Dissecting A .44-77

feature By: Mike Nesbitt | August, 22

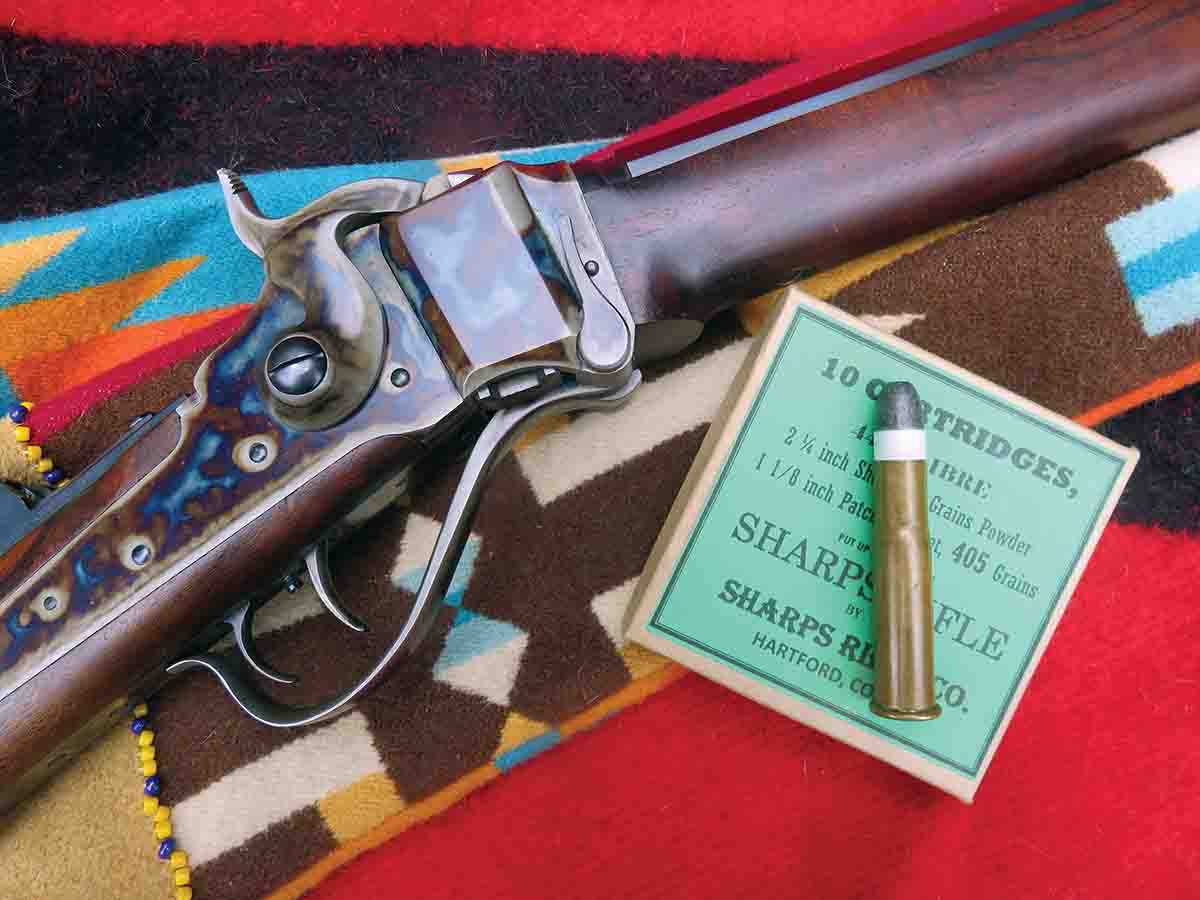

While at a cartridge show, Jerry Mayo showed me a cartridge he could not identify. It was an old paper-patched load with the paper torn off the exposed part of the bullet. I looked at it for a couple of seconds and decided that I knew what it was. However, before sounding off on such knowledge, I asked the man at that table for a price. He admitted that he couldn’t identify the cartridge and suggested that I could have it for two dollars. That was an immediate sale and I explained to him how I would replace the torn patch and make it a collectable cartridge again.

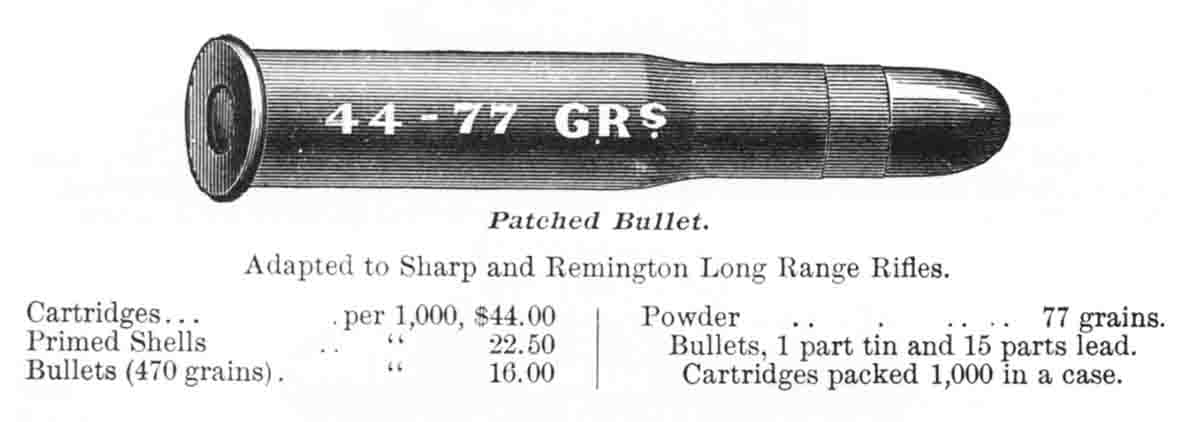

On the trip heading back home, I got the bright idea about taking the whole cartridge apart to check on the bullet’s diameter and weight, plus the weight of the powder charge. The .44-77 had various loadings back in its heyday and there was no way to tell which one this was just by looking at the outside. A few things could be determined from the outside, of course, such as the Berdan priming and the lack of a headstamp on the raised head of the case. So, a quick plan for dissection was made.

Overall, the loaded cartridge measured just under 3 inches long. I will get more technical for measurements of the bullet, but for the entire cartridge, 3 inches is plenty close enough. The paper-patched bullet was pulled, using an inertia bullet puller so it was undamaged, ready to be measured before being repatched and loaded back into the case. My old balance scale told me this bullet weighed 406 grains, which was advertised as a 405-grain bullet, 11⁄8 inches long with a cupped base.

The bullet appears to be swaged, as I cannot find any casting line. It is slightly tapered, with a diameter of .435 inch where the paper would start near the nose of the bullet then it tapers back to .438 inch at the base. That measurement is noticeably larger than what is commonly recommended for a .44 Sharps paper-patch bullet. To be sure about it, I measured it again and got .434 inch and .438 inch. (Now, I have to get a mould from KAL about the same size.)

However, I can’t say the bullet wasn’t cast, perhaps with the casting line rubbed off from the almost 150 years of age. The fact that the bullet does have a flat point, along with the cupped base, tells that it could have been cast in a nose-pour mold. For now, however, I’ll stay with the guess that the bullet was swaged even though the flat point does look like it might have had a sprue. Perhaps that’s my imagination.

Underneath that bullet was a hardened lube disc which was a full 1⁄8-inch thick. The lube, from what I could see of it, was beeswax or a beeswax mix. The fact that there was no card wad between the lube and the base of the bullet supports my theory about not using a card over the lube if the bullet has a cupped or hollow base. I think that one would want the lube, which becomes a liquid under pressure, to fill the cup or hollow base and add its hydraulics to expand the base of the bullet.

The lube disc was actually stuck to the base of the bullet and it came out of the case when the bullet was pulled. The lube needed to be “broken away” from the bullet to separate them but it did break cleanly and came off all at once.

We can speculate that using a card wad over the lube and under a cup base bullet does no harm. But in my “guesstimating,” it doesn’t do any good either because the card wad would still be forced into the cup of the bullet, which would pull the edges of the wad away from the bore, so the card wad would not do its intended duty. Guessing could continue, of course, but my only assumption here is that this was an old factory load and it did not contain a wad over the lube.

The original paper measured almost .002 inch in thickness and the paper from Buffalo Arms, which I’d use to repatch the bullet is about the same thickness. Even before digging the powder out of the cartridge case, the bullet was repatched with two wraps so it would be dry and ready when the old cartridge was to be reassembled.

Pulling the over-powder card wad was easier than what I had expected. The wad was pierced with a leather awl and then it was tipped out quite freely. That card wad was measured and it was .030-inch thick, looking almost identical to the card wads that I punch out of table-backing today. One sign of age was some white mold, which was also on the lube disc.

The powder flowed out very nicely and that surprised me too. What I had expected was compressed powder that would need to be broken loose before it would pour out of the case. Not so at all. All of the powder poured out of the case with the exception of some small individual granules, perhaps a dozen, that adhered to the brass and I didn’t feel it necessary to scrape them off for their tiny weight.

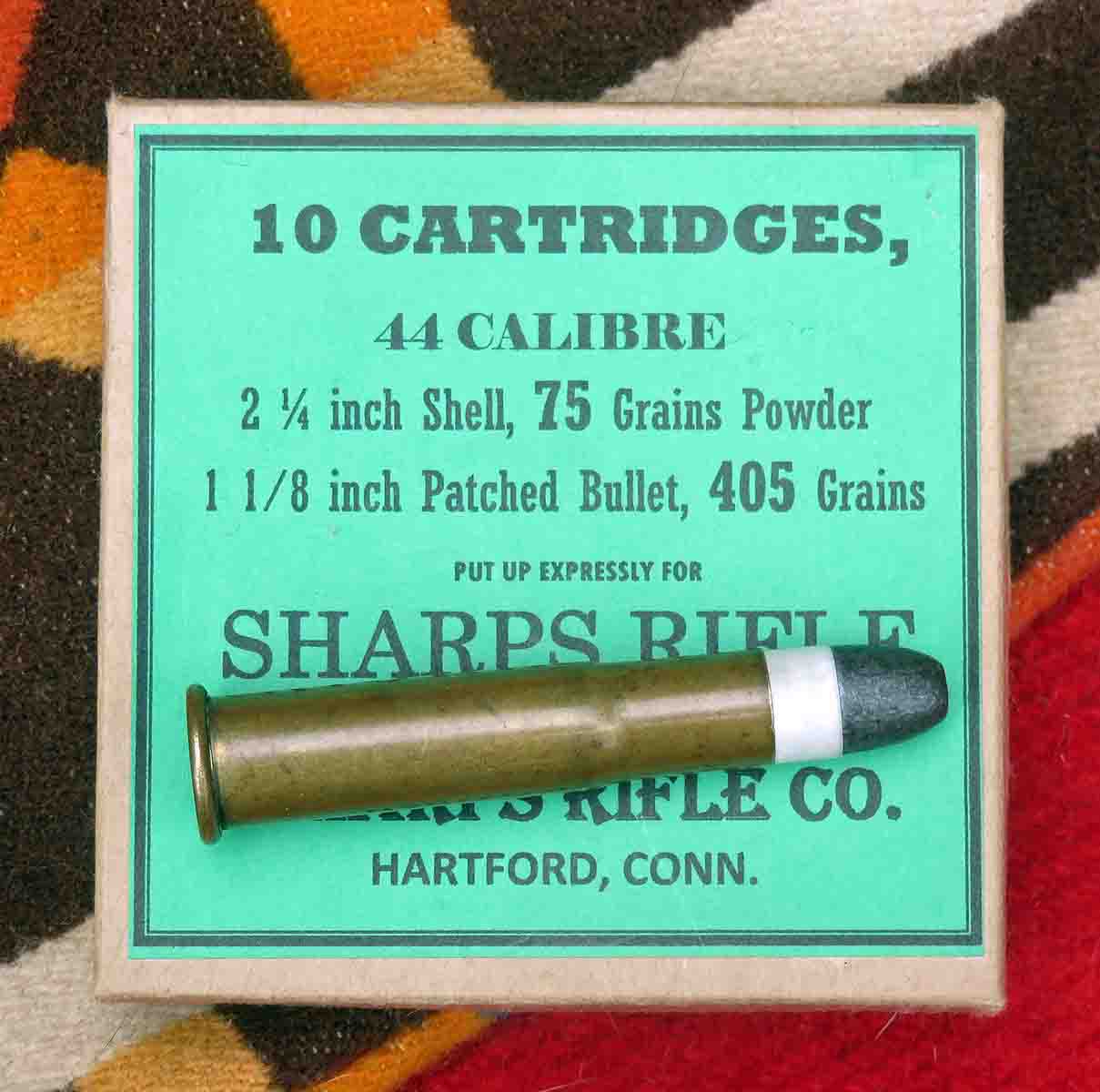

The powder was weighed and I shouldn’t have been surprised that it weighed 77 grains. Actually, it weighed about 76.9 grains but I’ll give it that extra tenth of a grain for the tiny amount of powder, which remained inside the case. That amount of powder should identify this load as being from UMC because the same cartridge (with the 405-grain bullets) were given 75 grains of powder when loaded either for or by Sharps.

Winchester also loaded .44-77 ammunition, but I’m not sure if Winchester ammunition used Berdan primers. I’m also not sure when Winchester began loading for the .44-77. So, based on what I have gained from the history books, I’ll say this cartridge was assembled by UMC.

Actually, I can’t be totally sure that this round isn’t a handload, or a reload. But I don’t think it is because there is no evidence of it being fired or tooled in any way. The looks of the swaged bullet support the factory load assumption.

The powder itself looked very good – I wish I could get more of it! The granulation was rather fine and the color very dark. I compared it to 1½ Fg Swiss powder and it looked slightly finer, with smaller individual grains than the new powder. I took a photo of the old powder next to a small cup of the Swiss 1½ Fg and I wish I had some Swiss 2Fg on hand to make another comparison. For the old powder to weigh 77 grains, and yet, need no compression to be loaded does strongly suggest that it is a denser powder.

With all of that done, the powder was poured back into the case and a new .030-inch card wad was pushed down over it. I tried to gauge the depth of the card wad by the marks on the inside of the case neck, which showed the white mold color from the lube. Perhaps I seated the wad a touch too deeply because after the original lube disc was replaced and the bullet then pushed in until it stopped, the overall length of the cartridge is now slightly less than the three inches that it originally was. But I do consider my efforts as success, the cartridge looks like it should again with the full paper patch on the bullet.

Now I have what I think is a fine example of an original .44-77-405 cartridge and I really do wish I could tell you how it shoots. That probably won’t happen, even if the old primer would fire like it would when it was new. Instead of shooting it, I’ll just keep it and use as a good accoutrement in photographs. From a more practical standpoint, this cartridge and its components do give me some better footing on making new paper-patched ammunition for the .44-77. Knowing the details about this cartridge, inside and out, make it that much more of a treasure.

We can speculate that using a card wad over the lube and under a cup base bullet does no harm. But in my “guesstimating,” it doesn’t do any good either because the card wad would still be forced into the cup of the bullet, which would pull the edges of the wad away from the bore, so the card wad would not do its intended duty. Guessing could continue, of course, but my only assumption here is that this was an old factory load and it did not contain a wad over the lube.

The original paper measured almost .002 inch in thickness and the paper from Buffalo Arms, which I’d use to repatch the bullet is about the same thickness. Even before digging the powder out of the cartridge case, the bullet was repatched with two wraps so it would be dry and ready when the old cartridge was to be reassembled.

Pulling the over-powder card wad was easier than what I had expected. The wad was pierced with a leather awl and then it was tipped out quite freely. That card wad was measured and it was .030-inch thick, looking almost identical to the card wads that I punch out of table-backing today. One sign of age was some white mold, which was also on the lube disc.

The powder flowed out very nicely and that surprised me too. What I had expected was compressed powder that would need to be broken loose before it would pour out of the case. Not so at all. All of the powder poured out of the case with the exception of some small individual granules, perhaps a dozen, that adhered to the brass and I didn’t feel it necessary to scrape them off for their tiny weight.

The powder was weighed and I shouldn’t have been surprised that it weighed 77 grains. Actually, it weighed about 76.9 grains but I’ll give it that extra tenth of a grain for the tiny amount of powder, which remained inside the case. That amount of powder should identify this load as being from UMC because the same cartridge (with the 405-grain bullets) were given 75 grains of powder when loaded either for or by Sharps.

Winchester also loaded .44-77 ammunition, but I’m not sure if Winchester ammunition used Berdan primers. I’m also not sure when Winchester began loading for the .44-77. So, based on what I have gained from the history books, I’ll say this cartridge was assembled by UMC.

Actually, I can’t be totally sure that this round isn’t a handload, or a reload. But I don’t think it is because there is no evidence of it being fired or tooled in any way. The looks of the swaged bullet support the factory load assumption.

The powder itself looked very good – I wish I could get more of it! The granulation was rather fine and the color very dark. I compared it to 1½ Fg Swiss powder and it looked slightly finer, with smaller individual grains than the new powder. I took a photo of the old powder next to a small cup of the Swiss 1½ Fg and I wish I had some Swiss 2Fg on hand to make another comparison. For the old powder to weigh 77 grains, and yet, need no compression to be loaded does strongly suggest that it is a denser powder.

With all of that done, the powder was poured back into the case and a new .030-inch card wad was pushed down over it. I tried to gauge the depth of the card wad by the marks on the inside of the case neck, which showed the white mold color from the lube. Perhaps I seated the wad a touch too deeply because after the original lube disc was replaced and the bullet then pushed in until it stopped, the overall length of the cartridge is now slightly less than the three inches that it originally was. But I do consider my efforts as success, the cartridge looks like it should again with the full paper patch on the bullet.

Now I have what I think is a fine example of an original .44-77-405 cartridge and I really do wish I could tell you how it shoots. That probably won’t happen, even if the old primer would fire like it would when it was new. Instead of shooting it, I’ll just keep it and use as a good accoutrement in photographs. From a more practical standpoint, this cartridge and its components do give me some better footing on making new paper-patched ammunition for the .44-77. Knowing the details about this cartridge, inside and out, make it that much more of a treasure.

Excerpts from the Sharps Rifle Company price list, January, 1878

To Reload Shells for Sporting Rifles

It is unnecessary to weigh the powder for these cartridges. If the shells be enlarged so that the bullet fits loosely, they should be reduced with the shell reducer, which can be procured at the armory or any of the agents of the Company.

Charge with the desired quantity of powder, placing a pasteboard wad upon the powder, and force it down the full length of the follower. Insert upon the wad a lubricant disk composed of one-part pure beeswax to two parts sperm oil in weight, to occupy three-sixteenths of an in in length in the shell.

Dip the base of naked bullets up to the forward ring in melted lubricating compound, taking care to fill the grooves.

Place the bullet in the chamber of the bullet seater, introduce the shell, and press it home with the hand.

Wipe the cartridge clean, and it is ready for use.

In casting bullets, heat the moulds nearly as hot as the molten lead, having first cleaned them of all oil.

The bullets comprised in the above list are made with the greatest care, the lead being alloyed to a proper degree to insure accuracy and prevent leading the rifle barrel. The patched bullets are swaged under powerful presses, which secures the greatest uniformity in density. The patches are cut from bank note paper of even thickness, manufactured for this Company expressly for the purpose, and are put on with the utmost exactness. The special long-range bullet composed of an alloy known only to and exclusively manufactured by this Company, is giving very fine results.

…Our estimate of quantity of powder is based on the best “F.G.” brands in general use. A stronger powder can be used in our rifles with perfect safety, but is liable to be destructive to cartridge shells, and, we think, gives no better results. Expert riflemen, however, differ so greatly on this point, that we prefer to leave our customers to decide it from personal experience. We have found the powder of the Laflin & Rand Co. and the Oriental Powder Co all that could be desired.

From Sharps Rifle: The Gun That Shaped American Destiny by Martin Rywell, Pioneer Press, Union City, TN.