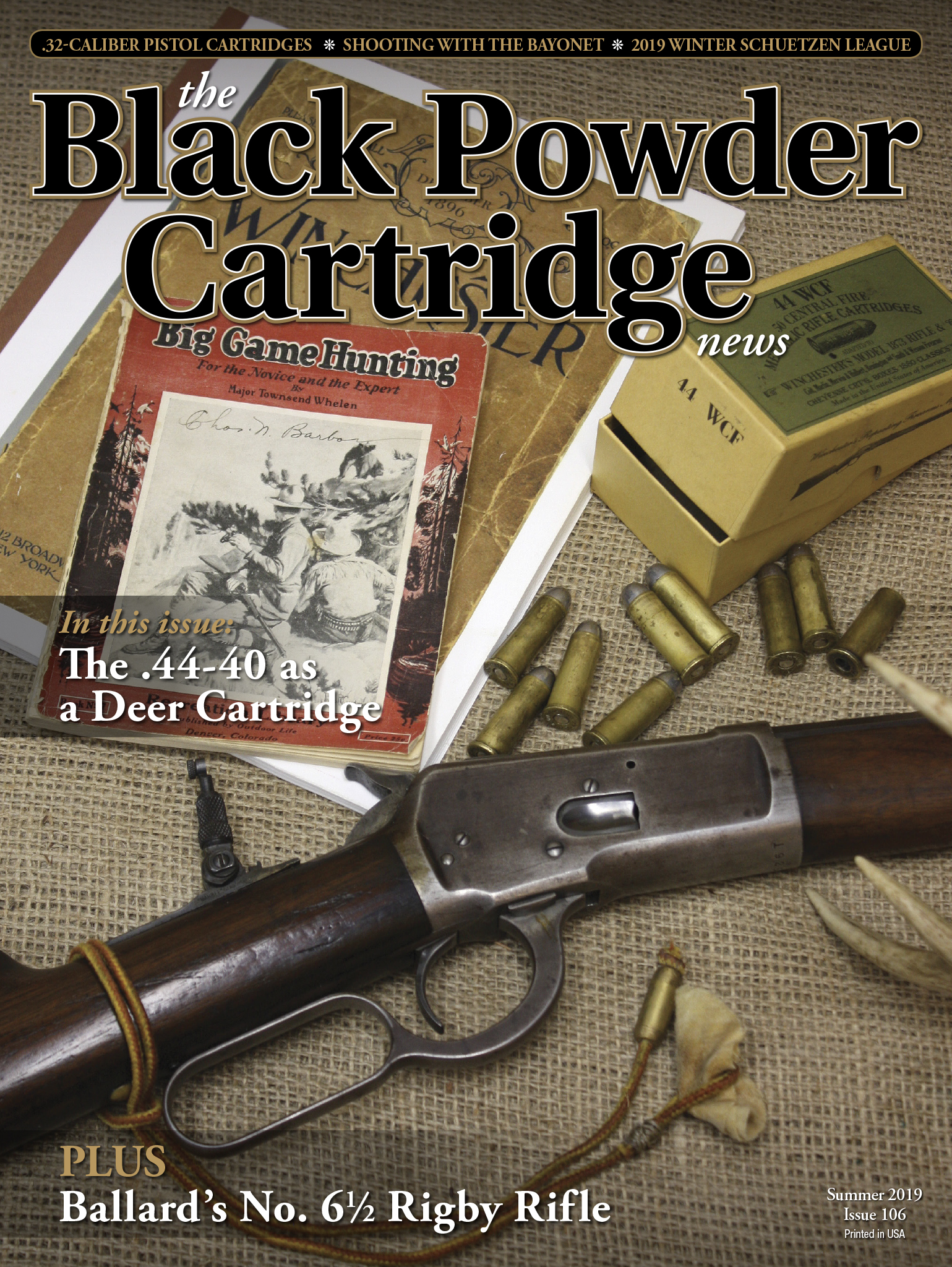

The .44-40 as a Deer Cartridge

feature By: Harvey Pennington | May, 19

Recently, I decided to take an old friend on a deer hunt in Kentucky. The “old friend” was a Model 1892 Winchester that had been manufactured in 1902, and it was with that .44-40 rifle that I harvested a young whitetail buck in northern Maine about 40 years ago. That was my first hunt with a true black powder cartridge rifle using black powder loads, and I’ll never forget the experience; you see, that hunt with the old .44-40 rifle stirred something in me that is very special, even until this day.

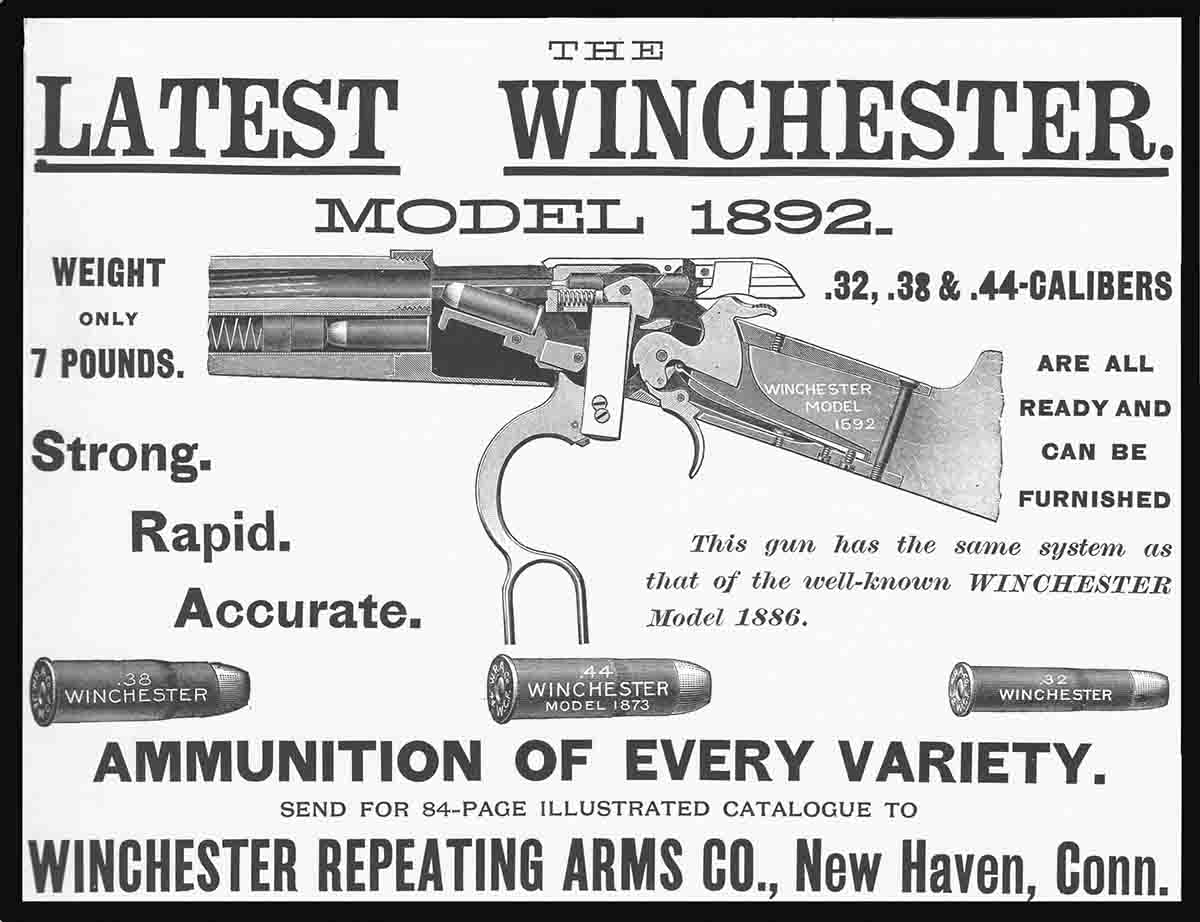

Actually, my ’92 Winchester was originally chambered for .38-40 WCF (.38-40), but when I purchased the rifle in the late 1970s, the bore of the old rifle’s 24-inch barrel was terribly pitted and would not shoot cast bullets with any accuracy at all. However, since the rifle was otherwise in great shape, I decided to have the original barrel re-bored to .44 WCF (.44-40) and shipped the old ’92 to Bob Snapp a Michigan gunsmith to do the work. He did a beautiful job.

The UMC cases were the old “balloon head” type, which were typical of early black powder loads. Allow me to include a warning here: such old-style cases are thinner and weaker than modern “solid head” cases available for the same caliber and should be carefully checked for soundness before even being considered for use in reloading. Any cracked or otherwise unsound case should be immediately discarded. Those remaining cases that are in good condition should be loaded with black powder loads only; they should be considered too weak for use with smokeless powder reloads.

The average weight of the powder charge in each of the old UMC cartridge

cases was about 36 grains, and the granulation of the black powder used in those old factory loads appeared to be FFg. Of course, I did not know when the cartridges had been manufactured, but the powder showed no signs of being deteriorated, or “caked.” The bullets in the old rounds were very soft (probably pure lead), and the bullet itself appeared to be a perfect match for those cast in my Lyman No. 42798 mould. The factory bullet lube also appeared to be in good condition.

By the way, I did take time to chronograph a few of the original UMC cartridges; the average velocity was 1,220 fps, and they were very consistent from shot to shot. That velocity was essentially the same as those published in the 1896 Winchester catalog which listed velocity of its .44-40 as 1,245 fps.

For the hunt in Maine, I wanted to reload as traditionally as possible, so I chose to use the old UMC cases. I used CCI Large Pistol primers which measured .120 inch in thickness, and when seated were slightly beneath the level of the case head. CCI Large Rifle primers were thicker – about .128 inch – and, at times, protruded slightly above the case head when seated. I believed this could possibly lead to an accidental discharge when the cartridges were cycled through the rifle’s action, so I used the pistol primers for all loads in the .44-40. Besides, I reasoned that the relatively small black powder loads were better served with a milder primer.

Of course, I used the Lyman No. 42798 cast bullet using 1:40 (tin-to-lead) alloy. The bullet’s as-cast diameter was .431 inch, and required no sizing at all for the .429-inch groove diameter of the barrel. The lube that was used back then was three parts mutton tallow, to one part beeswax. The mutton tallow came from a farmer friend who kept it on hand to help waterproof his boots. It worked just fine.

Accuracy of that load was under three inches at 100 yards, without wiping or blowing between shots. I chronographed the loads at 1,219 fps, which was virtually identical to the velocity of the old UMC loads.

On the ensuing hunt in Maine with partner Arville Allen, I managed to take a small buck at about 30 yards with the .44-40 while still-hunting on a snow-covered ridge. The deer was standing and quartering toward me. The bullet hit behind the shoulder on its right side, but because of the angle at which the buck was standing, the bullet exited the left hindquarter. Even though it was a fairly small buck, that amount of penetration was surprising. The buck had fallen at the shot but got up and fell dead after traveling no more than 20 yards.

As stated earlier, the hunt in Maine took place about 40 years ago. Recently, though, I had an urge to forego using larger black powder cartridge rifles (such as the .38-55, .40-65, .45-70 and .45-110) in favor of using that trim little ’92 Winchester again during the 2018 deer season in Kentucky.

Of course, much of the popularity of the old .44-40 had to do with it being chambered not only as a rifle cartridge, but also as a handgun cartridge. So, perhaps I should mention one other deer that was taken with a .44-40 about 10 years after the Maine hunt: it was a whitetail doe shot with a 4¾ -inch barrel Colt Frontier Six Shooter, manufactured in 1903. I was using smokeless loads with Unique powder; velocity of the No. 42798 bullet was about 830 fps. The doe was only about 25 yards away and facing me when I shot. The bullet struck in the center of its chest and the doe managed to run only 25 to 30 yards before falling.

Having said that, it is important to point out that at that close range and with the steady rest at the time, I felt confident about the shot or I would not have taken it. Nevertheless, the incident serves to show that the .44-40 handgun can still effectively manage to provide venison for its owner under the right circumstances.

Now, I don’t think it would be an exaggeration to state that most of today’s shooters are only acquainted with the .44-40 as a cartridge for use in cowboy action matches. Most of the cartridges used in that type of competition (at least in our area) are intentionally underloaded with light charges of smokeless powder – just enough to make the steel targets ring, and to allow the competitor to quickly recover for speedy follow-up shots. All of that is fine for such competition, but such light loads certainly do not promote an accurate appreciation of the .44-40’s true potential as a close-range hunting cartridge.

In 1923, Outdoor Life published a little book written by Townsend Whelen – a true hunting and firearms expert if ever there was one. It was titled, “Big Game Hunting For the Novice and the Expert.” In that little volume, Whelen – classifying the .44-40 as a deer cartridge – recommended sighting it for 100 yards and gave it an “accuracy range” of 150 yards. It is quite revealing that Whelen included that information in 1923 – almost 30 years after the introduction of the much higher velocity commercial smokeless hunting cartridges like the .30-30 and .303 Savage. It shows that even at that later date, the old black powder cartridge still had a following.

In another of his books The Hunting Rifle published in 1940, Whelen lists having taken two deer with the .44-40, each with one shot. So, unlike other writers who never really used the .44-40, he was speaking from experience, not just from theory or hearsay.

Another well-known user of the .44-40 Model 1892 Winchester was the adventurer/explorer Commander Robert E. Peary, who stated that he depended on that rifle to provide fresh meat like deer or seal for his men on expeditions to places like Nicaragua and the Arctic.

I certainly agree with Townsend Whelen that the appropriate sight-in distance for the black powder .44-40 would be 100 yards, and that is what I use. When sighted for 100 yards, the midrange trajectory of the bullet is only 3½ inches, certainly not enough to cause the hunter to overshoot a deer at 50 yards. But, it is not a hunting cartridge to be used at distances much greater than 100 yards. For instance, when sighted in at 100 yards, a shooter can expect the bullet to strike about 10 inches low at 150 yards because of the rapid velocity loss of its short, flatnose bullet. However, when used for deer within the shorter ranges for which it was intended, its effectiveness cannot reasonably be questioned.

Well, as the 2018 Kentucky deer season neared, I began to prepare. I still had nine of the old Remington/UMC cases that were still in good shape and naturally wanted to use them. Again, 36 grains of GOEX FFg powder was loaded, and CCI Large Pistol primers were used. Of course, I stuck with the Lyman No. 42798 bullet, and the 1:40 alloy, but changed the lube to a homemade mixture that I now prefer; weight of the finished bullet was 217 grains.

In a short session at my home shooting range, I found that the 100-yard zero of the old rifle with its Marble tang sight hadn’t changed a bit. So, I felt the Winchester ’92 would be ready when the season opened.

As usual, when hunting season began, things didn’t work out as easily or as quickly as I had hoped. The weather turned rainy, and other nonhunting obligations had to be met. But, on the next-to-last day of our deer season, a nice 8-point buck came strolling past me at a distance of 50 yards, offering a perfect broadside shot. It was a dim, drizzly morning, but when I was sure of the sight picture, I fired. The buck took off on a frantic 50-yard run and fell dead at the base of a small oak tree. The bullet had struck just behind the left shoulder (exactly where I intended), passed completely through its chest, and exited behind the opposite shoulder. Once again, the old cartridge had performed well at short range and had effectively helped fill our freezer.

The .44-40 is a historic cartridge whose heyday was from about 1873 until the mid-1890s when the higher-velocity, flatter-shooting, smokeless powder cartridges were introduced. But, when used within the close ranges for which it was intended, and when the shot is placed where it needs to be, that old cartridge will, with certainty, still provide the venison.

References:

Madis, George. The Winchester Book. Art and Reference House, Brownsboro, Texas, 1979.