Captain Jack

feature By: Jim Foral | June, 24

The people marveled that anyone could snipe thrown marbles, coins, or other small objects out of the air and do it without a bauble, miss, or hesitation. The demonstrator could then artfully trace outlines of Indian heads or Buffalo Bill on a sheet metal canvas with their rimfire paintbrushes, or unerringly smash a stacked handful of flung clay pigeons and leave no survivors. The best of these performers could do this from the back of a galloping horse or from a speeding automobile.

During the heyday of the exhibition shoots and exhibition shooters, the performer’s skill ranged from very, very good to positively spectacular. Their lasting notoriety favored those with corporate backing, such as Winchester’s Topperwein husband and wife team. A household name yet, Annie Oakley, was acclaimed first for her skill and then for her well-promoted novelty as a female.

In every field of human endeavor, certain individuals will establish themselves at the top of their kind. The destiny of the others has always been to be at a location on a somewhat lower rung, where there is a lot of room. Of those trick shooters less than supremely talented, less noticeable or publicized, who made a living at the trade are still interesting human beings with stories to tell. Among these was Jack O’Connell.

He put in a stint of frontier law enforcement and was involved as a member of a U.S. Marshall’s posse in a fight at the Little Missouri in 1885, an attempt to clean up the rowdy cowboys at the famous ranch of the Marquis de Mores, the nemesis of his neighbor Theodore Roosevelt. Jack remembered T.R. as the greenest tenderfoot – “specks and all”. He further remarked that there was something about the man that commanded respect. Reading between the lines, during his time in North Dakota, Jack experienced what it was like to be shot at.

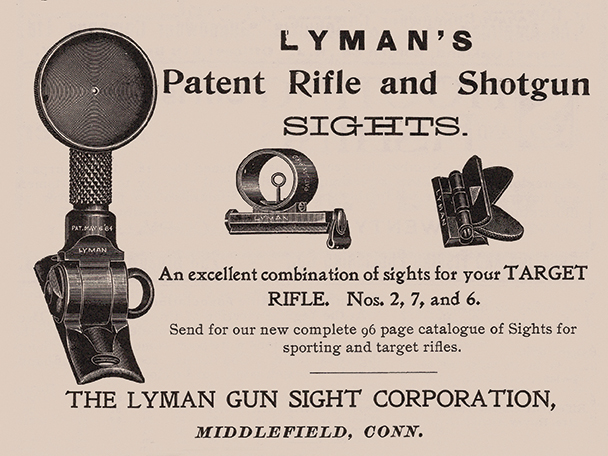

Amongst his boyhood peers, Jack always enjoyed his reputation as a good kid with a rifle. In 1878, William Lyman gave Jack his first break by hiring him to publicly demonstrate Lyman’s tang mounted peep sight, which at the time made “wing shooting with a rifle” not beyond the sight’s scope of usefulness. Jack O’Connell toured for Lyman and put on demonstrations of what could be done. He was instrumental in William Lyman’s initial success and getting the merits of the Lyman system established in the minds of American riflemen, and himself as a naturally gifted talent as a rifle shooter, as well as a budding showman.

Jack’s early professional experience was more far ranging than any of his counterparts. After William Lyman was off and running, Jack toured with the Kohl and Middleton Dime Museum. The popular dime museums were considered entertainment for the working class in the 1880s, and they were also considered a springboard for performers hoping for better. Harry Houdini got his start in just such a venue.

Jack then did a tour with the Pomeroy and Hilton’s Wild West Show, one of the more obscure of its type. At 24, he shot in front of throngs of people attending the 1884 World’s Fair in New Orleans. The next year, he went on the road with the ambidextrous, American-born Chevalier Ira Paine, the man who made a career of outshooting the rest of the world, and acclaimed as “King of the Pistol”. He and Jack appeared in front of the notorious King Leupold when they performed at the Antwerp, Belgium World’s Fair. It was said they shot “at all the world’s capitols”. Jack toured Europe with Doc Carver for many months, challenging all comers.

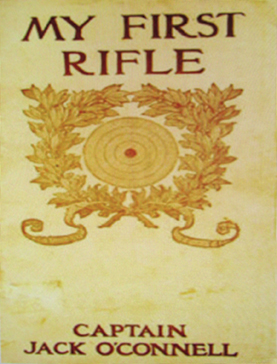

The November 1905 issue of McClure’s Magazine carried a Hopkins and Allen Arms Company ad, offering a booklet titled My First Rifle by Captain Jack O’Connell, “the famous rifle shot, late of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show”, and specified that it was “free upon request”. Captain Jack’s first rifle was an H&A rim-fire model, and he and the gun maker seized the opportunity for mutual self-promotion. The booklet of a few pages contained some of Jack’s background and some trumpeting of the gun maker’s goods. This included a seven-shot, spur-triggered revolver chambered for 22 Short. Its frame carried the logo of its model – “Captain Jack”.

This era’s exhibition shooters understandably drew their stunts from a common and limited bag of tricks. Thus, the repertoire of each was essentially the same, though it could vary in sequence. The staples were few, actually. Plucking small objects from the air was satisfying to the crowds but this was quickly overdone to the point of boredom. But it seems that they all could accomplish this expertly and they all knew when to move on. Shifting gears to drawing a person’s profile with a .22 repeater was also “done to death” in due course.

Shattering blue rock, even rapid firing at bunches of them only satisfied for so long before it became monotonous. It seems that the shooters that lasted in the profession were roughly similarly skilled. Those that had to wonder if they had what it took got weeded out pretty quickly. Captain Jack was as proficient as any of his trick shooting peers at pulling off the standard tricks of the trade. Showmanship varied in degree and this quality separated the popular from the also-rans.

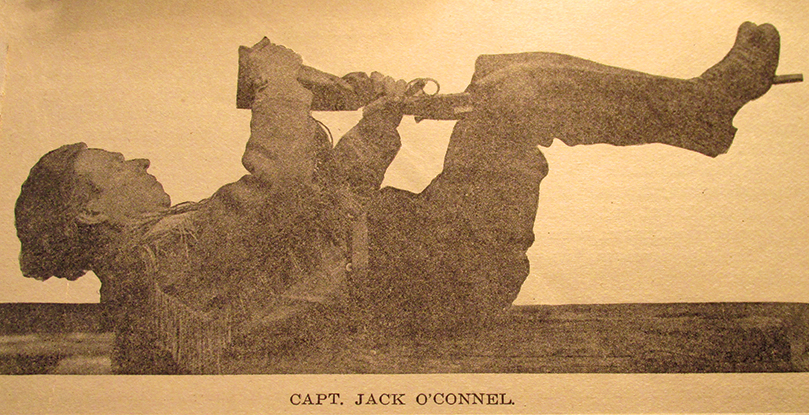

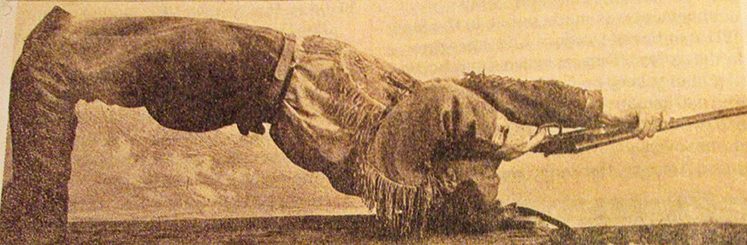

It didn’t hurt to have a gimmick to set him apart from his less flexible counterparts. Jack had a signature stunt original and unique to himself. He’d lay on his back, clutch his special order five and a half pound Ithaca side by side between his knees, and thusly contorted, sight along the inverted rib and press the trigger with the pinky of his left hand. He could go 25 straight from this position. A variation involved placing both of his feet and head flat on the ground, and with a fully arched back, sight along the same upside-down rib.

Just as auctioneers have chosen to dignify themselves with the lofty honorary title of “Colonel”, the brotherhood of trick shooters chose the less pretentious designation of “Captain”. All but Mrs. Topperwein used it.

There was at the time a terrific fascination with trick shooting among the readers of the sporting magazines. The editors encouraged the professional shooters to submit tips to teach this, as best as a hands-off approach would allow. Captain Jack got the ball rolling with "How to Become A Crack Shot," which appeared in Outers Book for April of 1907. Most of Jack’s more notable contemporaries followed suit and provided similar written tutelage. George Bartlett and A.H. Hardy, who both represented the Peters Cartridge Company, contributed their might. Capt. Hardy, who called what he did “expert fancy shooting” also churned out a three-part series with the title, "How to Become A Crack Shot," which began in the September 1909 issue of Outdoor Life magazine. Adolph Topperwein’s tutorial took the whole of three-monthly installments in Outdoor Life. His wife Elizabeth, counted among the great trapshooters of the day, did the same with one over-simplified lesson.

It would appear that Marlin’s lever action Model of 1897 .22 was preferred by most of the exhibition shooters. The ’97 was accurate, smooth and quick in operation, and its tubular magazine held a lot of shells. The Marlins of the trick shooters were typically high-grade guns with the owner’s name engraved on the flat receiver, and surrounded by a generous amount of artful engraving. The suspicion generally is that these guns were presented (given) to the shooters with the expectation that they would be publicly seen. Captain Jack spoke very highly of his. After putting 500,000 shots through it, the gun was still tight and accurate, though it showed handling wear.

The December 1912 issue of Outers Book posted an ad in its classified section to sell an assortment of 20 guns owned by Capt. Jack O’Connell of Rapid River, Michigan. This number included a Savage Model 1899 30-30 (but not the lavish engraved .303 Savage presented to him by Savage). There was a Savage .22 autoloader with a Maxim silencer, and a “finely finished” pair of “Batavia” .22 self-loaders, each having the silencer. There was also an assortment of quality revolvers and automatic pistols. Jack made the additional investment of three cents for each of the following words: “Above arms owned and sighted and guaranteed perfect by an expert of national reputation.” Readers of his terms may have sensed an urgency together with a need: “Spot cash, no trades.” Offered as a possible explanation or reason was this bewildering revelation – “Right arm paralyzed.” Jack’s unrevised ad ran through the March 1913 issue of Outers.

Apparently, out of commission in the trick shooting business and no longer in the public eye, Captain Jack proceeded to get by as best he could. He was known to have operated a shooting gallery in Ecanaba, Michigan, from 1918 to 1922. He married in 1920, and fathered a son, fittingly named William Cody O’Connell. Later, his family moved to Bemidji, Minnesota, where he operated a gun repair shop. Through the ‘teens and early 1920s, Jack had been associated with the Barnum and Bailey, and Sells Floto circuses, and had gained considerable experience in the business. By the mid-1920s, this form of entertainment had lost almost all of its public appeal and it seemed certain that the curtain was about to fall on the entire industry.

Still, the Miller Brothers 101 Wild West Show didn’t want to surrender without one last try. Captain Jack’s knowledge of the trade qualified him to superintend the 101’s attempt to revitalize their show, and his name still carried no small weight. “He was one of the best known and liked men in show business,” the Lynn Massachusetts newspaper declared. Jack was hired as the 101’s “24 Hour Man” (thoroughly dependable) in January of 1927. The 101 and Captain Jack did what they could, but the Wild West show, once such an attraction, folded mid-year, signaling the end of an era.

Captain Jack’s plague of bad luck didn’t get any better and his health gradually declined. Ultimately in 1927, he was placed as a patient at the Fergus Falls, Minnesota State Hospital, where he spent the last seven years of his life. After his death in April of 1934, at 74 years of age, he was buried at the cemetery on the institution’s grounds.

Toned almost as if there was a successful career in its premature death throes, this melancholy summary closing Captain Jacks missive in a 1911 Outdoor Life may have foreshadowed fateful news to come: “I shot with every rifle expert, traveled from ocean to ocean and was never beaten. I even challenged Doc Carver to shoot for the title”.