The Wyoming Schuetzen Union's "Center Shot"

The Leech Cup - Lost . . . and Found

column By: Jim Foral | November, 20

The Irish Rifle Team was fresh from the unexpected 1873 Long Range victory over their British counterparts for the Elcho Shield and savoring their claim to the Championship of the British Empire. They looked across the Atlantic Ocean for their next conquest and to exert their newly found dominance. That November, the Irish club issued a public notice in the New York Herald, extending a challenge to any American rifle club to a meet on their club’s own soil, and one corresponding to the conditions adhering to the Elcho Shield rules on an agreed upon future date.

The 67 members of New York’s Amateur Rifle Club cheerfully accepted the challenge. There was no home court, or range, advantage. Indeed, there was no rifle range beyond 500 yards in the U.S. That no club member had ever fired a shot at the Elcho Shield distances of 800, 900, and 1,000 yards, was seen as something a year’s diligent practice should overcome. The fact that there was not a specimen of a 1,000-yard capable rifle in the country didn’t seem to deter the Amateur Rifle Club.

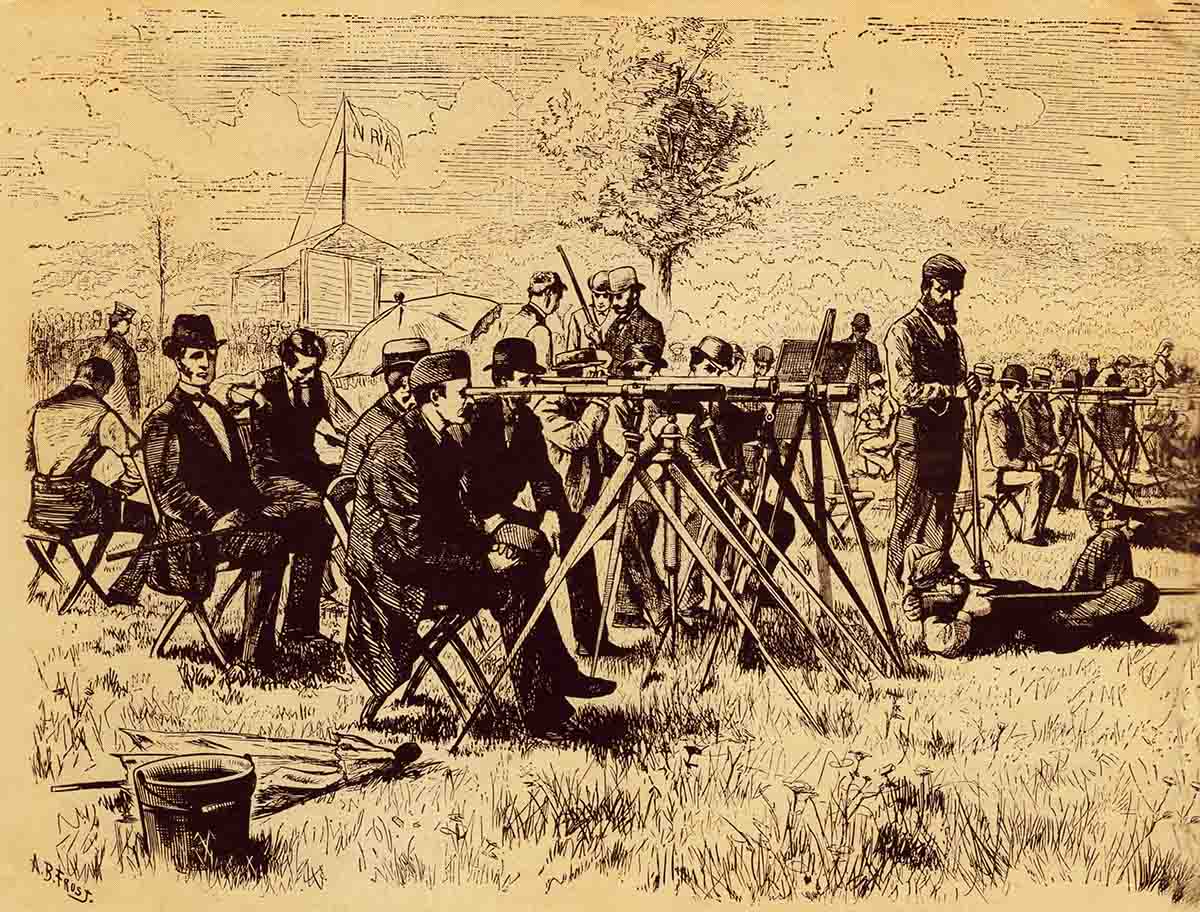

Straightaway, the great Creedmoor Range was improved and generally made presentable for the foreign visitors. It was relandscaped to accommodate a 1,000-yard berm with a summit high enough to catch any reasonable miss. A telegraph was added to communicate instantly between firing points and the butts.

Without delay, Remington and Sharps built suitable 1,000-yard rifles on their own existing actions that were hoped to shoot alongside the Rigby and Metford rifles used by the Irish. Dutifully, the press fulfilled its journalistic objective. Regular newspaper and sporting journal coverage kept the public updated and engendered interest in the impending match, promoting it into the country’s big news event.

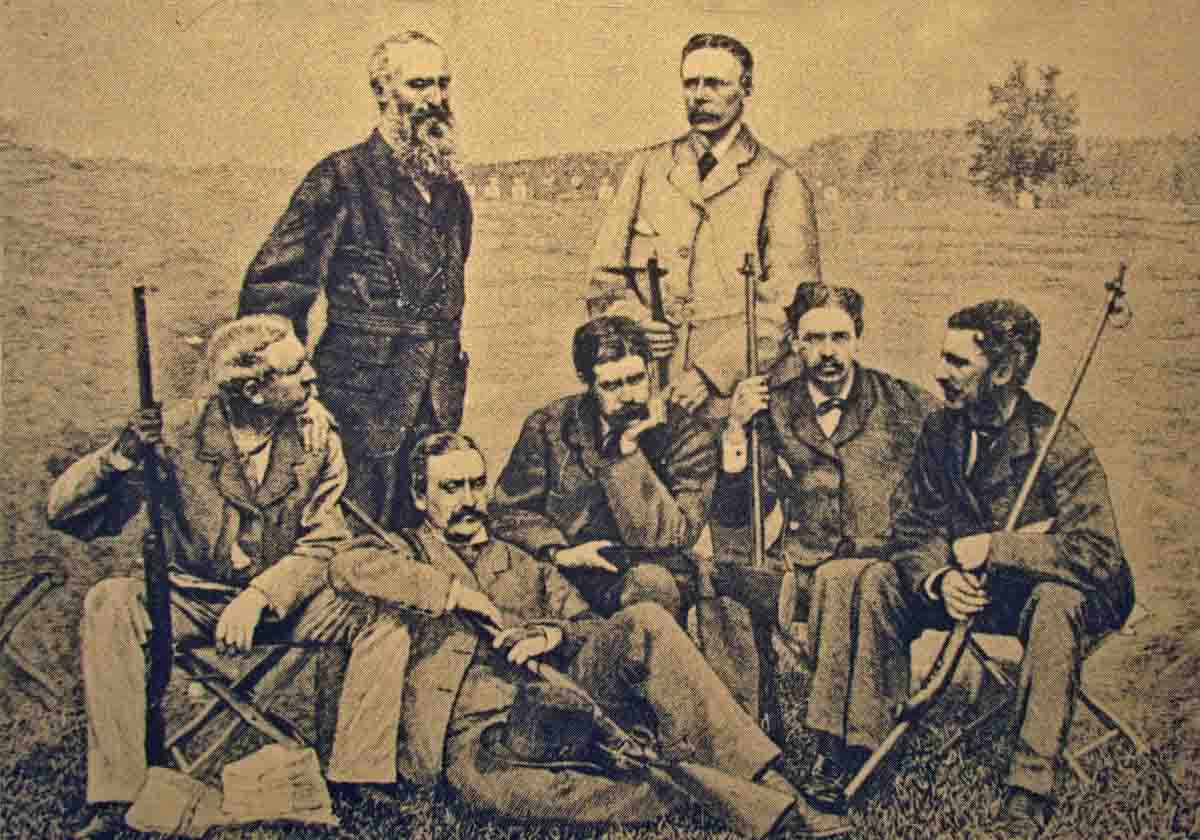

The American team was selected from tryouts and was also based on recent standings of applicants from the Amateur Rifle Club. The Irish Rifle Team arrived in New York on September 15, for the September 26, 1874, contest.

In terms of a spectacular, “against all odds” triumph in a sporting event, the 1874 American win over the Irish was comparable only to the finish of the 1980 Olympic hockey event, rightly termed “The Miracle on Ice” and matched it for the resultant national pride evoked.

Accompanying the Irish team to the United States was its Captain, Major Arthur Blannerhasset Leech of Dublin, a capable individual with the right stuff to competently shepherd a party across an ocean. It was Leech’s name that had appeared on the signature line of the New York Herald challenge, and it is strongly suspected that the entire idea and plan for the match originated with him. Leech was the captain not only of the globe-trotting Irish Rifle Team, but also of the Irish Rifle Club, a national organization which boasted several thousand members. Major Leech was the man who had been instrumental in changing the minds of the hardheaded officials that had excluded Ireland from being allowed to compete for the Elcho Shield. Prior to 1865, and Leech’s taking on that monumental challenge, this had not been possible. Major Leech was a model of leadership, and a worthy and adept representative not only of the rifle team he escorted, but also of the homeland that had entrusted him with the duty.

The Irish Rifle Club came to America bearing gifts. In the spirit of international friendship and camaraderie, Major Leech had commissioned a tastefully wrought trophy in the form of a tankard, though one journalist used the term “vase” in his description. Another termed the prize a “cup.” Whatever one chose to call it, the prize was artfully constructed of pure Irish silver, and made by the best silversmith on the Emerald Isle. Upon its hinged cover was an ornate representation of an ancient castle in ruins. The trophy’s 1874 value was put at $600.00.

On the occasion when Major Leech presented the “cup” to the Amateur Rifle Club, he also stated his intention that the annual contest for this trophy would be perpetuated as an American long-range match on the regular Creedmoor schedule as a memorial to the friendship between countries at their 1874 contest. He also hoped that long-range shooting would be encouraged thereby. Major Leech’s gift to the American riflemen bore a conspicuous inscription to this effect, directly restating his intention: “Presented for Competition to the Riflemen of America.” More than this, he recommended the trophy would be kept in the possession of each annual winner until the next match.

The first match was to be held in late 1874, while Leech was still in the country. He had taken advantage of his time in the U.S. by taking an extended hunting trip to points west and south into the wilds of the American frontier. Collecting specimens of the still numerous North American bison was of particular interest. On November 12, Major Leech was presented a gold medal, engraved by Tiffany and Company, from the members of the Amateur Rifle Club. On that occasion, it was officially decreed that the cup donated by Major Leech would thereafter be known as, “The Leech Cup.” In December, what was to be the first Leech Cup Match was cancelled “owing to the lateness of the season.”

The inaugural 1875 Leech Cup Match went to John Bodine, who would go on to national and international prominence as a long-distance marksman, and on whom was hung the nickname “Old Reliable,” for his repeated ability to pull off a match-winning clutch shot. Bodine’s 1874 teammate, Judge Henry A. Gildersleeve, won the cup in the Centennial year of 1876. Gildersleeve, apart from being a prominent winning rifleman, was a Civil War veteran who fought at Gettysburg and rode with General William Sherman on his march through Georgia.

Two other men with recognizable names yet, H. S. Jewell and Frank Hyde won the Leech Cup in 1877 and 1878, respectively. Hyde, 23 years later, proved he could still shoot by winning the All Comers Match at Sea Girt in 1901.

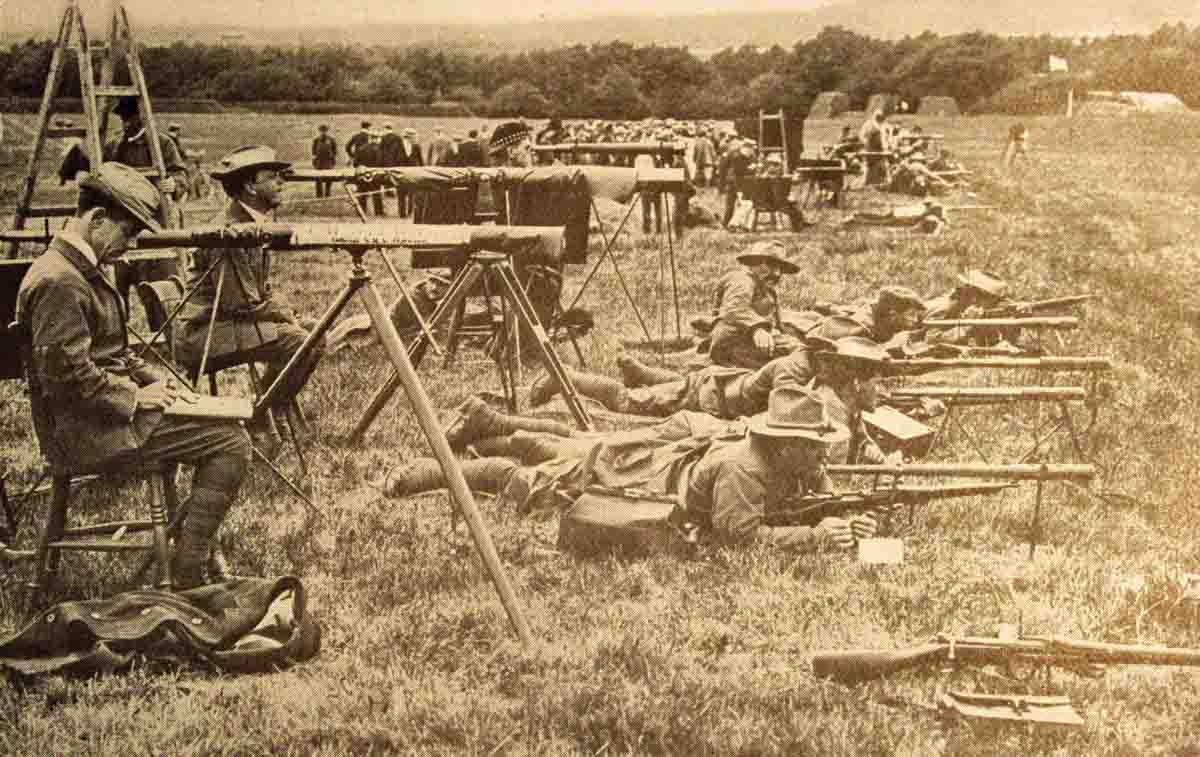

The Leech Cup competition was suspended in 1882, due to the lethargy within the NRA and wasn’t reinstated for 20 years, at which time a new generation of crack military rifle shooters had emerged. Sgt. William F. Leushner, a Palma Team veteran won it in 1902, the year of the Leech Cup’s reincarnation. Charles B. Winder, 29 years of age and a member of the 1903 U.S. Palma Team victorious at Bisley, England, used his competition Krag to win the Leech Cup that same year. Winder’s teammate at Bisley, New York, Guardsman George E. Cook, took the Leech Cup in 1904.

A nameplate was added to the cup for each year’s winner. At that time, only one man could boast that his name was on the cup more than once. William H. Richard of Connecticut won it in 1905, 1914, and again in 1916. Kellogg K. V. Casey, who E. C. Crossman once labeled “the best shot ever to face a target,” was a multiple Palma Team veteran and won the Leech Cup in 1908, the same year he won a gold medal at the London Olympics.

Along with the other trophies to be won, the Leech Cup was on display at the 1913 National Matches held at Camp Perry, and was won that year by Capt. George W. Chesley of New Haven, Connecticut. Capt. Chesley was one of the best contemporary marksmen and was well-known in national competition. He had been a member of the 1912 Palma Team who fit right in with the other standout teammates; Bill Tewes, Jim Keogh, John Hession, and K. K. V. Casey. After the Leech Cup event, Chesley refused to accept the prize. NRA policy demanded that the winner put up a substantial bond to guarantee its safekeeping and return for the next matches; the same rigid requirement they had for any other valuable trophy held temporarily. For whatever reasons he may have had, Chesley didn’t want or accept the responsibility.

The National Matches in the “teens” were held but sporadically and the next events were held in 1915, at Black Point, Florida. No one was able to explain why the Leech Cup was not on hand to be viewed in its splendor, and when Sgt. J. M. Thomas of the 3rd U.S. Cavalry finished in first place in the 800-, 900-, and 1,000-yard contest, there was no Leech Cup for him to pose with. It was thought, since it’s always bad form to broadcast details of touchy subjects, that the 1915 Matches were the first occasion that the Leech Cup had been missed.

The responsibility in 1913, for boxing the cup for its transport back to Washington may not have been delegated. Presumably, everyone responsible had supposed that the job had been done by someone else. In any event, the trophy had vanished, but at least Chesley could be crossed off the list of suspects. When Captain W. H. Richard placed first in the 1916 Leech Cup Match, there was still no cup, nor any clue as to its whereabouts.

When Brigadier General Fred H. Phillips Sr. became Secretary of the National Rifle Association in 1916, one of his first orders of business was to initiate an aggressive search to locate the missing Leech Cup. By then the trail was a cold one. The cup had left no scent or tracks, but B. G. Phillips was a persistent and tenacious sleuth. He began his investigation by quietly writing past winners and others that might have known something, anything. Beyond that, he got the word out and appealed to the NRA membership to be watchful. In a 1921 Arms and the Man column, he made suggestions to the readers where to begin looking. “It may have been taken away from the 1913 Matches by mistake by some winning rifle or pistol team,” he wrote, and encouraged the members to visually comb the trophy cabinets of National Guard armories and similar places where military men congregated, and where it could be innocently hiding in plain sight. It may have been in the hands of an individual competitor in a private trophy case or that of a gun club unaware of its significance. Phillips fully expected the trophy to be found intact and in its original form. He and other NRA officials thought it would be improbable that something so magnificent would be scrapped for its silver content, but no one discounted that possibility.

The people were urged to remain attentive to this NRA need and to keep their eyes open. It wasn’t a long shot that it could be found stowed away in the collection of a trophy hoarder, or in the inventory of a dealer in antiques. Phillips also included with his essay the necessary picture of the Leech Cup so people would recognize it should they blunder into it in their travels. As the years went by, recovering the lost Leech Cup seemed to be more and more hopeless. Each of the few leads was investigated as best they could have been, but inevitably they wound up at the same dead end. Keeping the collective fingers of NRA officials crossed hadn’t helped, nor did invoking the favor of Saint Anthony of Padua, patron saint of lost things, but it may have made them feel as if they did something. That bigger and more precious objects had disappeared without a trace and little could be done about it was the only comforting rationalization. Their last recourse, pinning all of their hopes on dumb luck, happened to be the easiest, and in the end, resulted in their only success.

The man who discovered, or more correctly, was led to the missing prize was also the author of a mid-1927 public notice of its recovery from parts unknown. Al Blanco, whose byline was a familiar one to American Rifleman readers, was not particularly forthcoming with the details about the cup’s recovery, and suggested that its actual location and other specifics would not be pried loose from him. If he was privy to how it came to be where it was, he kept that also to himself. He presented his rationale in such a way that would seem to discourage the unwanted inquiry of the idly curious. He had only this to say: “There are good and sufficient reasons why I cannot divulge the source from which I received the cup.”

Al Blanco had one more secret. The fictitious “Al Blanco” was the nom de plume used by prominent industry personality Frank J. Kahrs, who used his own name, or his pseudonym, when his own subjective rules indicated that he did so. Kahrs was an active smallbore competitor and was instrumental in its organization on both national and international levels. He also served as an associate editor with Arms and the Man. In 1915, Kahrs took a position in the advertising department of Remington Arms, and was an effective and competent ambassador for the firm. His was a recognizable name in the magazines of the era, as was Al Blanco’s.

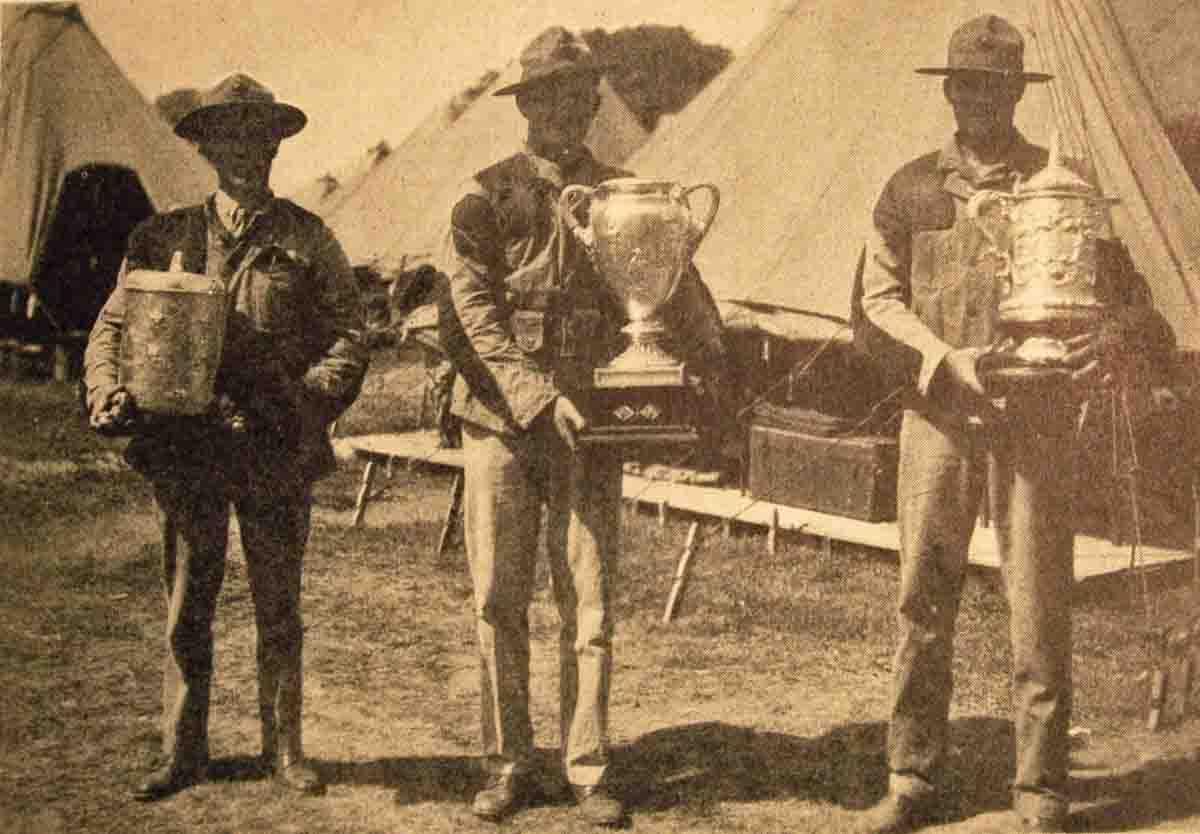

The Leech Cup was found in plenty of time for it to be presented to the NRA for future safekeeping. At the Camp Perry National Matches in 1927, the cup again saw the light of day when it was awarded to Marine PFC R. F. Seitzinger, that year’s winner from a field of 200 and two hopefuls. Understandably, he was allowed to hold it for as long as it took to snap the photograph that appeared in the October, 1927, issue of the American Rifleman.

With the Leech Cup back into possession, those in charge of preserving that status could exhale thankfully, and find comfort and absolution with the proverb “All’s well that ends well.”

.jpg)

.jpg)