The Wyoming Schuetzen Union’s “Center Shot”

Gleanings from Bannerman’s 1907 Catalogue

column By: Jim Foral | June, 23

The state of these things for our ancestral gun crank at the dawning of the last century was rather grim in comparison. That person absorbed whatever slanted information he could glean from the black and white type in gun catalogs or what questionable wisdom he picked up at his gun club. What little mutual exchange that there happened to be was in the form of letters published by the very few sporting papers then in circulation. The city dweller often bought his guns and gear at a sporting goods store while the rural shooter shopped by mail order or sight unseen used guns via the classified ads in the major outdoor magazines. They may not have had the variety of utensils, equipment, or option we take for granted, but they had one outlet that we would envy: they had Bannerman’s.

Bannerman considered the waste involved in that current practice and reasoned that there would be more value in the guns as relics and heirlooms. He curtailed his part in the destruction and set out to market the items as artifacts and built a successful business in doing so. In New York, he established a seven-story, 42,000 square foot office/salesroom displaying a thousand different pistols and a like number of swords. The heaps of long guns were likewise strong sellers. He took a gamble, bidding more than his competitors on cannons and heavy ordnance and found a ready international market.

Just after the turn of the century, a European shipping firm sold an obsolete steamer to an unnamed South American government and commissioned Bannerman to convert it into a warship, supplying and installing the necessary cannons and other armament. His crews armed, outfitted, and delivered the completed vessel within seven days, and the county had a formidable, modern, defensive one-boat navy on the budget of a poor nation.

The catalogues first few introductory pages were taken up with selected testimonials from all points, after which formalities such as Bannerman’s conditions for buying and instructions for ordering and payment and conditions governing the sale of goods.

A veritable museum-quality offering of assorted wheel locks and matchlock weapons of bygone ages was found on the next page. Following that was two full pages of crossbows of many sorts, and the inclusion of bows and arrows collected from “savage tribes” in the Congo and other parts of Africa.

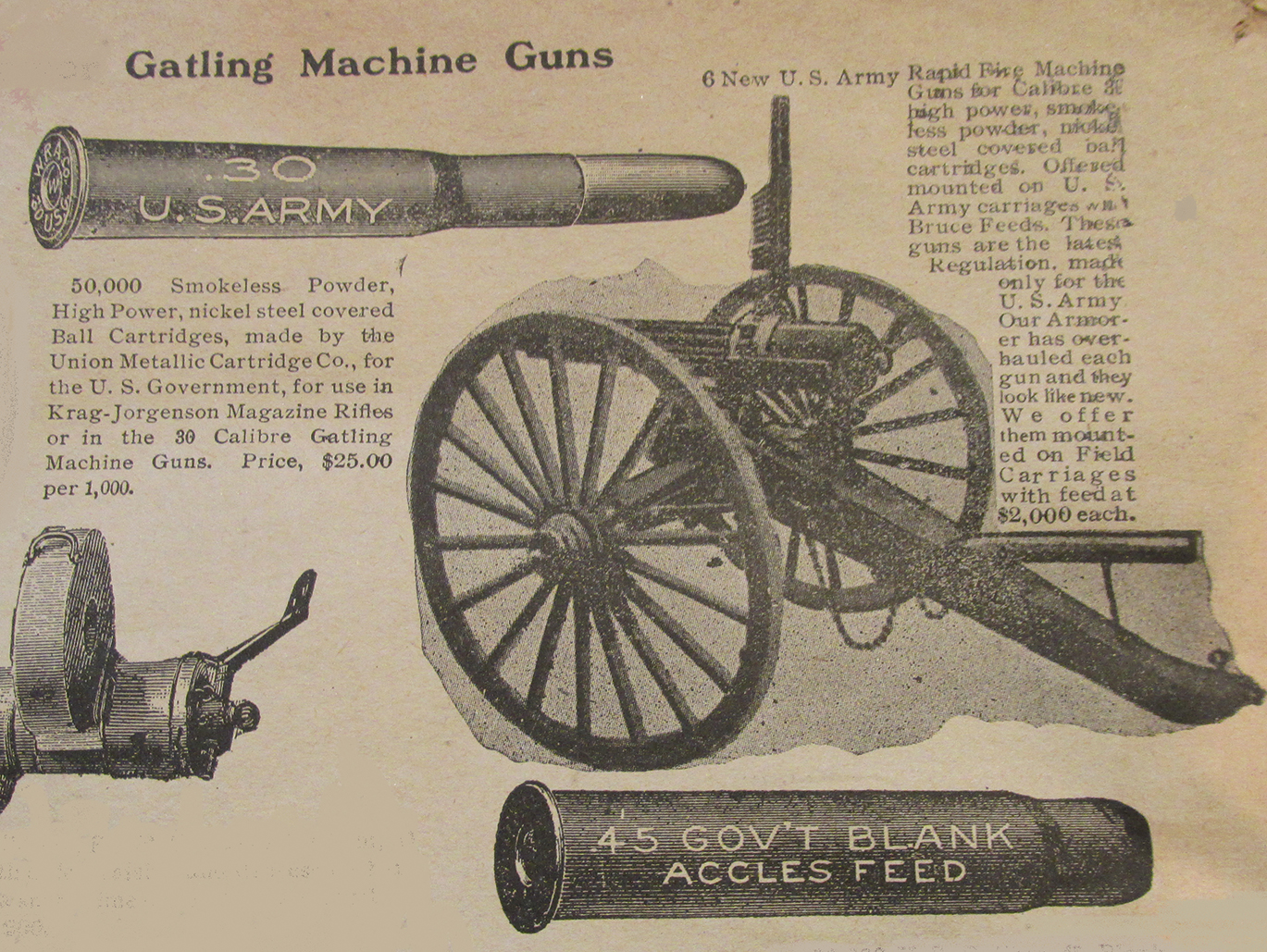

Bannerman’s lineup suddenly got meatier with the presentation of his Gatling guns on page 11. Limbers and field carriages with fixed ammunition boxes rounded out the Gatling package. These were the same Gatlings that kept the Spanish heads down to allow the Rough Riders to advance on their assault of the San Juan Heights on July 1, 1898. At two thousand 1907 dollars, they were not cheap. Buyers were going to need ammunition. Anyone flush enough to spring for a Gatling wouldn’t have balked at paying $25 per 1,000 for the 30-40 U.M.C. cartridges necessary to rattle off 400 to 900 rounds per minute. Bannerman had 50,000 of these cartridges in stock. Left over from somewhere was a short-barreled version Gatling for use from camel’s back complete with saddle and gun mount.

Grouped with these guns was a number of lavish European single-shot target rifles and a massive bow-mounted whaling harpoon gun, which Bannerman opined, in apparent seriousness, would double as “a good ducking gun.” Those like-minded may have developed an interest in either of the two English break-open hammer guns that fired seven 32 rimfire shots with a single trigger pull. Intended for shooting geese at long range, this gun was just the rimfire ticket for flock shooting or polishing off distant cripples.

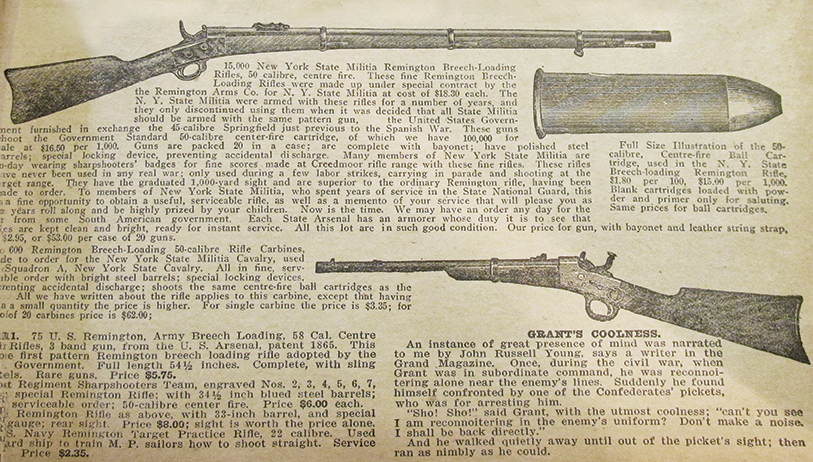

More to our general liking and seemingly out of place among the many and various mundane “breech loading shotguns and sporting rifles” shown on pages 26-30, was a 10-pound Remington Creedmoor rifle of .45 caliber for $14. A like gun in .44 caliber, sighted for its intended target use, was listed as “new but shopworn” for $9.50. There was a magnificent Officer’s Model trapdoor Springfield with detachable pistol grip, engraved lock plates and sighted like a match rifle for $16. Two others, not as nice, were listed at a dollar less. A Sharps .40 caliber Creedmoor rifle, sighted as you would expect for 1,000-yard target work. It originally cost $200, and was on sale at 1907 used gun prices for $18.

Page 25 arranged a sizeable assortment of guns that were said to have been confiscated from Indians. Included was a weapon reportedly captured from “Sitting Bull Indians after the fight.” In 1907, Bannerman’s disclosure may not have added much value apart from the curiosity element. Nowadays, even his dated assertion would magnify the asking price considerably.

Bannerman’s bidding brought him the six historic Trapdoors recovered from the battleship USS Maine as it lay in the Havana harbor in 1899. Four of these would be sold if he could get his asking price of $40 each. The remaining two were destined to remain in his museum. Included in the haul were the 54 Winchester 6mm Lee Navy repeaters also taken from the USS Maine. Their serial numbers, and those of the recovered Trapdoors, were listed on page 35, along with unassailable documentation from the U.S. Navy Department.

A sizeable cluster of basically uninteresting prototypical and inventor’s model guns, mostly European, filled an entire page with fine print, and a listing of obsolete foreign military rifles also took up its share of space.

With the intention to export them to South America, Bannerman bought up 18,200 Spanish Mauser 7mm rifles. Complementing this windfall was the winning of seven million rounds of the enemy’s ammunition. The U.S. gun market was saturated with this stuff for years thereafter.

Bannerman had a thousand Spencer .50-caliber repeating rifles. They were described as “new in factory cases.” These new guns could be bought for $3.50. “A few hundred” used seven-shot Spencers were on sale for $2.95. There was plenty of ammunition – 700,000 – copper cased cartridges priced at $13.75 per 1,000.

What we might consider an odd thing to catalog with an already unusual line was a chunk of real estate with a gun factory upon it. Bannerman owned the old Spencer Repeating Arms plant in Brooklyn and devoted the whole of page 49 to his effort to sell it. Spencer had closed the business in 1869, and Bannerman was able to acquire the building, together with its machinery, tooling, and fixtures. The package was described as “complete and ready to work.” Its owner seemed eager to close a deal, and that “a quick buyer can purchase this plant at a bargain.”

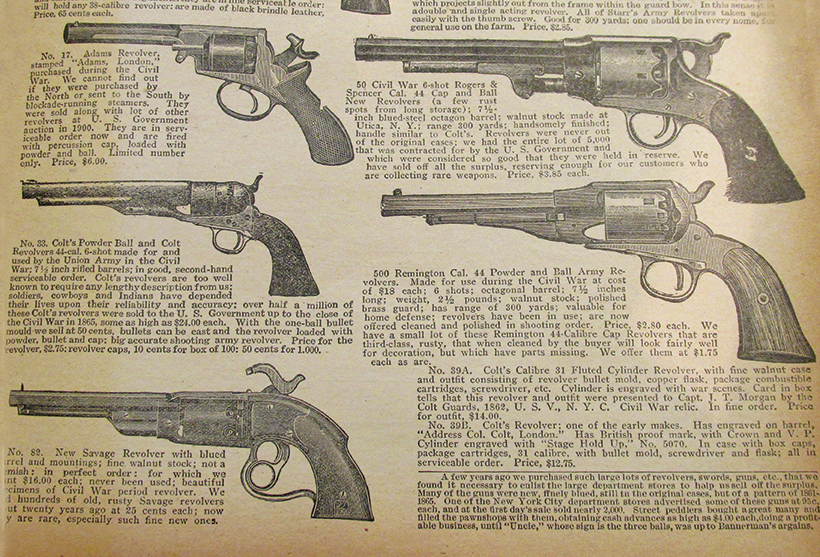

Bannerman presented his expected share of pistols to his diverse mix of stuff for sale. Ignition types ran the gamut from matchlock and flintlock to surplus cartridge revolvers and the self-loading Luger. He had an unusually remarkable assortment of cased dueling pistols. Featured prominently among them was a pair of duelers that had been presented to General George Washington. Their ownership had filtered down through a short series of prominent figures until they reached Francis Bannerman who won them in a sealed bid auction in March of 1903. By 1907, he offered them for sale and stood firm that “It would take an offer of $10,000 to induce us to part with these historic relics.”

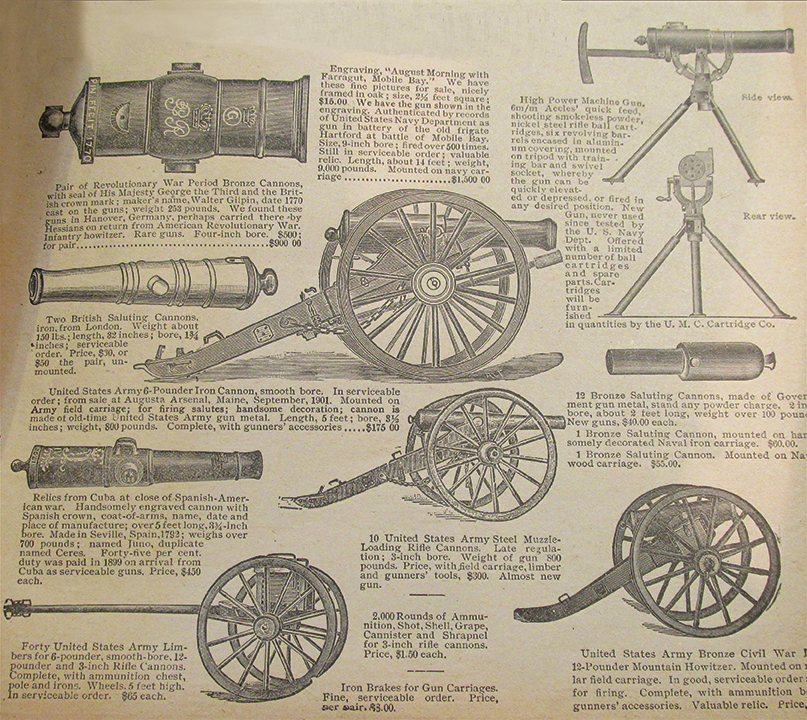

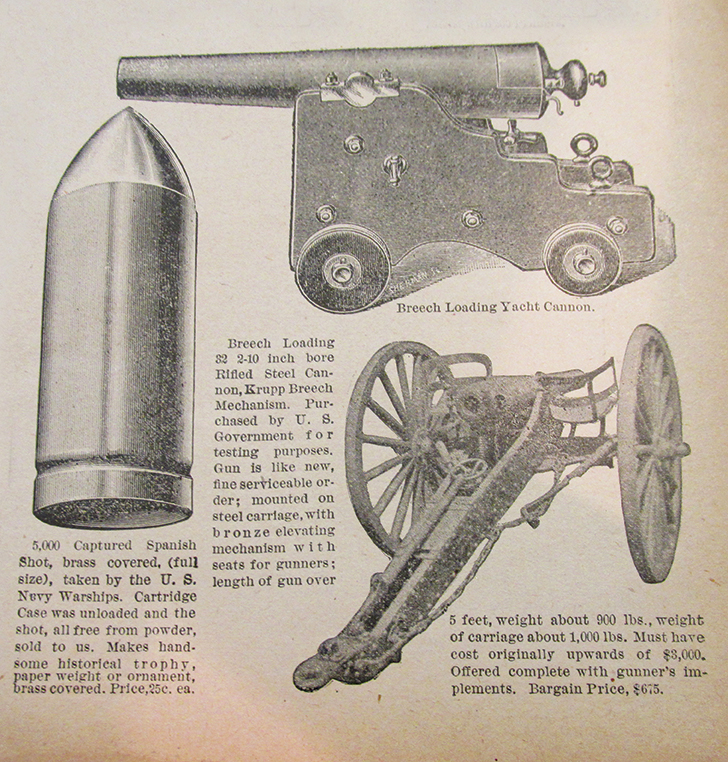

The inclusion of cannons in his catalogue showcased the scope of Bannerman’s enterprise. He listed most conceivable models of artillery variations through the progression of their development from the 8-inch Civil War mortar cannon through the dynamite guns used in Cuba and the modern 3-inch, semiautomatic rifle cannons of the current day. The largest was a U.S. Naval cannon weighing 10,000 pounds. One could obtain from Bannerman’s, seemingly without restriction, a Hotchkiss Mountain gun with a 1.65-inch bore and 4,000-yard range, mounted on a field carriage and ready to be towed to the nearest front. If a person needed more than one, this was easily arranged. The same could be said of the Hotchkiss 3-inch Mountain Cannon and the Hotchkiss five-barrel revolving machine gun. He had in stock several serious-looking bronze cannons that still meant business. Leftover ordnance, both live and inert, from both sides of the combat in Cuba was offered. Spanish artillery shells from the 1-pounder rapid-fire gun to the 1,300-pound, steel-piercing shell with a range of 13 miles could be had for a price.

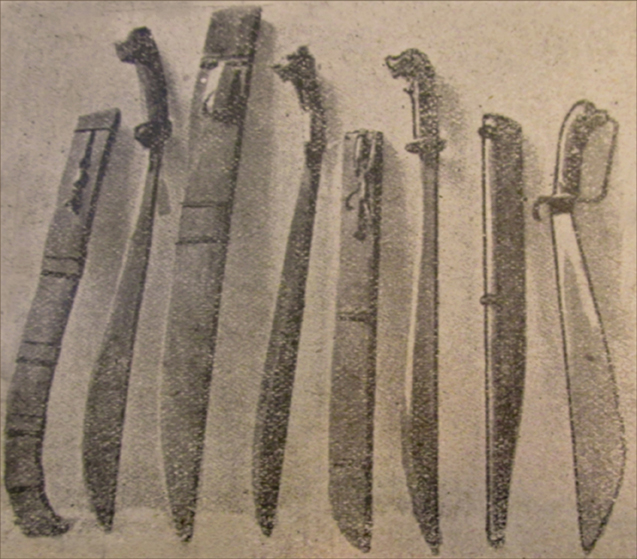

Captured in the recent Philippine fracas was a great assortment of edged weapons such as barongs, bolos and kris. No Filipino would be without his bolo until a U.S. Army trooper took it away from him at bayonet point. For sale, too, was a Filipino Talilong, or executioner’s axe that was used to behead two insurgent natives the morning its wielder was relieved of it; the story was vouched for by a U.S. Army Scout. The gruesome artifact could have been delivered to the door of any Bannerman catalog browser with the interest and willingness to part with $15.

In the final analysis, I consider my fanciful time traveling back to 1907, to have been a welcomed, whimsical adventure and a worthwhile day’s browsing.

.jpg)