The 44-90 Sharps Bottleneck, a cartridge that set the pace for other long-range cartridges.

The old 44-90 Sharps bottleneck cartridge is certainly a favorite of mine. The rifle I have for it, a 13½ pound 1874 Hartford by C. Sharps Arms, has given me better scores and more wins in our short-range matches put on by the Black River Buffalo Runners (with targets at 100 and 200 yards) than any other rifle. It has also been the best for me at long-range and it is one of only two rifles I have with long-range sights; the other gun is a Rolling Block in 44-77. Also, that 44-90 rifle gave me many hits on the buffalo silhouette out at 1,200 yards, down on the range near Bend, Oregon. In addition to that, my 44-90 was my choice for use at the big Quigley Match for several years and I used it more than any other rifle or caliber. The only reason I quit using it was simply because of increasing interest in other guns or cartridges.

One short-range victory stands out in my memory, when I shot a 94-2X at 100 yards plus another 94-X at 200 yards, giving me the high score of 188-3X for the match. (My prize was a framed print of a Fred Fellows painting.) That was a few years ago back in 2017, and I haven’t been able to do that well again. The load I used had 90 grains of my favored Olde Eynsford 1½Fg powder beneath a 470-grain bullet from Lyman’s discontinued mould #446187 sized to .446 inch, all wrapped up in a Jamison case.

Mike’s 44-90 Sharps, with a heavy 32-inch barrel.

When I first got interested in the 44-90 Sharps, I was fascinated at how this cartridge shot its way to fame in the Creedmoor matches, including the International Championships. Actually, that was not the case, pun somewhat intended. The 44-90 Sharps must share those victories with other 44-90s. One of the champions in those early long-range matches, notably in the Rolling Blocks, was a 44-90 loading with heavy paper-patched bullets loaded in the 2¼-inch cases of the 44-77 and not the 25⁄8-inch cases of the buffalo hunters’ 44-90 Sharps. Another was the 44-90 Remington, which used a bottleneck case measuring 27⁄16 inch in length. This doesn’t take anything away from the 44-90 Sharps, it only increases our knowledge in the background of long-range cartridges.

Mike’s target at 100 yards holds a score of 94-2X.

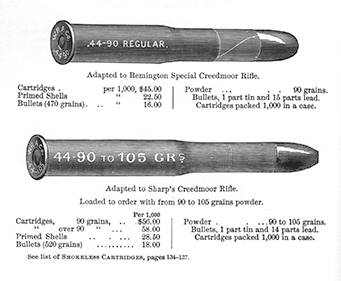

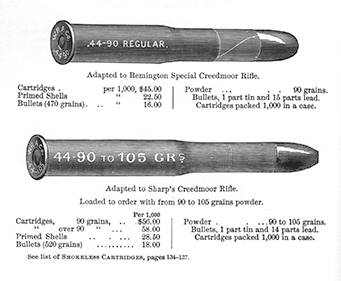

The 44-90 loading in the 2¼-inch cases was often referred to as the “44-90 Regular.” Additionally, Remington introduced straight-cased versions of the 44-90 and 44-100 in 1880, for their Hepburn rifles used for long-range target shooting. The “family” of large-cased 44s was actually a big one.

The 44-90 Sharps, according to both Sellers and Marcot, was introduced in June, 1873, and it was well accepted by the buffalo hunters. The 40-90 Sharps, which also has a 25⁄8-inch long case, was introduced maybe a month later. The 40-90 remained on the “active list” after the Sharps company re-formed and relocated to Bridgeport in 1876, but the 44-90 was replaced as a standard caliber for the Sharps rifles by the new .45 with the 27⁄8-inch case, which is what we call the 45-110 today. That simply means the 44-90 was in the spotlight for a rather short time although it was still available on special order during the Sharps Bridgeport era.

And while the 44-90 was accepted by the buffalo hunters as a cartridge that could reach out and get ‘em, it was not a popular sporting cartridge generally. Roy Marcot estimates that only 320 Sporting Rifles in 44-90 chambering were made between 1873 and 1878; his estimates are based on records from the Sharps factories.

From the 1899 Winchester catalog.

This individual cartridge that I have for the 44-90 Sharps is certainly an old one. It has the large Berdan primer and there is no headstamp on the cartridge. In general terms, that dates it into the 1870s, and this cartridge could be a full 150 years old. My guess is that it was made by Union Metallic Cartridge Company.

While I can’t vouch for this cartridge’s first 110 years, I can speak fairly well about its last 40 years. This cartridge was given to me by Dale Nelson about 40 years ago. He knew I was interested in Sharps rifles and I often hunted on his ranch near Roseburg, Oregon. When he gave it to me, he admitted that he didn’t know what it was because of its lack of a headstamp. Also, someone had torn the exposed patch paper from the bullet.

Let me explain the various coloring that the bullet displays. The more silver color, toward the base of the bullet, is where the original paper patch remained, that portion which was inside the neck of the case. Forward of that there is a darker coloring to the lead, which shows the length of the patch that covered the bullet after I re-patched it; forward of that is the exposed part of the bullet. I re-patched the old bullet and carefully re-seated it in the case to simply keep the old Sharps round as a collector’s item.

The original 44-90 Sharps Bottleneck cartridge.

Notice the head of the cartridge, no headstamp and the large Berdan primer.

As a piece in my collection, it was often compared to the new cartridges I’d prepare to shoot in my 44-90, sometimes photographed with the newer rounds for comparison. Any thoughts about taking it apart to see what was on the inside didn’t occur to me until after dissecting the 44-77 cartridge and firing the one shot with a new cartridge which was loaded with the old powder. The same format, more or less, was followed while investigating the insides of this old 44-90 cartridge.

First of all, this cartridge had an overall length of 3½ inches, which had to be noted. That had to be noted for proper re-assembly of the loaded round. Then the bullet was pulled by inertia so the bullet would not be damaged in any way. That was done with relative ease and the “insides” of the cartridge could then be looked at.

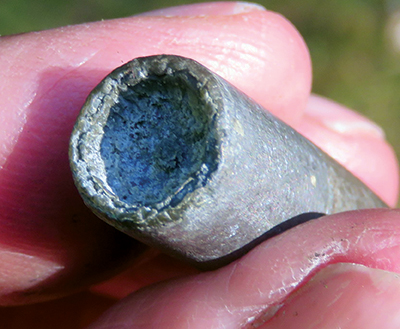

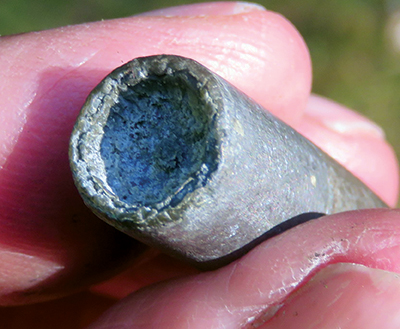

The bullet was actually a surprise. I expected this to be a sporting round, which generally had a 450-grain bullet. However, this bullet was much heavier, a 520-grain slug. In the old days, the 44-90s were available with either 500 or 520-grain bullets in addition to the 450 grainers and those were considered, perhaps by authors of more recent years, to be long-range target loads. It’s actually difficult to classify such things because if a hunter wanted the heavier bullets, he would have certainly been able to get them. This bullet was too heavy to weigh on my balance scale, which is maxed out at 505 grains. Measuring with a ruler, the bullet looked to be 17⁄16 inches long. The old 520-grain bullets were listed as being 113⁄32 inch in length, just about the same thing. This bullet seems to measure .441 inch near the base with a micrometer and it also measures .441 inch near the front of the bullet, which indicates that it is not tapered. It is a swaged bullet with a rather deep cup in the base.

The unpatched 520-grain bullet shows different coloring from exposure.

Beneath the bullet was a lube wad of about 1⁄8 inch in thickness. There was no card wad between the lube and the base of the bullet. Unlike the wad in the 44-77 case that I “dissected” this lube wad did not come out easily. It had to be chipped out so it came out in small fragments. If there was any card wad beneath the lube disc, I never found it. The wad, being perhaps just paper, was apparently destroyed while digging out the lube. I must assume that the lube was beeswax or some mixture with beeswax.

A deep cup is in the base of the bullet.

The patch paper was about .003-inch thick. Of course, that is the paper that I re-patched this bullet with about 40 years ago. I believe that was paper I bought in small tablets from C. Sharps Arms, which I used at the time to patch bullets for my 45-70 rifle. I wish I could remember more specifics about that paper but my memory fails me on that count. It does seem to be very similar to the nine-pound paper presently sold by Buffalo Arms Company, and that’s what I’ll use to re-patch this bullet.

Like the lube wad, the powder also had to be dug out of the case but not as difficult as the hardened lube. The powder had been compressed so it needed to be loosened just a little before it would pour out, into my scale’s pan. This powder, looking much like Old Eynsford 1½Fg, although a wee bit finer, weighed 88.3 grains. Some of the powder granules did adhere to the inside of the cartridge case and I tried to dislodge those with a small screwdriver. Also, the case has a balloon head and some powder remained in the “groove” between the sides of the case and the “bulge” for the primer. In addition to that, a few granules of powder came out with the lube disc and became lost in the handling. Given those variables, I’m going to assume that the powder charge was originally 90 grains.

Case and components; the lube had to be chipped out and the patch torn off.

Load listings shown for the old 44-90 seem to indicate that the 520-grain bullets were loaded over 105 grains of powder but that certainly was not always how it was done. Ammunition makers in those days would gladly load the ammo as ordered, generally in quantities of 1,000 rounds. As noted in the Winchester catalog, the 44-90 Sharps was shown as “loaded to order with from 90 to 105 grains of powder.” The bullet for those Winchester loads also weighed 520 grains.

The reassembled 44-90 cartridge looks like it’s ready for work

With all of those things looked at, it was time to re-wrap the bullet and re-assemble the cartridge. The original powder is being saved to be tried on a later day, and a 90-grain charge of Olde Eynsford 1½Fg is being put in its place. Actually, I thought about re-seating the bullet without putting powder in the case because it most likely will never be fired. Even so, it simply wouldn’t be a complete cartridge without powder. My re-assembled 44-90 cartridge needs to be complete, close to what it was originally, even if it is just for display.

The old 44-90 Sharps had its share of target and hunting history and is one of my favorite cartridges from that period. I’ll be using it, to be sure, for much more future shooting.