Fun with .32-Caliber Pistol Cartridges

feature By: Cody Smith | May, 19

The year was 1903. A man named Ed Smalley had recently been elected sheriff. Ed was not your typical Old West sheriff in that he had little experience in law enforcement. He had spent most of his previous life working in a mercantile store. He may have, in fact, been the stereotypical “shop keeper.” Regardless of who he had been, he was now sheriff of Laramie County, Wyoming, and on the morning of January 13, he had in his hand a warrant to arrest a man with a reputation for being one of the toughest, meanest, wiliest hombres to ever step foot west of the Mississippi River. That man was none other than Tom Horn, and he was being charged with the murder of 14-year-old Willie Nickell.

Tom Horn’s reputation was well deserved. Early in his career he was an interpreter and packer under the noted civilian scout Al Sieber on the Arizona Apache campaigns that brought in Geronimo. He was a top cowboy, winning many of the early rodeos in the West and he also worked in and owned various mines in Arizona. Tom was an active participant in the Pleasant Valley War of Arizona and is credited with being the cause of the disappearance of several people during that conflict. Tom then became a Pinkerton Detective Agency operative for several years and was mule packer in Cuba during the Spanish American War. What Tom ended up being most known for was his work as a hired gun for the large cattle interests in Wyoming.

At 11:30 in the morning, Tom was in the lobby of the Inter Ocean Hotel in downtown Cheyenne. He was waiting on a train that would take him to Montana to a new job and out of the reach of Wyoming authorities. Sheriff Smalley and his undersheriff approached Tom as he sat on a couch engaged in conversation with a Union Pacific detective. Tom did not appear alarmed by the approach of the lawmen, and he stood and stuck his hand out for a handshake. Sheriff Smalley said, “Hello,” reached out and quickly jerked the revolver from Tom’s waistband. Just like that, the tense moment was over, and Tom Horn was under arrest. Nobody had expected a man with Tom’s reputation to be so easily arrested by such an inexperienced sheriff, but that’s exactly what happened.

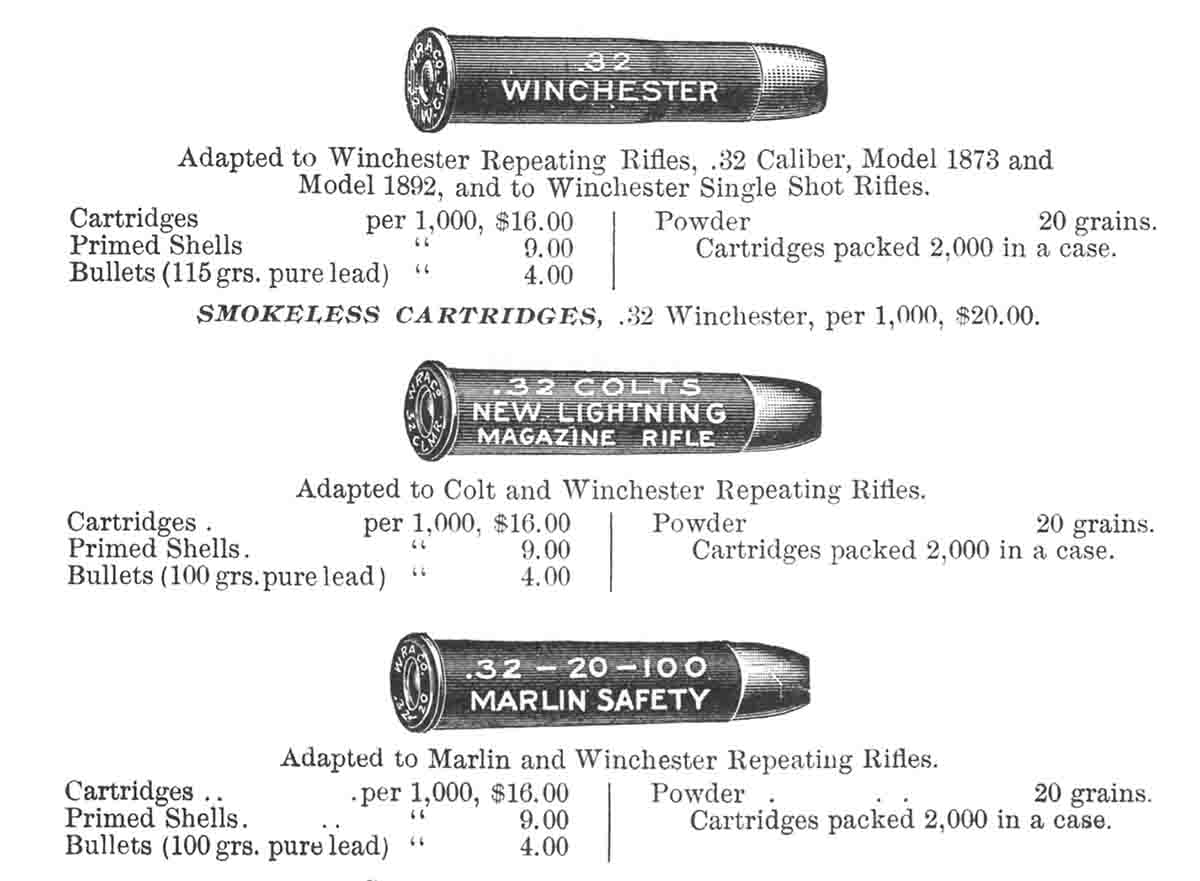

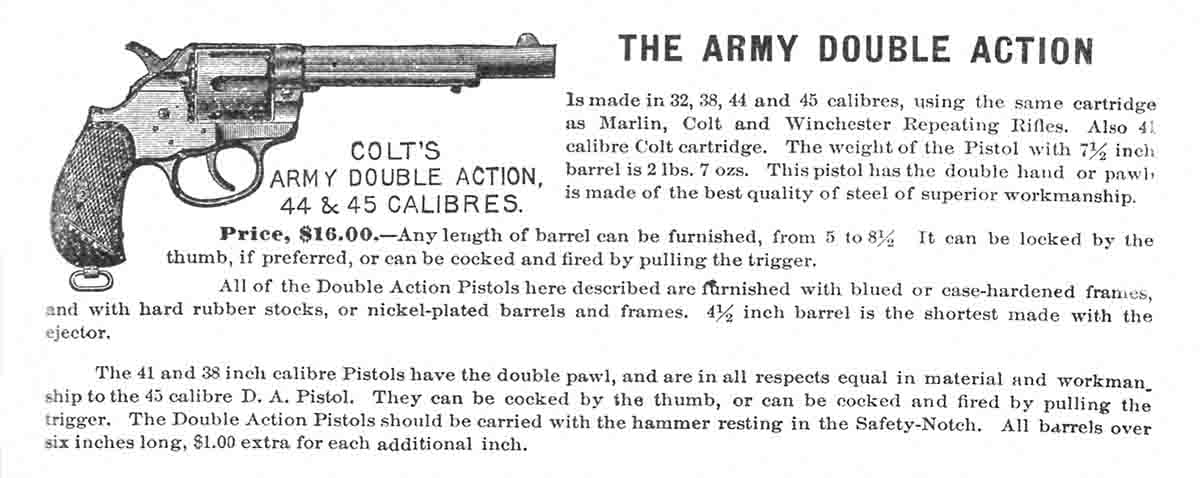

Boy, was I surprised reading that story! It piqued my interest and made me wonder about what kind of sidearms Tom Horn preferred to carry. Surely such a frontiersman would be carrying a sidearm as big and as powerful as possible, like a Colt Single Action in .45, or maybe .44-40 with a 7.5-inch barrel. Although the facts are vague about what exactly Sheriff Smalley took from Tom that morning, the story held more surprises upon further research. It appears Tom Horn was fond of carrying a Colt Single Action in .32-20 and other small-caliber weapons, as well as a double-action Colt in .38-40! Not being able to visit with Tom about his reasons for his choice in sidearms, we can only speculate.

Being of a young enough generation to have only viewed .32-20s as antiques, I thought I would investigate the characteristics and capabilities of modern versions of the .32-20, .32 H&R and the .327 Federal Magnum. I also wanted to load them with black powder and understand why Tom Horn had chosen to carry one.

Ruger introduced its Single-Six in .32 H&R Magnum when I was in high school. I remember reading about it in several gun magazines and thinking, that cartridge would really be the ticket. It appeared to be a light, handy and accurate revolver in a caliber that would have substantially more power than a .22 rimfire and could be reloaded for not much more money than purchasing .22 Long Rifle brass – I wanted one! It didn’t end up happening, and Ruger discontinued its .32 H&R chambering. Years later, Ruger released the Single-Six revolver in a .32 caliber again. This time, it was for a lengthened version of the .32 H&R and Ruger put seven chambers in the cylinder. This one didn’t get away this time, and as soon as I could, two Ruger Single-Seven revolvers chambered in .327 Magnum were acquired.

The two revolvers are configured quite differently; both are made of stainless steel, but one has a bird’s-head grip, a 3.5-inch barrel and fixed sights. The other has a traditional plow-handle grip, adjustable sights and a barrel that measures just a tick under 45⁄8 inches. I really like them.

The bird’s-head revolver is a nearly constant companion while making the rounds taking care of crops and cattle on the farm. It is easy to carry, fun to shoot, and packs considerably more authority than a .22 Long Rifle. I carry it in a cross-draw holster made by CME Holsters (cmeholsters.com). CME was a maker I had not heard of until recently. I have been very pleased with the company’s products, as they make quality holsters for a variety of guns. I thought CME’s prices were also quite reasonable.

I actually bought the plow-handled version a year or so before the bird’s-head revolver. It is quite similar to the .22 caliber Single-Six guns that many people are familiar with. I was not disappointed, as all of the thoughts from back in high school about the virtues of such a pistol turned out to be true. All of the handiness, pointability, and accuracy found in a Colt Single Action and the Ruger Single-Six were present. They are smaller than a full-size Ruger Blackhawk or Vaquero and are much easier to carry, but they are not so small as to be diminutive or hard to shoot. Most any prairie dog, jackrabbit, rattlesnake or coyote is in deep trouble if caught within appropriate range.

Although I had noticed the general publicity released with the new .327 Federal Magnum cartridge back in 2008, I did not pay a whole lot of attention until reading about the Single-Seven a couple of years later. The .32 case seems to just keep getting lengthened. The original .32 S&W case of 1878 was lengthened in 1896 to create the .32 S&W Long, and again in 1984 to create the .32 H&R Magnum. Although good in theory, the .32 H&R turned out to be a bit of dud, sales-wise, as pressures were held to maximum of 21,000 CUP due to the design of the H&R revolver for which it was developed. This was corrected when the .327 Federal Magnum was released as pressures are now held to a maximum of 45,000 psi. Full-power loads are definitely a handful and feel similar to shooting a .357 Magnum. The big advantage over the .357 was supposed to be that six cartridges could now be chambered in small-frame revolvers instead of the traditional five rounds. I suppose this is an advantage, but anyone who has fired full-power loads in a snubby revolver can attest, there is often more hope in making your opponent deaf than actually hitting him.

A subject not often mentioned when discussing “easy packing” revolvers is the fact that chance encounters with varmints of either the two- or four-legged variety seldom wait for one to install hearing protection. Don’t get me wrong, I am an adamant believer in using hearing protection. There are multiple pairs hanging from the mirror of every one of our vehicles and I require their use by any employees or folks using our ranges. The truth is, however, that often days or weeks go by without firing a round, but then Mr. Coyote makes a surprise appearance and there are often only seconds to fire an accurate shot. Hearing protection is usually left out, and because of this, I avoid high-power revolver loads. Shooting full-power .327 Magnum loads out of a revolver with a 4-inch barrel without hearing protection is something akin to cramming a pencil into your ear; painful, stupid, and debilitating for sure. Because of this, I have become a fan of mild .32 or .38 loads. They are still much louder than should be routinely shot without ear protection, but an occasional round here or there doesn’t seem to hurt much. They are also still plenty powerful to do the job intended and are much easier to shoot accurately.

The third addition to my .32-caliber arsenal was the result of a lucky chance encounter at a local gun show. I happened to bump into an 1894 Marlin in .32 H&R Magnum. According to my research, only about 600 were made in 2005 and 2006. They are also a bit odd in that the rifles are the only centerfire Model 1894s that I know of that do not have the side loading gate. They must be loaded through a port in the magazine tube near the end of the barrel like most tube magazine .22 Long Rifle guns. The price was quite reasonable, and the rifle had been shot very little. I snatched it up and have really enjoyed it. The mild loads out of the 20-inch barrel are pleasant to shoot and it has made a handy and very fun accomplice to my two Single-Sevens.

As always, the reloading and range time spent in developing this article was quite enjoyable. I had two moulds to cast bullets for testing some black powder loads in both the .32 H&R and the .327 Magnum cases. These loads were compared to my standard load of 6.5 grains of Accurate No. 9 behind a 100-grain roundnose/flatpoint commercially cast bullet and a CCI Small Pistol primer in a Starline case. This load consistently prints sub-one-inch, 5-shot, 25-yard groups from the rifle and around 1.5-inch groups from the 45⁄8-inch barreled revolver. Velocities averaged 1,137 fps from the rifle and 842 fps from the revolver.

15 grains of Swiss 3F in the H&R case and 17 grains in the .327 Magnum case nearly fill it to the top. The charge is then compressed and the bullet (lubed with Rice lubricant) is seated. The two moulds I had on hand were a roundnose and semiwadcutter. The roundnose bullets were cast from a Lee No. 90301 double-cavity mould. Using 20:1 alloy, it threw bullets weighing 101 grains and measured .313 inch. The semiwadcutter bullets were from a RCBS 32-098-SWC double-cavity mould. With the 20:1 alloy, they weighed right at 102 grains and measured .315 inch. No wads were used.

Although I have shot thousands of rounds through my BPCR rifles, I have not shot black powder in revolvers very much. I don’t know why I was surprised, but the large amount of smoke that was created when firing a round was rather astonishing. Besides the cloud that came out of the end of the barrel, it seemed like a lot vented out from the cylinder gap. As can be seen in the photos, heavy smoke deposited a coating of fouling over the cylinder and frame of the revolver. It was a very enjoyable experience that I will no doubt be doing again, but it really brought to light the struggle the old guys faced in trying to keep their firearms in good working order. I have always thought our BPCR rifles were simple to clean and maintain, but I found out that the revolvers were a different matter. It just took a few minutes in the comfort of my basement, but when one considers how it would have been done along the trail, you realize the commitment that was required.

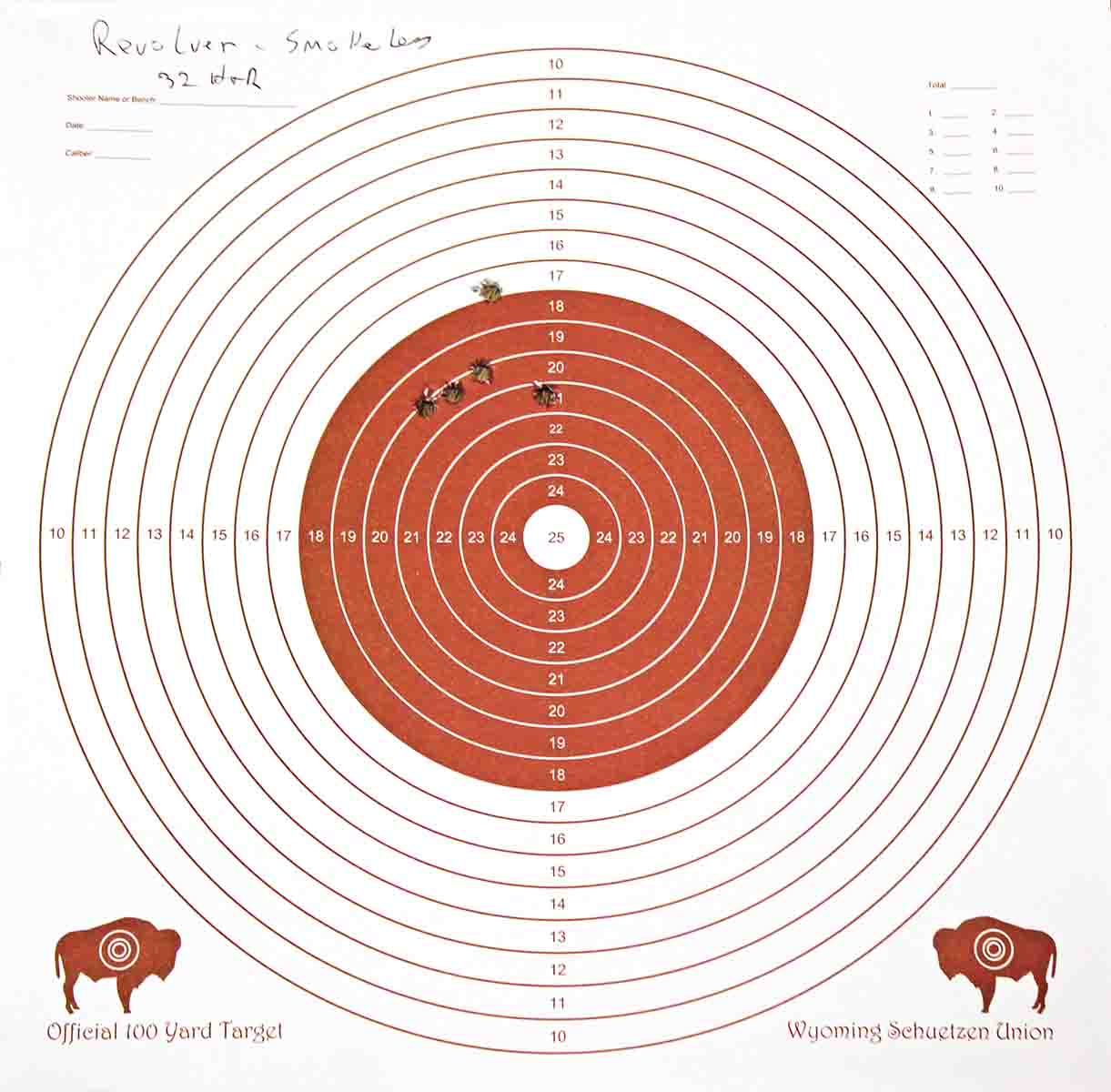

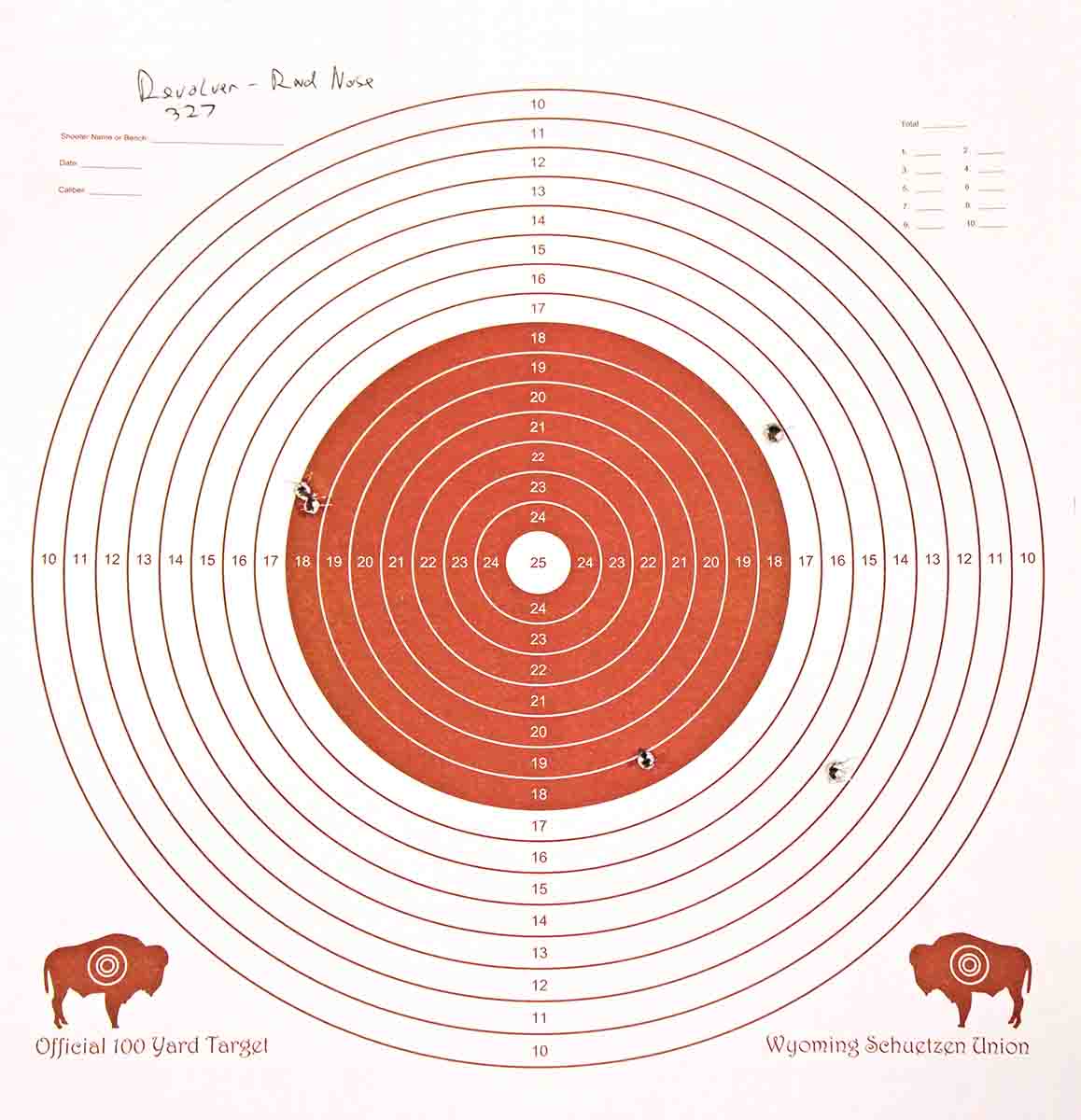

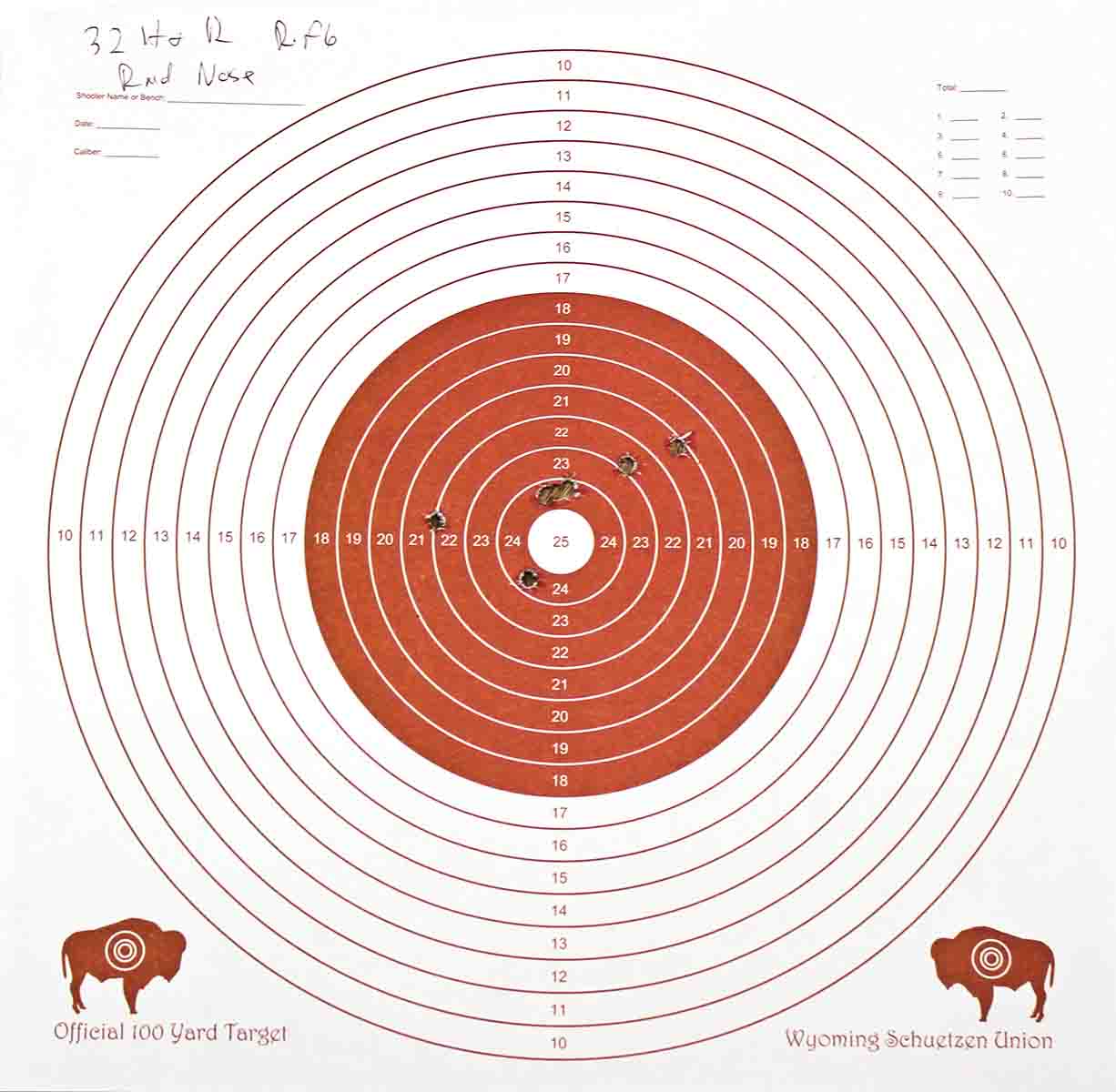

In the revolver, .32 H&R cases proved really inaccurate. I would suppose the short case in the longer chamber was the cause, but not all five rounds would hit the 12-inch target at 25 yards. Switching to the .327 Magnum cases substantially improved accuracy. Groups were still not very good, but the semiwadcutter seemed to have an edge over the roundnose, which was the opposite of the rifle. Semiwadcutter groups averaged about 6 inches at 704 fps, while the roundnose averaged about 7 inches and registered 715 fps. Although the revolver and my hands were covered with black powder fouling after about 75 rounds, the fouling did not stop the functioning of the revolver. Like the rifle, accuracy also did not seem to substantially decrease after that many rounds.

Larry Ball is an expert on Tom Horn and the author of the book, Tom Horn in Life and Legend. I had the pleasure of visiting with him recently. Larry had some thoughts on Tom’s choices of sidearms and I have to agree with his ideas. Larry concluded that Tom just liked guns. He was known to own quite a few different guns throughout his career and often had some of the newest guns and loads that were available. Whatever he was carrying that day may have been the result of a whim while at the local gun shop. Or, just maybe, he happened to read an article in a magazine and thought to himself, A .32-caliber revolver? Man, that would be just the ticket! I am sure all of you can understand.