Barrel Length and the 44-40

feature By: Mike Nesbitt | March, 25

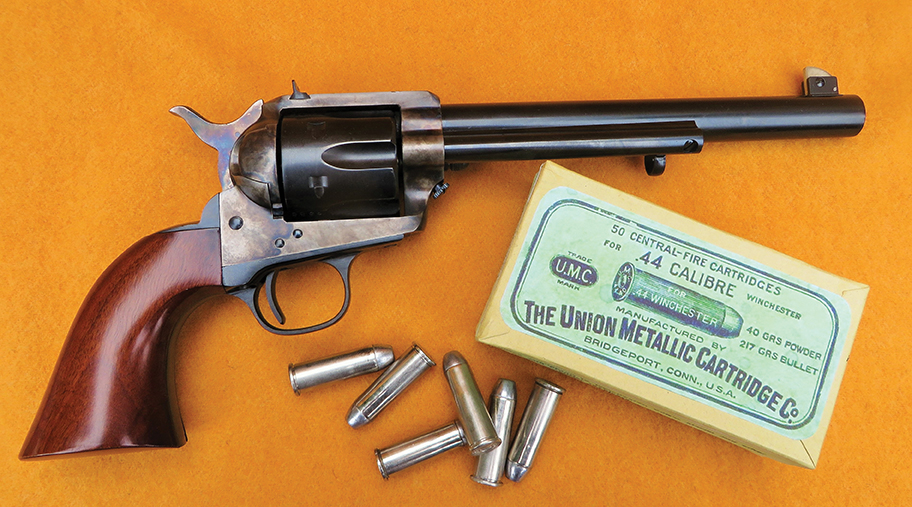

You might ask, “Why do this with the 44-40?” Let’s remember that the 44-40 was America’s favorite cartridge until that honor was passed on to the 30-30, in what we can call “another era.” Another point favoring the 44-40 was that it could be had in rifles, revolvers and even single-shot shotguns. The 44-40 was actually very popular around the world and it has been said that the 44-40 has killed more game, both big and small, and more people, both good and bad, than any other cartridge from the 1800s. To cover the practical side of things, between my friends and I, we had the widest variety in barrel lengths with our 44-40 rifles. So, the 44-40 was a very easy choice to make.

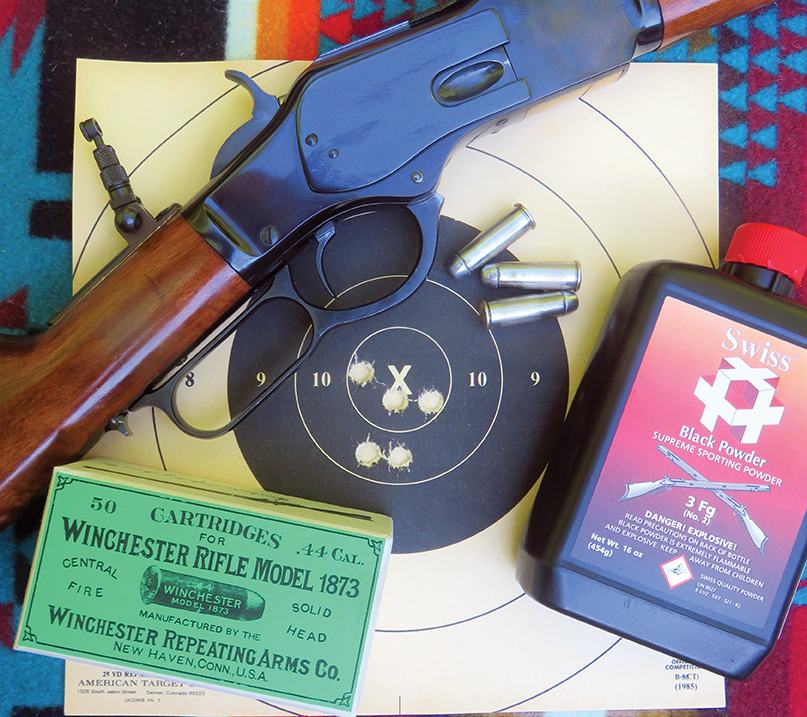

The powder charges were all the same, using Swiss 3Fg powder, except for just a couple of shots taken with another grade of powder for comparison. Those powder charges were not individually weighed, but the powder measure was set for 35.0 grains and checked occasionally as the loading continued. All loading was done at one sitting, so the powder measure was never re-set for this particular batch of cartridges and all of the powder used came from the same can of powder. This amount of powder in a 44-40 case requires some compression and for these loads, the powder was simply compressed with the seating of the bullets.

Priming was all done using CCi Standard Large Pistol primers. No Magnum primers were used to “help” the powder develop higher speeds. The brass cases these loads were contained in were all from Starline, once-fired, nickel-plated 44-40 cases that were in good condition.

In order to further consistency, we would need to do all of the shooting with just one gun, or one gun barrel, cutting that barrel back to make a different length after each test firing. Please forgive us for not doing that! We used a different rifle for each length tested, so maybe this is a “hole in the soup” for our conclusions. If there can be any consistency in our tests, all but one of the rifles that we used were made by Uberti with Uberti-made barrels. The single “odd ball” was my Low Wall in 44-40, which was made by C. Sharps Arms with a Green Mountain barrel. While our variety in rifles means our testing was not completely uniform, we feel that it was close enough to make our conclusions worthy and reliable.

In addition to all of that our shooting was done on the same day. This simply means there was no real variation in temperature or air pressure, two things that can affect the velocity of a bullet. And, while this might not have had any effect on the velocities that we gathered, all of the shooting was done by the same shooter, Allen Cunniff. Our “team” was made up of four people; I was the note-taker, Jerry Mayo was the observer (who read the chronograph readings through binoculars), Dan Johnson was our target man (changing targets after each five-shot string), and Allen Cunniff was our shooter. We did things that way just to help with the consistency of our testing.

One little difference in our loads, other than the granulation of the powder, was that Allen sized his bullets to .430 while mine were sized to .429 diameter. In general, the larger diameter should have raised pressures slightly. For now, we can only guess at how this small difference might affect things; even his homemade bullet lube could affect the bullet velocity. For our rifle shooting we only used my loads with just one single exception, which will be pointed out.

Moving up to an 18-inch barrel, five more shots were fired at another target. This rifle, one of the Cimarron “Brush Poppers”, was not equipped with a tang sight. Instead, it had the open sight on the barrel as equipped from the factory. With that open sight, this gun did not perform with the same accuracy as the Trapper, but with the two-inch longer barrel it did have a higher velocity. Bullets from the 18-inch barrel stormed across the chronograph at 1,278 fps.

Following that, a 20-inch barrel was tried. For these shots, another Uberti was used, this one a copy of the Model 1866, a Short Rifle. While this gun’s barrel was only one inch longer than the carbine’s which was fired just before trying the 1866, the velocity from the 20-inch barrel averaged one foot per second slower than the 19-inch barrel. For this study we were generally only looking at averages and those averages were based on only five shots. Consequently, that’s a very small sample size for such tests. Among the shots fired through the 20-inch barrel we found the highest recorded speed to be 1,309 fps, which is nine fps faster than that fastest speed noted from the 19-inch barrel. Also, the five shots fired through the 20-inch barrel included the slowest velocity recorded, 1,277 fps. This one individual slow shot is what made the average velocity for the 20-inch barrel slower, again by only one foot per second than the average for the 19-inch barrel.

To check on that, the lowest velocities for both the 19 and 20-inch barreled guns were thrown out and the remaining four shots from each rifle were averaged. By eliminating those slower shots, the average speed from the 20-inch barrel was one foot per second faster than the four-shot average with the 19-inch barrel.

However, greater differences were soon noticed. The next rifle we tested was another Uberti Model 1866, but with a 24-inch barrel, a full-sized rifle. From that gun, five shots with the 35 grain loads of Swiss 3Fg produced an average velocity of 1,324 fps. Interestingly, that’s getting in line with the advertised velocities of over 1,300 fps for the old black powder 44-40s.

While the jump in velocity from a 20-inch barrel to a 24-inch barrel was about 30 feet per second, and as we checked the velocities with even longer barrels, the bullet speeds did increase but not as much. Even so, the bullets’ velocities did keep on increasing and we did not encounter a barrel that was too long or a point where the bullets would peak at a velocity and then slow down as the barrel length was increased.

Going to the 26-inch barrel on an Uberti Highwall, the velocity increased basically 10 feet per second with an average of 1,333 fps. When the 28-inch barrel was tried, in the Low Wall from C. Sharps Arms, the velocity jumped about another 10 feet per second; that average was 1,341 fps. Those averages easily fall within what we expected and we were enjoying the performance.

After Allen had fired a group with the Low Wall, I asked him if he had used the gun’s set trigger. I had thought that the group should be somewhat tighter and using the set trigger could certainly help. Allen replied, “No, I forgot that it had a set trigger...” His group was still a good one, but we were actually more concerned with average velocities than group sizes.

Those averages were being figured out while we shot and after seeing the average velocity for the 28-inch barrel, we were more than ready to try what we might call the “ultimate 44-40.” This rifle was the Uberti copy of the Model 1873 Winchester with the 30-inch barrel, the 44-40 of mine that I have used most often, with the best success when counting hits on the trail or scores on paper targets. To get a better idea or a more accurate average, this rifle was used to send bullets across the chronograph 10 times rather than just five, for a nice 10-shot group. Once again, the average velocity jumped by about 10 feet per second, now up to 1,353 fps. The group fired was very pleasing, all 10 shots nearly cutting a jagged hole near the center of the target, with just a couple of shots missing the X-ring.

Our only real conclusions to these tests, apart from getting the average velocities from the array of barrel lengths, is that Swiss 3Fg powder gives greater performance than the other powders with coarser granulations and that increased barrel length certainly has a performance advantage. From the 16-inch barrel to the 30-inch barrel we saw an average velocity increase of over 100 feet per second. Whether or not that advantage is offset by the convenience of the short carbine is up to each shooter. I know I’ll still be shooting with both my 16-inch and the 30-inch barreled rifles, all depending on where and what for. It is good to actually know just how much difference the longer barrel makes.

.jpg)