Ballard's No. 61/2 Rigby Rifle

feature By: Tom Oppel | May, 19

“A thing of beauty is a joy forever.” This is a well-known quote from Keats’ epic poem “Endymion” which continues, “Its loveliness increases; it will never pass into nothingness.” All of Keats’ lovely descriptive words, in my estimation, definitely describe the Marlin Ballard No. 6½ Rigby rifle; an example of which is the subject of this article. Photos will prove the appropriateness of using the Keats quote. If you are familiar with any of my prior articles on Ballard rifles in The BPC News, you know how I feel about them. To me, there were no commercially produced single shots of the late nineteenth-century era that even come close to any model of Ballard regarding aesthetics. I simply love the feel of a Ballard rifle when I pick one up; there is just something about it that evokes this reaction. Over the years, I have searched for a reason and consistently come up empty – many emotions lack logic. I try to control it but cannot – I’m hooked on Ballards and wish I had more of them.

To me the 6½ Rigby is the epitome of the Ballard line of rifles produced by Marlin from 1875 to 1891. In the visual category, the No. 6½ Rigby model has to be the most aesthetically pleasing and satisfying to the eye. The 6½ Rigby was produced from 1883 through 1891, according to George Layman’s Ballard book. From its engraved muzzle ring to its finely sculpted Swiss-style buttplate it just oozes beauty. I am not the only one who feels this way about the 6½ Rigby, as the author of the definitive book on Ballards, John Dutcher, apparently agrees, as the dust jacket of his indispensable book has two of them on it! The originator of this rifle in Marlin’s lineup (possibly John Marlin himself) certainly deserves a hearty pat on the back and a “thank you” from us for this creation.

For everyone’s information, there were essentially two Marlin companies that produced firearms from around 1875 through 1891. Brown Manufacturing’s failure in 1873 prompted New York retailer Charles Daly of the Shoverling and Daly sporting goods firm to buy the rights for the Ballard rifle. He then made an agreement with John Marlin to continue manufacturing the Ballard rifle, starting in 1875. Initially, the new rifles were stamped “J.M.Marlin.” In 1881, the company name changed to “Marlin Firearms,” which remained until Ballard rifles were no longer manufactured in 1891 and continues in some form to the present day. This knowledge is relevant as it impinges, in some cases, on the model variations throughout their manufacture. These two company names are reflected on the stamping on the upper left side of the receiver bridge. There is no model designation on any Marlin Ballard rifles that I know of, rather they are identified by certain characteristics found uniquely in each rifle. In some cases, this makes for interesting speculation as to a particular rifle’s actual model. An example of this is currently on the Internet where a seller is advertising for sale what he calls a Ballard “Pacific” when in actuality it is a “Montana” model, which is considerably rarer than the Pacific. They both have basically the same visual characteristics, but this rifle has more specific features making it a Montana. Even somewhat more confusing is that many Marlin Ballards lacked any cartridge chambering designation anywhere on the firearm; this is especially true on earlier models. When it is present, it is normally on the top of the barrel just forward of the receiver. Irksome (but forgivable) at times.

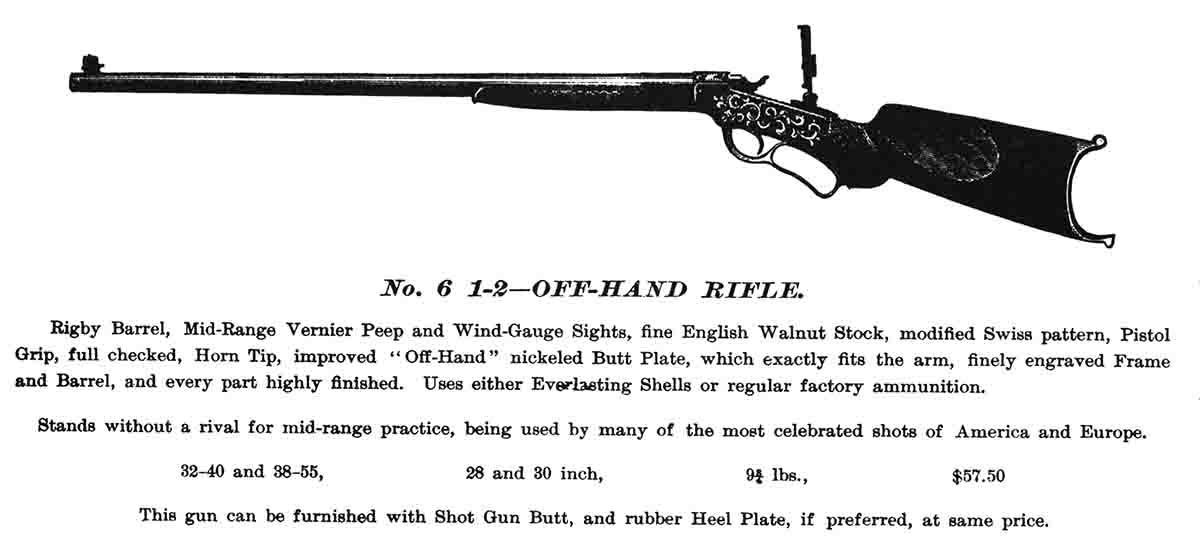

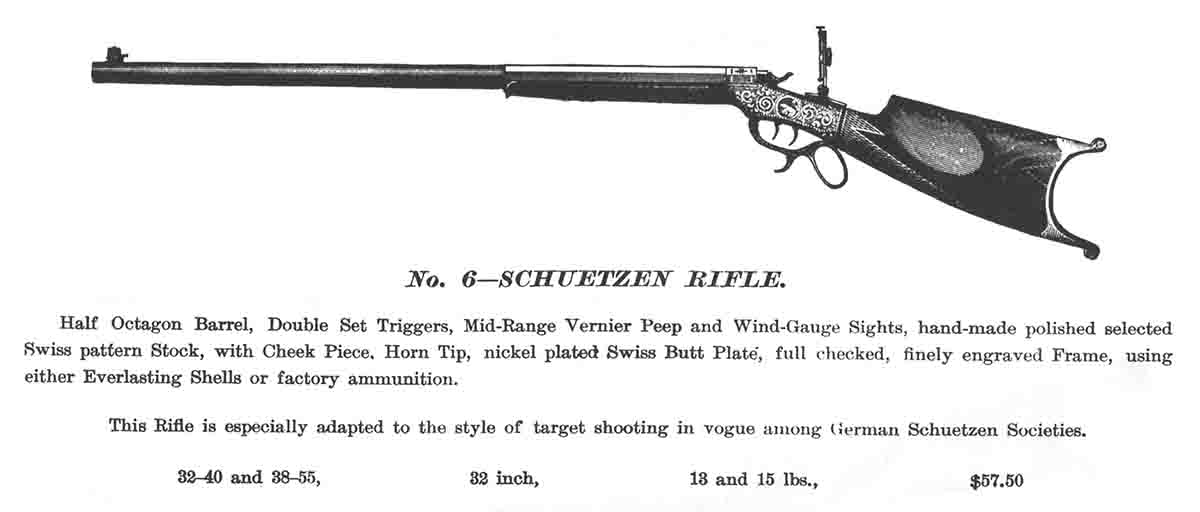

With its three-finger lever, single trigger and conservative Swiss-style buttplate, the 6½ Rigby was considered an “off-hand” rifle and thusly called by the manufacturer, as opposed to the closely similar Ballard No. 6 which was called a “Schuetzen” rifle. The No. 6 had a different lever style (usually a ball and spur), a reportedly excellent double-set trigger mechanism, and in most cases a half-octagonal barrel. The No. 6 is aesthetically a very close second to the 6½ Rigby. I am sure both the No. 6 and 6½ were used in Schuetzen competition back in the day, and probably so today.

Marlin produced four different Rigby models of the 6½. All variations contained similar characteristics, such as the engraved muzzle, hard rubber or horn forearm tip, engraved action, single trigger, upgraded wood with cheekpiece and Swiss butt, and, of course, the defining three Rigby flats. The first model had a straight grip and ring lever. Remaining models had a pistol-grip stock and a three-finger lever. The differences between the second through fourth models are very subtle. I believe mine is a third model. It also has a unique characteristic which I could only find referenced in George Layman’s book on Ballards. That unique aspect is the presence of a piece of horn or hard rubber at the rear end of the forearm where it abuts the action; a nice touch.

You may be wondering where the name “Rigby” comes in on a 100 percent made-in-America rifle. The answer lies in the three flat parts of the barrel where it meets the action. The barrel is a tapered round type except for the three flats which are about 2½ inches long and maybe 1⁄8 inch high. This barrel-design idea, where Rigby used one or more “flats” at the breech end of the round gun barrel can be found on many of the vintage guns and rifles made by Rigby of Dublin and London, especially on the percussion arms. These flats enhance the beauty of an otherwise mundane round barrel resulting in a really nice design feature. Another lovely feature of the 6½ Rigby Ballard action is in the receiver “bridge” which is octagonal in shape and is relieved on both sides creating what is called a “rebated frame” by Ballard collectors. The rebated frame style is also found on many other Ballard models. The edges or points of the octagonal bridge on both front and rear have been flattened on an angle or “faceted.” These facets are almost exclusively confined to the 6½ Rigby model. This is an incredibly well-conceived design feature which adds immeasurably to the overall beauty of the receiver. On some Ballard 6½ Rigbys, those little facet triangles have been engraved, as can be seen in Dutcher’s book in the 6½ Rigby section.

Another general feature of the 6½ is the grade of wood used in the buttstock, which is usually of high-grade English walnut, I am assuming. The example in this feature has really nicely grained lumber, as do most of those I have seen in book photos in my library or those for sale on the Internet. While we’re on the Internet subject, when browsing the various “guns for sale” sites, especially Guns International, you will discover that any No. 6½ Ballard for sale brings a pretty stiff price due to its scarcity. The subject of this feature was no exception and represents the most expensive domestic single shot rifle in my collection.

The forearm is long and slender, made with matching wood to the buttstock, with a somewhat complicated checkering pattern and a very nicely sculpted hard rubber or horn forearm tip – a standard feature on Marlin Ballard’s high-end rifles of the period.

The action is nicely engraved in a very large scroll pattern with two circular vignettes with images of a buffalo on the left side and a deer on the right; the animal subjects in these vignettes varied based on the engraver’s or customer’s choice. The actions were normally color case hardened. As can be seen by the photos, the color on mine has faded, though it is still a gorgeous rifle! The underlever for the 6½ Rigby was basically standardized with what is known as a “three finger” type. This is the most common lever found on these old rifles though there are special-order exceptions. The single trigger is, as I have encountered on Ballards regardless of model, as crisp and light as can be safely made.

The rifle has a Parts Unknown wind-gauge front sight that I added. The front sight that was on the rifle when bought had to be nonoriginal, as it was not consistent with the rifle’s overall quality and intended purpose. The rear sight is an original Ballard “improved” tang sight which has an elevation scale and no windage adjustment. These two sights make a

great combination for accurate shooting. This rifle is chambered for the .32-40, which was very popular for target shooting back in the day and still is. It weighs 9¾ pounds with a 28-inch barrel. The bore on the 6½ Rigby is perfect, with no evident problems that could be associated with a rifle of this vintage that was obviously well cared for.

Over 40 years ago, a Hensley and Gibbs mould was bought at a local gun show, even though at that time I had no rifle to use it for. I bought it based on the H&G name, which was constantly mentioned by Elmer Keith in his writings, with the inference that they were quality moulds. This one has two cavities for a .32-caliber 175-grain bullet with a spire point and gas check. As it has turned out, it is my go-to mould for all .32-40 applications and has consistently demonstrated its accuracy in several .32-40 rifles. It is especially accurate in my Ballard 6½.

This is the only bullet fired in this rifle since it was bought in early 2018. My first and only straight black-powder load, which has proven totally satisfactory, is 35 grains of GOEX 2Fg, slightly compressed under the gas-checked H&G bullet and no wad. It was modified into a duplex load, so I didn’t have to blow down the barrel after every shot. The duplex load is 3 grains of

W-231, 30 grains of GOEX 2Fg, and uses a large pistol primer for ignition; it works very well. This load is used for informal offhand shooting at a steel gong target at 90 yards at my unofficial shooting range south of my home. The rifle is truly a joy to shoot.