Winchester’s 1873 Saddle Ring Carbine

feature By: Mike Nesbitt | June, 22

This version of Winchester’s Model 1873 is made by Miroku in Japan. I don’t think any of the Winchesters (or the Brownings) are made in the U.S. anymore. While this new rifle is certainly a Model 1873, with the toggle-link action and the brass cartridge elevator, we can’t say it doesn’t include some changes. Sometimes, I like my “authentic” copies to be absolutely authentic, but often we must recognize some of the newer ideas as “better ways of doing it.”

As we should expect, the Winchester carbines are more authentic than the other ’73 copies, mainly because this Model ’73 carbine has a 20-inch long barrel. In addition to that, the front sight on this carbine is the way it should be with a brass sight blade pinned between the two supporting blocks that are soldered to the top of the barrel. The very early ‘73s did use a front sight formed on the top of the forward barrel band, as did the Model ’66 carbines, but that was changed to the pinned blade rather early. Besides, that forward barrel band can rotate slightly, which affects windage. The proper carbine barrel length and front sight please me, most certainly.

The tang is drilled and tapped to accept a tang sight, such as Lyman’s #2 or the Montana Vintage Arms Combination tang sight that are both currently available. However, on the Winchester Model ’73, the rifle’s main tang screw is not replaced with the rear screw to attach the sight. Instead, two of the front screws must be used because the sight mounts just forward of the tang screw. This means shooters who want to use the tang sight must buy an extra front screw in order to mount the sight to the rifle. Looking at old original Winchester ’73s, that’s the way the sights were added, with two small screws instead of replacing the rifle’s tang screw..

This is a good time to mention the “newer idea” that was hinted about earlier. On the top of the receiver at the back of the dustcover guide, there is a new screw that holds a vertical pin. That pin engages what appears to be a firing pin block inside the narrow round bolt that extends out the back of the receiver which we recognize as the part of the bolt that cocks the hammer when the action is opened. This, I believe, prevents the firing pin from being able to fire a cartridge unless the action is completely closed. Not a bad new idea at all.

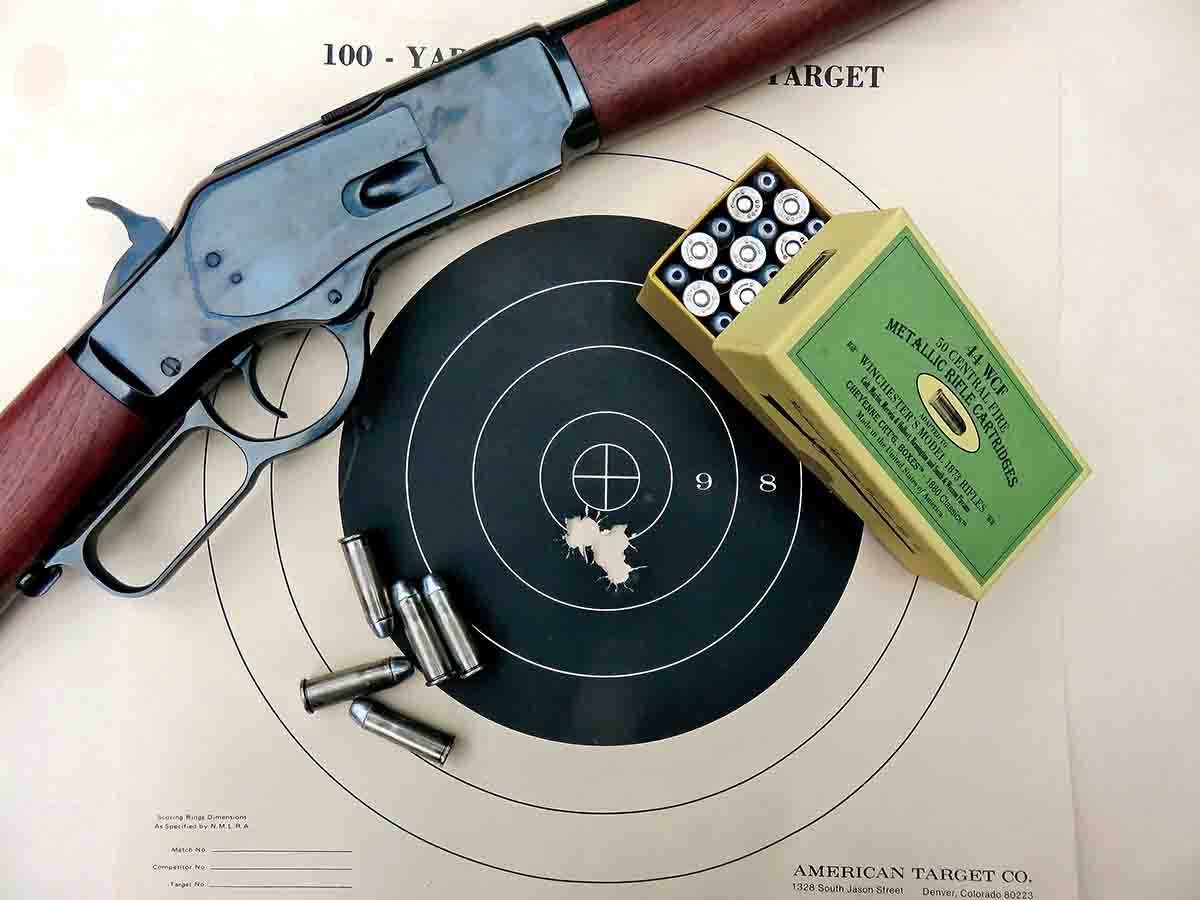

For our shooting test, only black-powder handloads were used. The breakdown of those loads includes the nickel-plated cases from Starline. I prefer the nickel-plated cases with black-powder loads because they are easier to keep clean. Bullets were cast with my old mould from Lyman, 427098 using a 25:1 lead-tin alloy as supplied by Buffalo Arms Company. Those bullets weigh 210 grains, or 205 grains with the hollowpoint. As mentioned in the previous paragraph, those bullets were sized to .429-inch diameter and lubed with BPC from C. Sharps Arms. All loads were primed with CCI’s 300 standard Large Pistol primers.

Powder charges need a bit more of a description. Most of the cartridges were loaded with 35 grains of Olde Eynsford 2Fg powder, both with hollowpoint and solid nose bullets. But 10 of the cartridges were loaded with 35 grains of Olde Eynsford 3Fg powder just to see if there was any real difference in performance. The loads with the 3Fg powder had their primers blackened for easy identification. For the 3Fg loads, only the 205-grain hollowpoint bullets were used.

Results from the chronographing gave us a little bit of a surprise. The loads with the 35 grains 3Fg Olde Eynsford were fired first and they averaged 1,282 feet per second (fps) out of the carbine’s 20-inch barrel. Our small sample of velocities had an extreme spread of only 20 fps. Then some loads with the 2Fg grade of Olde Eynsford were tried and they had an average velocity higher than the loads with the 3Fg. Not much higher, only 8 fps for the averages but even so, it was higher, with an average of 1,290 fps. The highest velocity recorded was fired with the 2Fg powder, as well as the lowest velocity. The few shots we fired with the 2Fg powder had an extreme spread of 33 fps from the slowest to the fastest speed recorded.

The .44-40 is regarded as a short-range cartridge and with that in mind, I found no shame in posting a target at 25 yards and shooting five shots for a group while using the standard carbine rear sight that the gun comes equipped with. Those five shots, by the way, were taken with ammunition loaded with the 35 grains of 3Fg powder. They grouped extremely well, all going through one jagged hole just below the X-ring, scoring in the 10 and 9 rings. If this .44-40 can group like that at 25 yards, it will group almost that well at 50 yards or even longer distances. After getting that group, we shot some more, but just for the fun of it. That’s when we did more offhand shooting at some very small targets of opportunity, such as broken chips of clay pigeons.

In my opinion, Winchester made a real good move by bringing back the Model 1873, carrying the Winchester name. They do tend to market toward the Cowboy Action shooters more than buffalo runners like us, so the .357 and .45 Colt are more commonly encountered chamberings. Several versions are made including rifles, short rifles, carbines and trapper carbines. These rifles are sold wherever Winchesters are in the sales rack, but if I was looking for one, which I am, the first place I’d look at would be Buffalo Arms Company at buffaloarms.com.