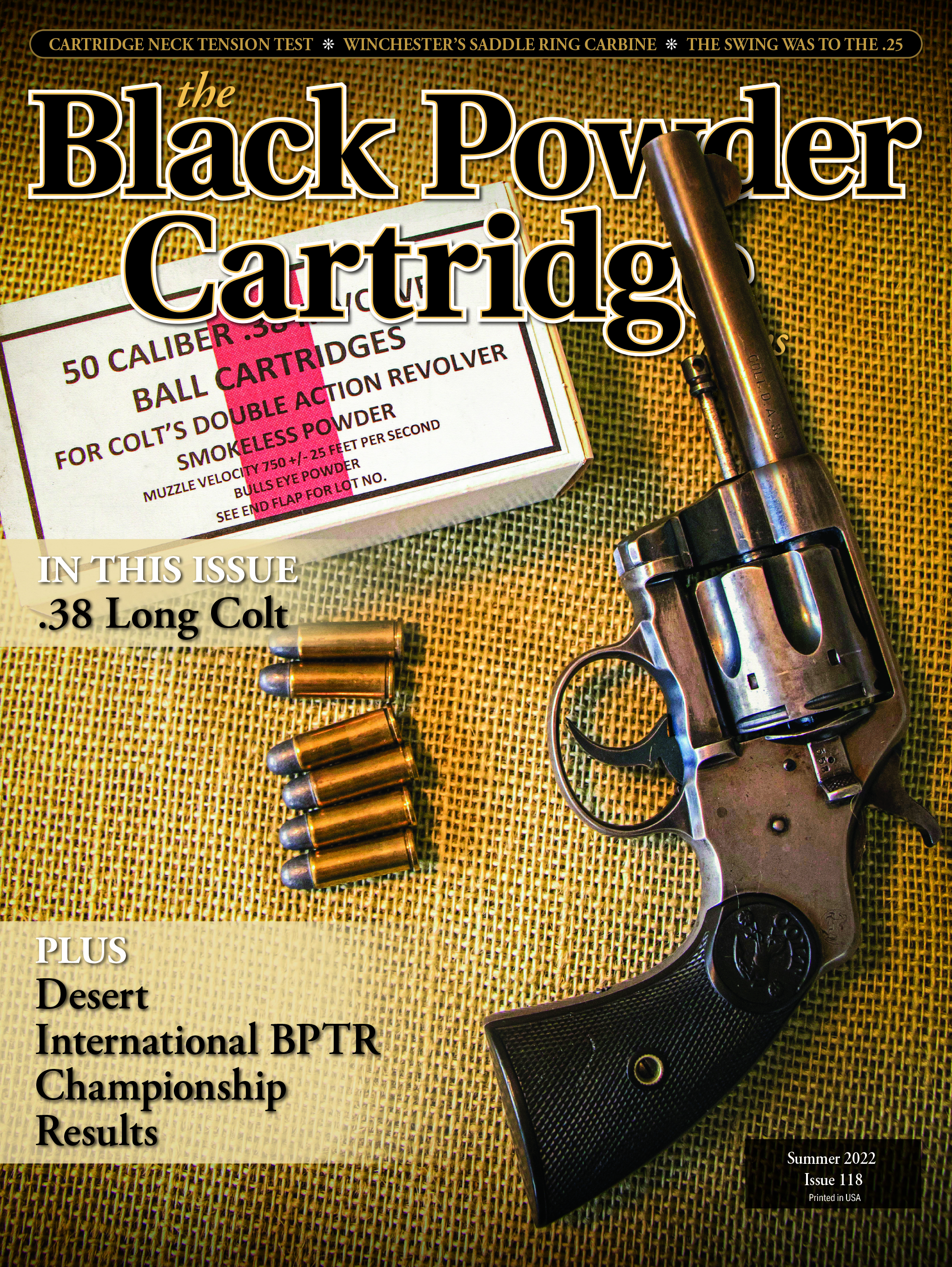

The Wyoming Schuetzen Union’s “Center Shot”

The Swing Was to the .25

column By: Jim Foral | June, 22

If a craze for caliber .25 was destined to have an end after its necessary span of a middle, it logically follows that it must have a beginning. In the case of the .25 caliber, this required breaking unfurrowed ground. There was no .25-caliber bore in the 1880s, America. To Francis J. Rabbeth of Boston, this was an obstacle to overcome if his objective to bridge the caliber gap between .22 and .28 was to be realized. An origination, in this case, needed to precede the beginning.

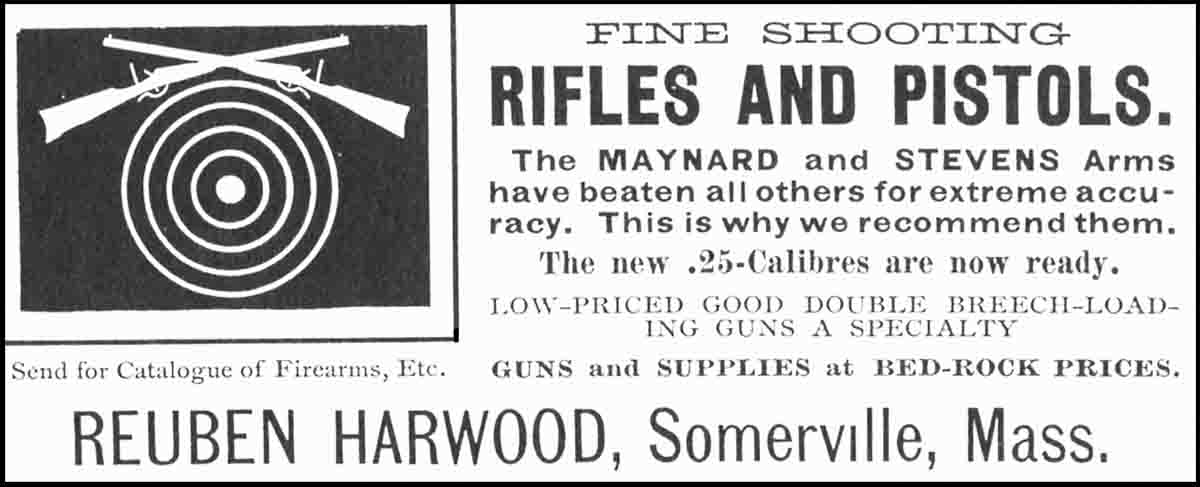

Rabbeth saw some merit in what he had done and felt that such an item would benefit his fellow riflemen. In 1888, and in the usual journals, Rabbeth agitated for the adoption of such a cartridge, and in 1889, and engendered the considerable following which sometimes precedes a craze. He gained the vocal and critically-influential support of well-known gun shop proprietor, rifleman, and far-flung magazine contributor, Reuben Harwood of Somerville, Massachusetts, who also chimed in.

“There is also another cartridge, the new .25 caliber center-fire that is now being made by these people (Union Metallic Cartridge Co.) and the writer saw a target a few days since at the Massachusetts Arms company’s factory of seven shots at 200 yards, all of which were in a two-inch circle.” The cartridge was then known as .25-20-85. Harwood was then bold enough to declare, “The .25 caliber is here and has come to stay… long may it wave.” The craze was off and running.

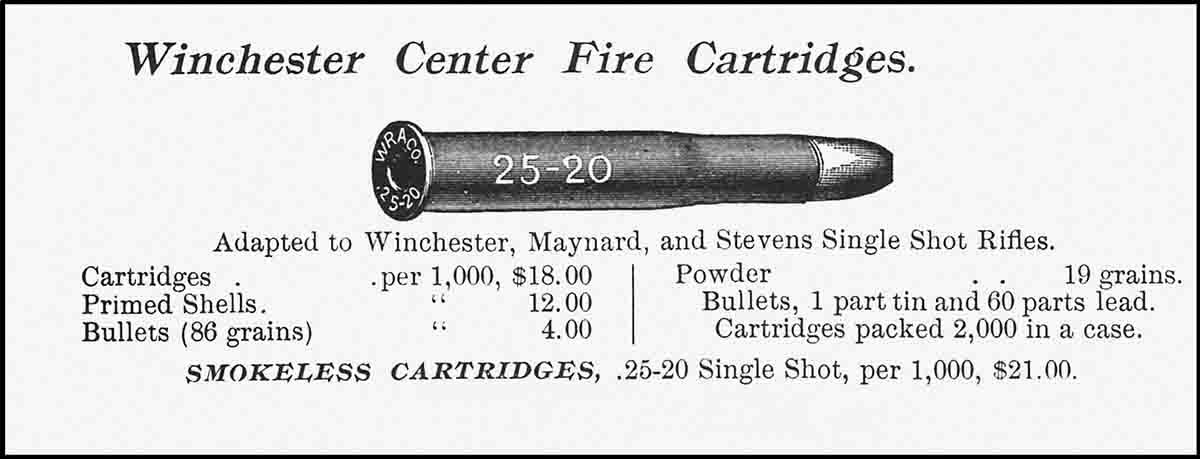

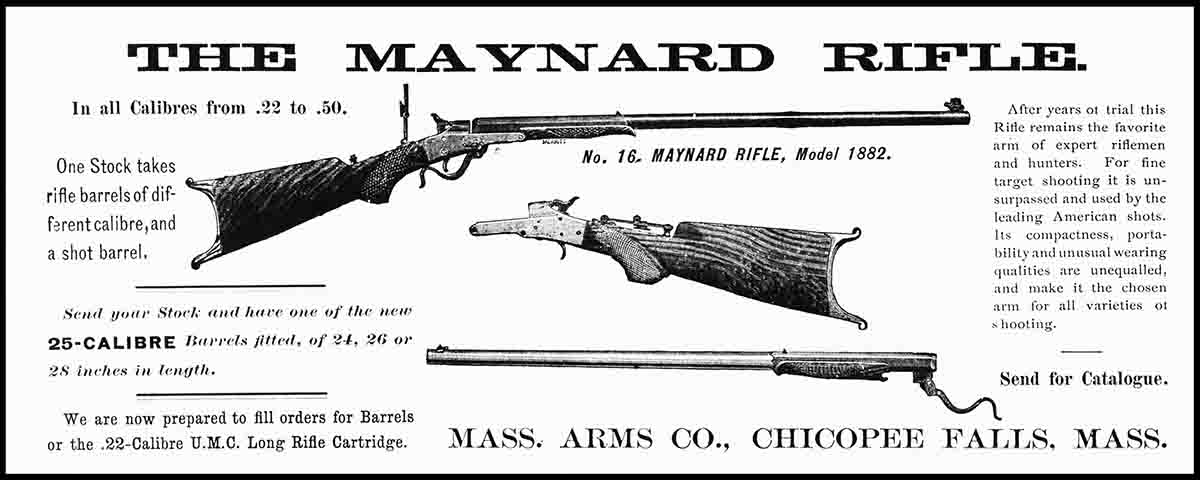

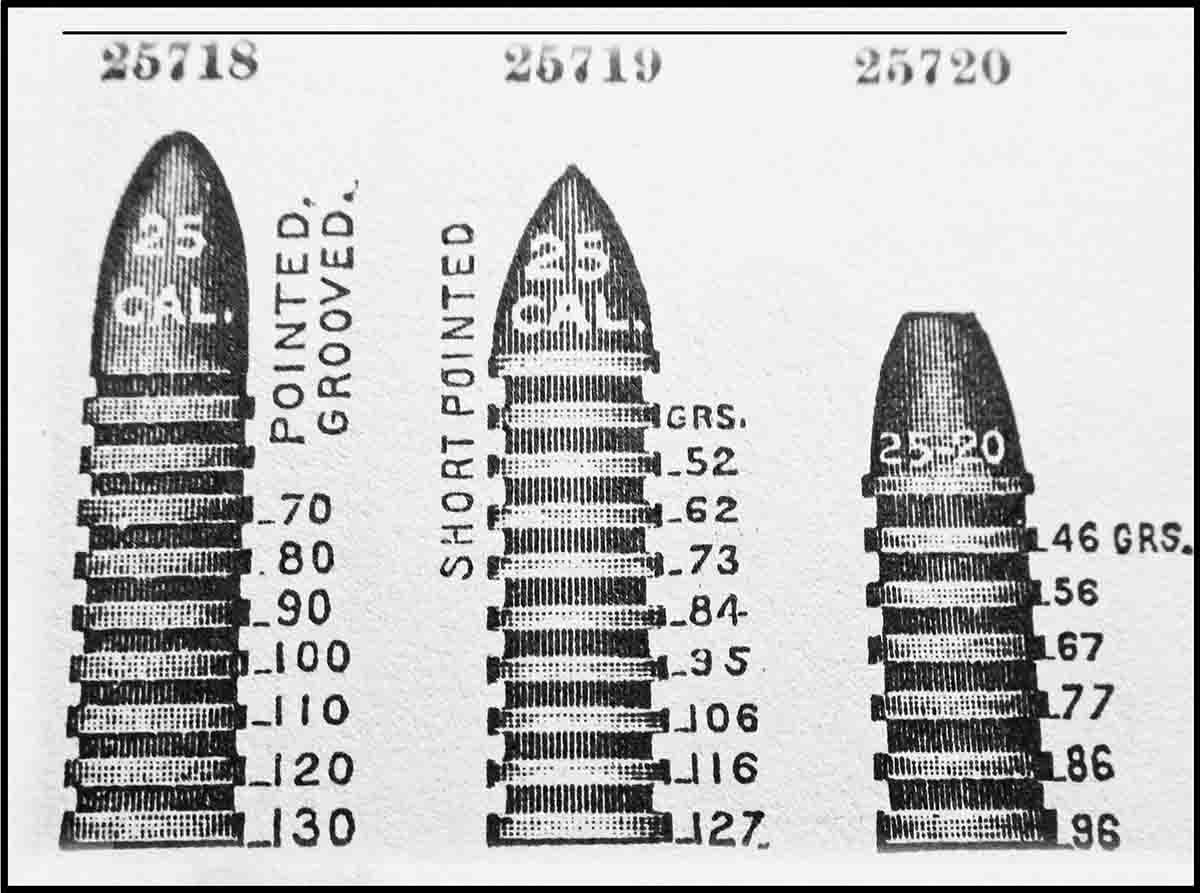

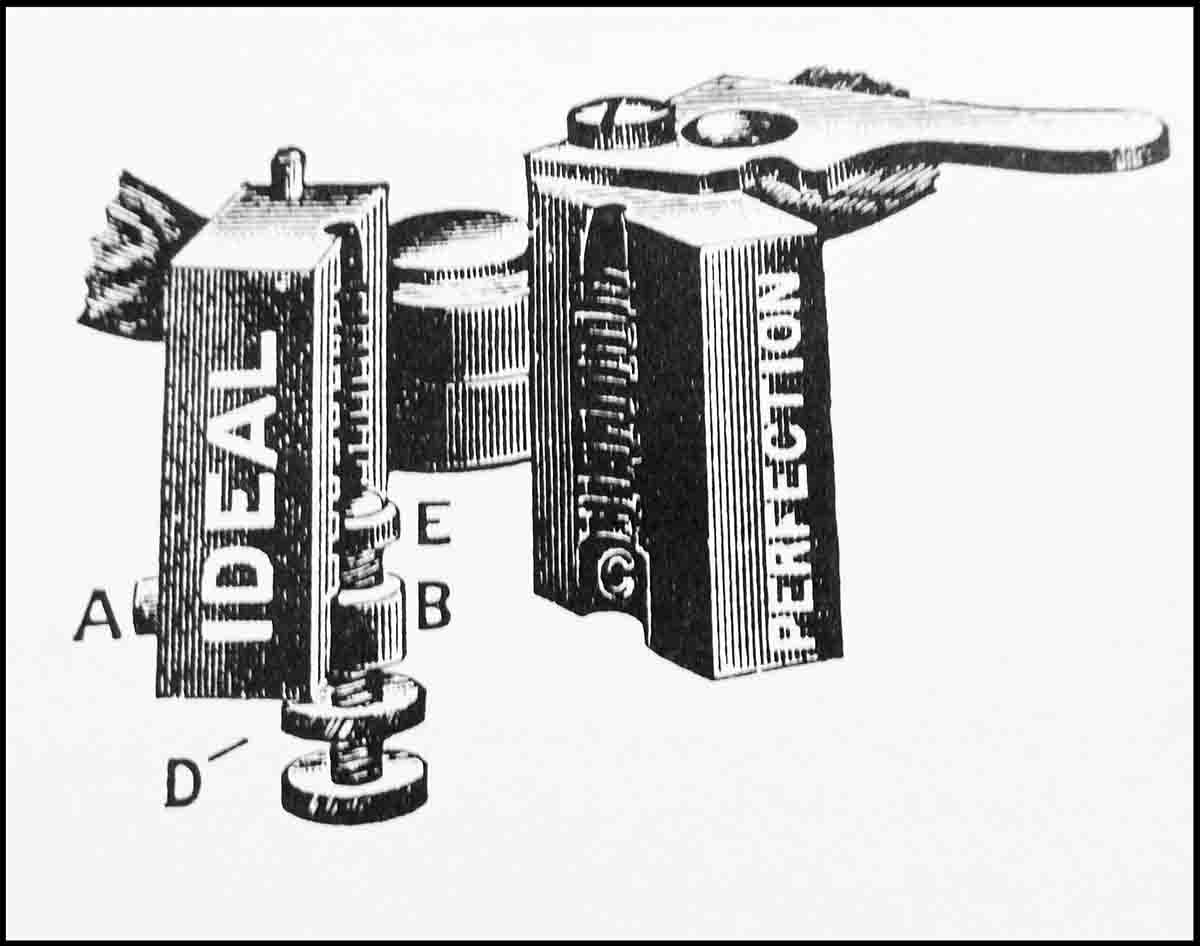

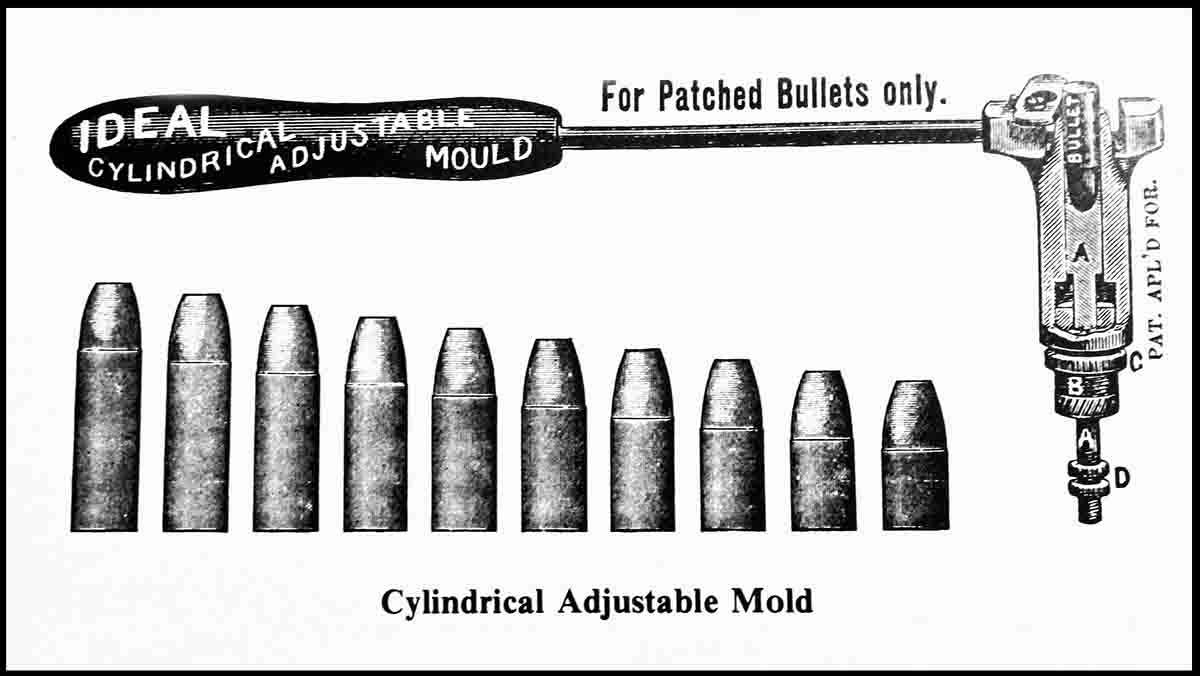

Straightaway, the arms industry responded. They all prospered from the resulting boon. By late October 1889, Reuben Harwood, whose shop was becoming known as the Boston-based headquarters for the marksmanship-mad and all things .25 caliber, was able to nationally advertise that “the new .25 calibers are now ready.” At the same time, the Massachusetts Arms Company (Maynard) offered to fit .25-caliber barrels to a customer’s existing frame. John Barlow’s Ideal Manufacturing (in business for eight years) had by November 1889, in stock, the new 25720 bullet mould. At first, the 77-grain version was the regulation bullet, but this had changed the following year to the 87-grain version of the same bullet. The “short pointed” 25719, to be cast 1:40, was an option the minority preferred. Massachusetts Arms also made moulds, as did U.M.C.

Instantly, the Stevens Arms and Tool Company offered its Tip Up rifle in both .25 Centerfire and Rimfire and were filling orders by February. They would rebore and rerifle their own rimfire rifles for the new .25 Rimfire. Harwood wrote that he sent a Ballard .22 to be so converted and was delighted with the result. The Stevens factory wrote that it was “running ‘til 9 p.m.” to keep up.

Meantime, the .25s were beginning to gain acceptance and some notice in the press. Initial range reports were generally very favorable with 4.5-inch groups at 200 yards from the centerfire round being a good average. Harwood’s results, for whatever reason, didn’t quite meet this standard. His preliminary tests showed that the factory 86-grain cartridges were poor performers and blamed it on the 15-inch twist of his Maynard rifle. The 66- and 77-grain Ideal bullets, cast 1:40, did much better work.

The black powder .25-20 became very popular as a small-game cartridge with New England’s woodchuck and squirrel hunters, but to the precision-minded rifle crank, it was primarily a target cartridge. In the early to mid-1890s, many shooters filed reports of 200-yard groups in the 3-inch neighborhood, at a time when a rifle that would keep all of its shots within an 8-inch bullseye to be a “jewel,” to use Harwood’s criteria and expression. Later, Harwood admitted to having some insider knowledge relating to the cartridge’s development. He had been a guest at the Maynard factory during the summer of 1889, where he was shown a test target from a prototype rifle. Seven successive shots landed in a 2-inch circle.

Although the .25-20 continued in popularity through the early 1890s, it wasn’t regarded warmly by a certain segment of the era’s riflemen, who objected to its bottlenecked configuration. This type of shell, it was believed, was difficult to reload and very prone to splitting at the body/neck juncture. Their consensus was that for a cartridge to be successful in the marketplace, it simply was to be straight walled. From here and there came occasional reports in the sporting journals of the slightly bottlenecked case of the .25-20 Single Shot parting upon firing. Most shooters saw this as simply their cross to bear, and that the .25-20 needed superseding for this reason was not the thought of the mainstream.

Carpenter maintained that he was able to calculate an internal volume of 20 grains of black powder. He concluded his missive with a question: “But what rifle company will be the first to chamber their .25 caliber arms for this shell?” On its face, the suggestion of a totally unknown individual with no stated qualifications and no specified credentials to recommend him, and armed only with a straight edge and sharp pencil, might have seemed preposterous to many and didn’t stand a snowball’s chance of serious consideration. To those open to the plan, he presented a good argument.

The scoffers, as they often are, were proven wrong. Curiously, Carpenter’s seemingly flimsy plan appealed to the Winchester Repeating Arms Company, and an exchange between he who conceptualized and the entity that could make it real was soon underway. In March 1894, an agitated and impatient Carpenter sent a letter to the Forest and Stream editorial offices, apprising them of headway to date and venting that certain manufacturers were dragging their feet and impeding progress in the promised release of rifles chambered for his proposed cartridge and the perfected ammunition. Carpenter hoped that a published reproduction would shame those alluded to and thereby speed matters along.

Several inquiries from interested parties had contacted Carpenter, anxious to be updated. John Barlow of Ideal in particular, anticipated supplying the riflemen with reloading tools and was needy of certain specific particulars in order to be ready with his goods. A body of other interested individuals was also looking for answers. It had been eight months since Winchester had indicated that rifles and cartridges would be “ready in a month.” Carpenter then visited the Winchester plant, where he was put off with the promise that they would be “ready in two weeks.” Five months later, the armchair designer was told that nothing yet had been done about it. Carpenter then cautioned his fellow Forest and Stream readers to be on guard against such “pernicious influences” and to beware in dealing with concerns prone to such “lapses in veracity.”

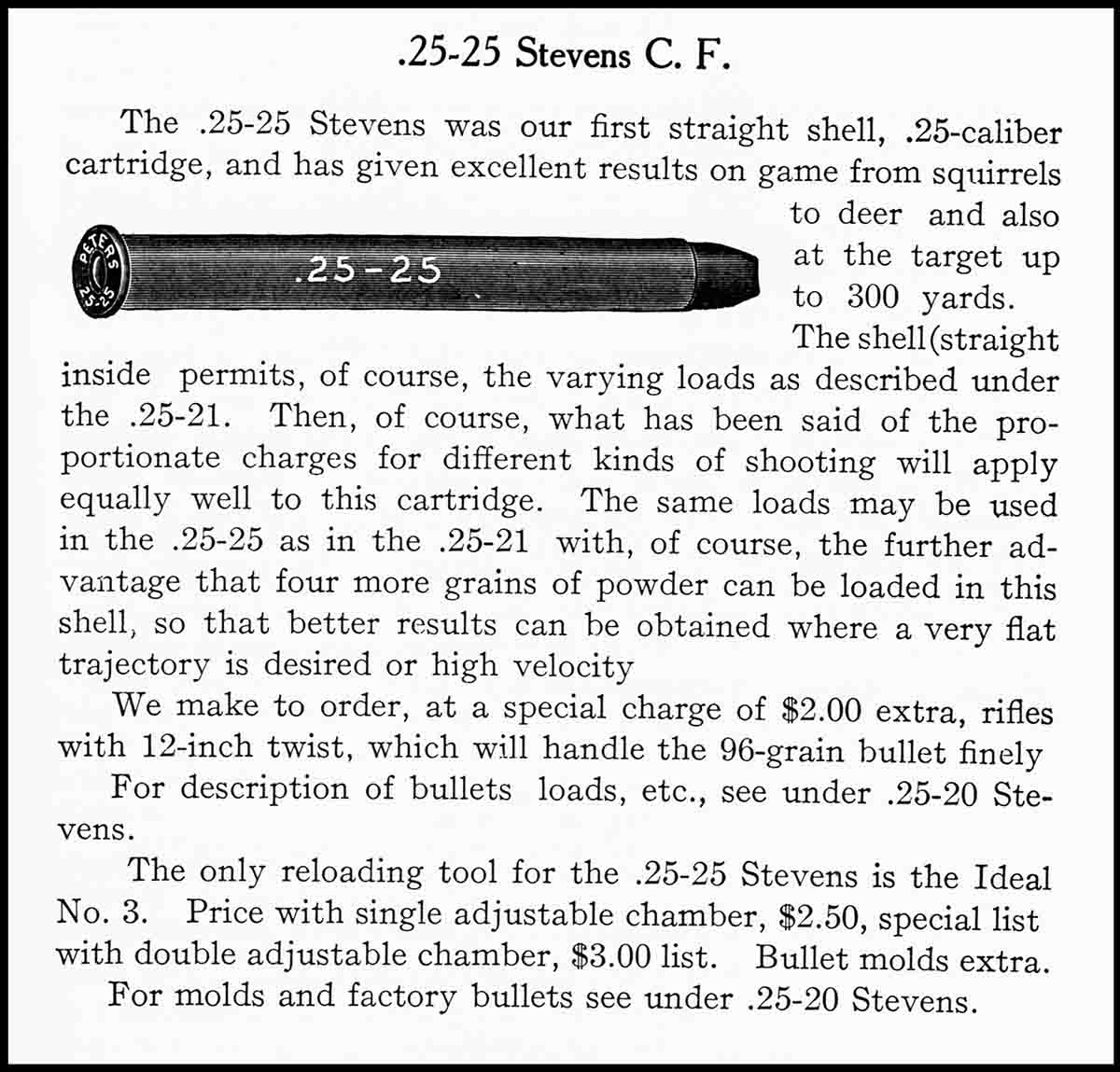

The up-to-date rifleman embraced the combination and found it was accurate. The expected binge of orders for the newest and latest came to pass. Published testimonials from first purchasers prolonged the initial flurry, as manufacturers had counted on. The announcement of a new cartridge these days draws the same predictable attention and public reaction. J.B. Fellows may have benefitted from a preproduction gun and almost instantly responded and enclosed a target which he claimed “…is the best ever done at Walnut Hill with any rifle of .25 caliber.” L.W. Pow of Salem, Ohio, wrote what wasn’t much in the way of testimonials but some prospective buyers could relate. Stevens used it nonetheless: “I have one of your late rifles, .25-25, which is a dandy to shoot.”

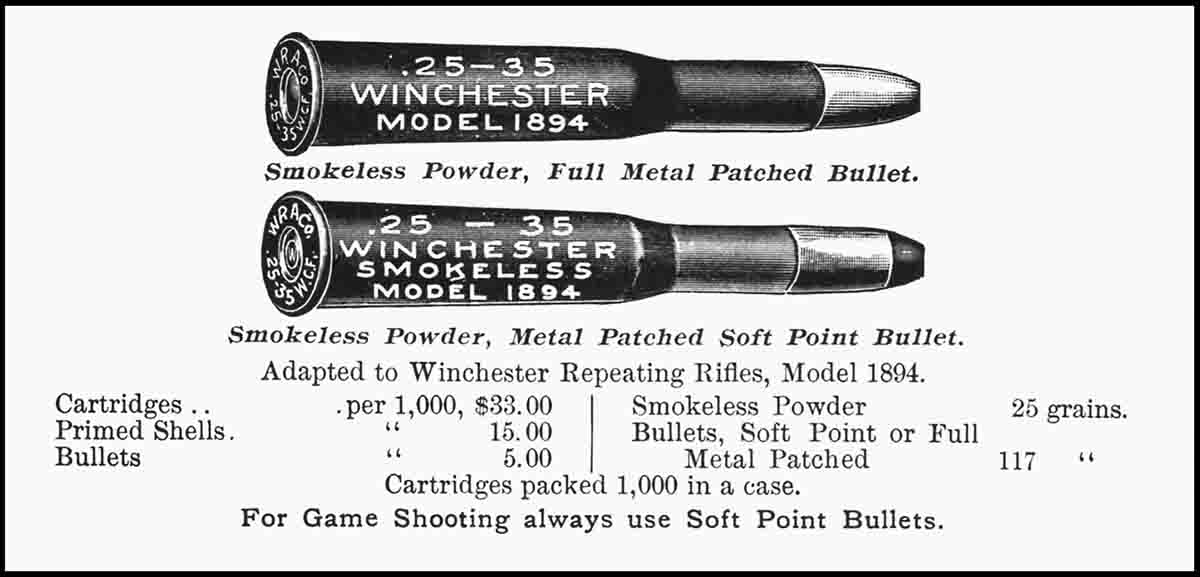

It behooved the arms industry to keep abreast and apace with the times during this new epoch in sporting ammunition. Winchester was aware, and it was for this reason that their .25-35 W.C.F and the Marlin .25-36 were both on the market by the fall of 1895.

John Barlow, communicating in the Ideal Handbook for 1895, updated the public on his company’s continuing role in supporting the .25-caliber enthusiast. Ideal could furnish reloading tools and bullet moulds for a variety of bullets, including the proven 25720 and two flavors of pointed bullets, the “long pointed” 25718 and the “short pointed” 25719. The Ideal Perfection Mould, newly patented in 1891, would cast the full spectrum of weights for any of these standard styles.

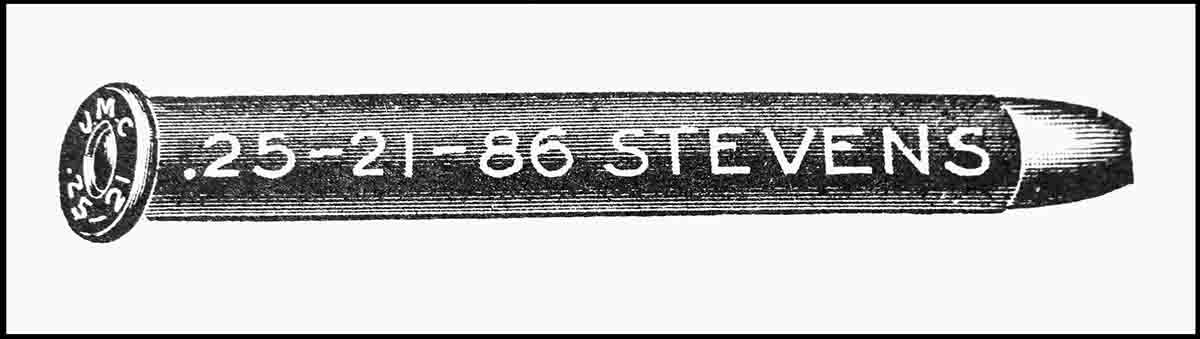

The May 8, 1897, edition of Forest and Stream carried the official unveiling of the latest and last in the series of fashionable .25s, known by the mouthful “.25-21-86 Stevens Straight.” Throughout the years, it has been maintained that Captain Carpenter was responsible for designing the .25-21 in addition to the .25-25. However, Stevens published announcement suggests otherwise. In print, Stevens directly stated that the new .25-21 is a “modification of the .25-25 cartridge.” They were less than forthcoming with a reason for the change. Phil Sharpe, who purported to know, tells us that the .25-25 was shortened to eliminate extraction troubles associated with the longer case. There was a measure of contemporary testimony that confirms this, and a few references to the use of a cleaning rod often used to start stubbornly stuck cases. The brand new case was, in essentials, shortened but .220 inch, which insignificantly reduced case volume, powder charges or velocity.

Stevens used the occasion to rehash the “straight versus bottleneck” issue, which it refused to let die with this shining example of the company’s salesmanship: “Any cartridge to become popular and retain its popularity must be straight, or nearly so, especially straight inside.” This less than convincing justification was a tough sell at a time when army ordnance had chosen a modern “bottle-shaped” cartridge of high pressure as its current service round. The Krag rifle and its necked ammunition was then experiencing a tremendous level of popularity, which amounted to much more than a fad. Much of the perception of the new .25-21 depended upon a shooter’s impression of its longer predecessor. Those already owning a .25-25 didn’t need what was essentially a shorter duplicate. Then, too, in the minds of many, the untried .25-21 was already painted with the same brush that had daubed the .25-25.

A better idea of what could be done by that era’s “gun crank” was put on paper by Ned Roberts, history’s most noted .25-caliber fan. He treated the .25 caliber vogue as another project to be successful at. At any point in time, he’s worth listening to.

His last .25-20 Single Shot was an A-5 scope-sighted Winchester Single Shot, 28-inch nickel steel barrel. As thoroughly as few would, he tested it with all manner of smokeless and semi-smokeless powder and breech-seated bullets. Though he had every reason to hope for better, 100-yard groups were no closer than 2.5 inches.

In 1906, Roberts received a Lyman sighted Remington No. 2 chambered .25-25 Stevens Straight. Like so many others using factory cartridges, he was plagued with black-powder fouling, requiring cleaning after every 10-shot group. Smokeless powder and more than a single bullet style combined to coax acceptable groups. He also had a Stevens 44½ .25-25 that was tested at the factory to print 10-shot, 1.5-inch groups. In Ned’s hands, the gun didn’t stack up to the machine rest accuracy, but it wasn’t for the lack of trying or his knack for wresting the most from a rifle.

Roberts admits to having at least one .25-21 in the pile of rifles he had owned and shot. Details on his .25-21 are hidden somewhere in his writing over the years.

When some trends seem to overlap, the least vital takes the back seat. Growing interest in the 1890s .30 calibers, the growing interest in military marksmanship, the dominating goings-on during the peak years of the Schuetzen era, and the advent of the smokeless-powder era overshadowed the need to invest needless ink and magazine space to popularizing another outmoded .25 caliber. The once trendy .25s were experiencing the last vestiges of vitality. Much of the best material written concerning the two long Stevens cartridges was put down in feature articles when it was not exactly timely, but when their capabilities could be examined in a more thorough and modern light. The “rest of the story” should be considered a renewed aspect of the craze and not as a postscript.

After nine shooting seasons, Loetscher demonstrated that he’d advanced considerably as an experimenting rifleman. He filed an update of his previous results in the May issue of Outdoor Life. During the interim, he’d spent a lot of range time with the bulk smokeless powders Schuetzen and DuPont No. 1. He had yet to buy another bullet mould. His one bullet was the 86-grain Ideal 25720, cast 1:60 with its two forward bands ahead of the case mouth. For using just one bullet, he got good overall accuracy. One hundred-yard groups averaged 1.5 inches using black powder, while smokeless loads printed five-shot groups an eighth-inch larger. In closing, he admitted that he’d tried “combinations” (priming charge of black powder) but didn’t see an advantage at the target.

In his essay, “Black Powder in the .25-21,” (found in Outers Book October 1916, and basically a rehash of his earlier findings,) Loetscher disclosed his experience with the shell dating back to 1905, when Schuetzen Smokeless was unknown and the cost of DuPont No. 1 Smokeless was three to four times that of good black powder. For this reason, his use of early smokeless was very limited. He also provided his observation that in his part of the country “the .25-21 is not in very general use, and consequently cartridges often stand on the store shelf for years, deteriorating and when at last sold to the user their accuracy is sadly affected.”

This provides an insight into the dwindling popularity of the caliber at the time. Here too, Loetscher described his technique to settle FG black in the shell without compressing it. He used a section of close-fitting steel rod to lightly tamp the column of powder, striking it lightly a prescribed number of times. Alfred Loetscher was no slouch as a rifleman or experimenter. Hervey Lovell said of him in 1921: “I have been given two machine rest targets by Alfred Loetscher showing just what the careful man and one gun can do in loading.” Compared to Loetscher’s .25-21 groups, he said, “most of my rest targets show only what I can expect shooting offhand.”

Six years before C.S. Landis sat down to write his first of six books, The Use of Rifles for Game and Target, he weighed in on the subject of .25-21 shooting on the pages of Outers Book for April 1916. “Small Bore Loads Fit to Shoot” was the era’s best-done and most significant treatment on the subject; it was so informative that, years later, Ned Roberts cited it. Landis neglected to mention the particulars of his rifle, but did specify its 9-pound weight without the telescope. Doing all of his shooting at 50 yards eliminated much of the wind’s influence. Most of his groups didn’t stray from the 1-inch bull. Landis observed the same black-powder fouling that was universally experienced. It was annoying and destroyed accuracy, and needed to be often removed. After looking at too many 2.5-inch groups, he switched to semi-smokeless, with and without a black-powder priming charge. Straight Schuetzen smokeless performed magnificently.

Tracing the nearly parallel lines on a sheet of paper to illustrate a rifle cartridge’s design was not Captain Carpenter’s chief contribution to mankind. Born in 1844, William Lewis Carpenter was a military man, a naturalist at some advanced level, and had a training and background as a geologist.

After spending the Civil War in the Union Navy, he accepted an officer’s commission with the U.S. Army in 1867. As part of the Seventh Infantry, he was a member of the 1874 Army expedition to explore the Black Hills, map the region, and document the minerals found. Gold, of course, was among them. The announcement of harvestable gold lead to an inevitable rush and its ripple effect of an influx of prospectors, troubles with the Sioux, and the predictable outcome of the Sioux War of 1876. Later promoted to captain with the Ninth Infantry, he became part of the same type of exploration of the Big Horn Mountains.

Following the Wounded Knee debacle, the Ninth was no longer needed to police the reservation and the unit was transferred to garrison duty at Madison Barrack, New York, in 1892. After seeing his slim .25-caliber cartridge case see the light of day and effecting the swing to .25 caliber during the “Gay ‘90s,” Captain Carpenter died at the Madison Barracks in July of 1898.