal (later Lyman) bullet No. 457193. That bullet was instead originally designed for Marlin’s .45-70. The 405-grain bullet factory loaded by Winchester was actually a roundnose design, Ideal/Lyman No. 457124 that the old Ideal Handbook referred to as “…usually used in the Springfield carbine. It is also an excellent cartridge for elk, moose, and bear.” Winchester and Marlin each used a tin-to-lead 1:16 alloy for those bullets.

Moulds for both No. 457193 and 457124 are still offered by Lyman. I have only the flatnose No. 457193, and it has shallower, rounded lube grooves that are associated with cast bullets used with smokeless powder. Illustrations of the original Ideal No. 457193 show that it had deeper, “squared” lube grooves that I would much rather have for black powder

I have always preferred flatnose, cast bullets for hunting because they impart greater initial impact, producing a larger entrance hole and wound channel than roundnose, cast bullets. Also, I have always avoided the use of roundnose bullets in rifles with tubular magazines because the rifle’s recoil may cause the point of a bullet in the magazine to detonate the primer in the cartridge ahead of it.

So, when using my Model 1886 .45-70, I will stick with the Lyman No. 457193 and hope that Lyman will see fit to re-introduce a black powder design of that bullet with square grooves. Of course, there are custom mould-makers today that could copy the older design of the 457193, and I’m seriously considering having one made.

The Kentucky deer season had only a couple of days left, and deer were proving difficult to locate. To further complicate matters, there was a strong wind blowing as I stepped outside that morning to go hunting.

A likely place to sit on the hillside was located about 25 yards above the trail that ran along a creek in the bottom of the steep hollow. Facing the trail, I straddled the trunk of a downed tree, leaning against its overturned root system. It was fairly comfortable, and the wind that was blowing hard on the ridges that early morning was not even noticeable down in the hollow.

Perhaps an hour had passed when a doe startled me as it came running down the trail with a young buck following close behind. The hammer was silently cocked on the .45-70, and was slowly raised to my shoulder. Without noticeably breaking stride, the doe made a quick left turn off the trail and ran up the steep hillside, passing just a few yards to my right. But, when the buck got to the point where the doe had left the trail, it turned in the direction the doe had taken, then paused. At this point, the buck’s head and neck were hidden behind the trunk of a large oak tree, but I had a clear view of the right side of its body. I decided to take the shot. There were many trees in the area, and if it decided to follow the doe, the opportunity would probably be lost.

I was only about 30 yards from the buck and took the shot “offhand.” This would be the correct description of the shooting position taken, even though I was still sitting on and straddling the trunk of the downed tree at the time. The brass face of the homemade front sight was easy to see as I aimed behind its shoulder. I squeezed the trigger, and the low-pitched “boom” of the .45-70 broke the morning stillness in the hollow. The smoke of the black powder charge instantly obscured the view of the deer, but then began to

It is truly special to take a black powder cartridge rifle on a hunt. There is a kind of connection, a “relation-back” if you will, to those who hunted with such rifles in the late 1800s and early 1900s – a time when hunters relied on cast bullets, black powder and iron sights.

Also, just as in those olden days, the lower velocity and higher trajectory of black powder loads still challenge hunters to get much closer to game than is necessary for those who use today’s popular high-velocity, scope-sighted rifles. I like that challenge; especially when it is successfully met using a 114-year-old rifle that is still as capable of fulfilling its task as it was the day it left the Winchester factory.

REFERENCES:

1. Winchester catalogue, Number 70 (1903); Reprint by CORNELL PUBLICATIONS.

2. Ideal Handbook, Number 15

3. Ideal Handbook, Number 34

4. Marlin Firearms Co. Catalogue (circa 1900)

5. Keith’s Rifles for Large Game (1946) Standard Publications Incorporated, Huntington, West Virginia.

While considering black powder loads for elk, I experimented with a 500-grain Lyman No. 457125 bullet. This mould was purchased about 1980. Early Winchester catalogs stated that its .45-70 load using the 500-grain bullet was suitable for use in the 1886 Winchester, as well as in the Springfield and the Winchester Single Shot Model 1885. From research, it was confirmed that the Ideal No. 457125 was standard for those loads, but the forward portion or nose of my Lyman bullet was found to have a diameter of .456 to .457 inch. This was simply too large to allow a loaded cartridge to chamber as it should in my Model 1886 rifle, unless the bullet was seated so that the overall length of the loaded cartridge was about 2.600 inches. when loaded to that overall length, however, the powder capacity of the case was reduced so that it would hold only about 55 grains of Swiss 1½ Fg black powder. Even then, the powder charge would have to be compressed about 3⁄16 inch. At that point, the idea of using a load with that bullet was abandoned.

Illustrations from the 1903 Winchester Catalog plainly show that its 500-grain bullet was seated out considerably farther than I was able to seat mine, yet the 500-grain load was recommended for use in the Model 1886 rifle. That makes me believe that the dimensions of my particular mould are simply oversized. I think that with a mould of proper dimensions, the bullet should be able to be seated in the same position as in the illustration and use a charge of black powder close to the 70 grains used in the old Winchester loads.