The Wyoming Schuetzen Union’s “Center Shot”

The Cable Matches

column By: Jim Foral | August, 22

The Amateur Rifle Club of metropolitan New York considered themselves up to Ireland’s challenge, and in front of a considerable throng of spectators, went on to prove decisively that they were, in their great Creedmoor victory that year of 1874.

To one extent or another, the submerged cable connected North America to Europe since about 1860. It was, for the great bulk of Europeans and Americans, a less than beneficial system, but it was a way for distant continents to communicate. The world made do with it before Guglielmo Marconi wirelessly accomplished the same objective about 1902. It took some time for Marconi’s system to be adopted and supplement the cable.

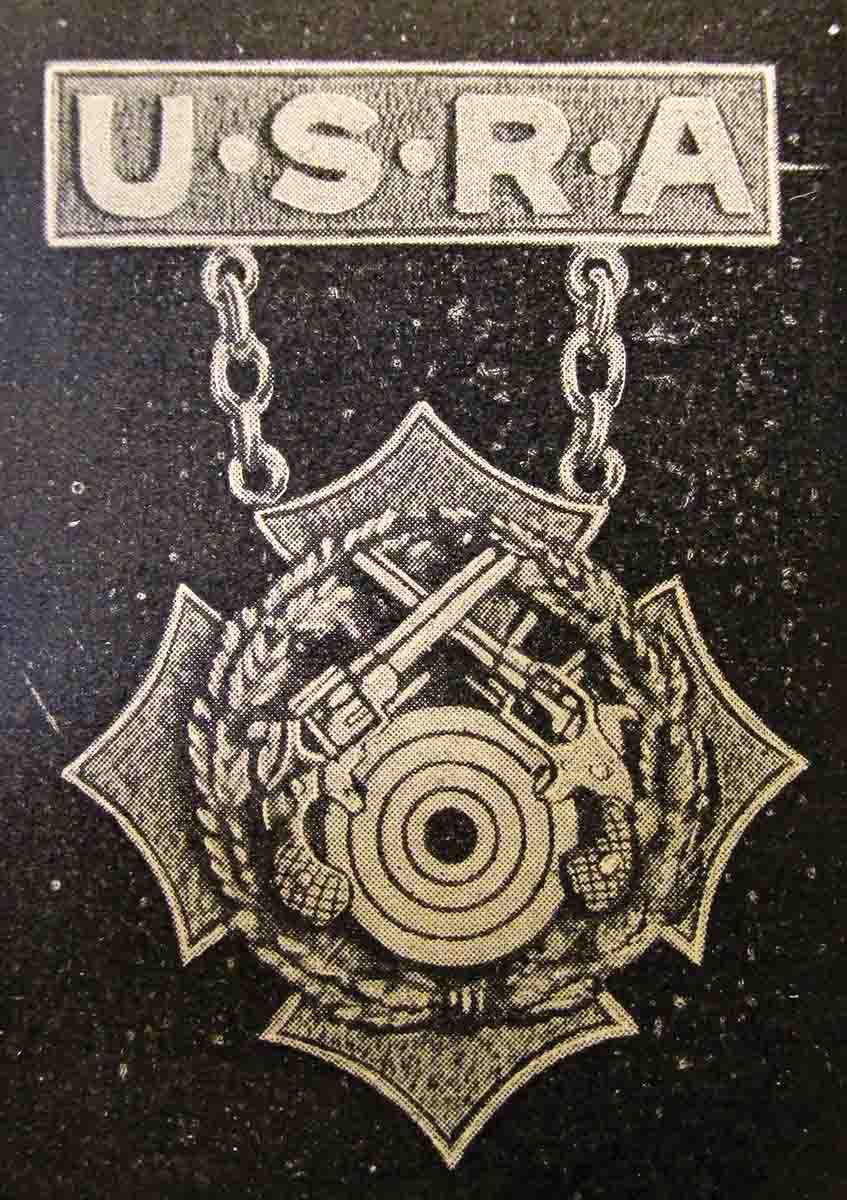

The U.S. Revolver Association was formed to respond to the Frenchmen’s proposition. Agitating for taking up the gauntlet was E.E. Patridge of Boston (of Patridge sight fame) and Abraham Lincoln Artman Himmelwright (namesake of the president who was assassinated in the year of his birth) of New York City. On April 17, the officers of the newly-formed club met at Conlin’s gallery on 6th Avenue in New York City. At that point, the French were dragging their feet in providing details, but in time particulars were finalized.

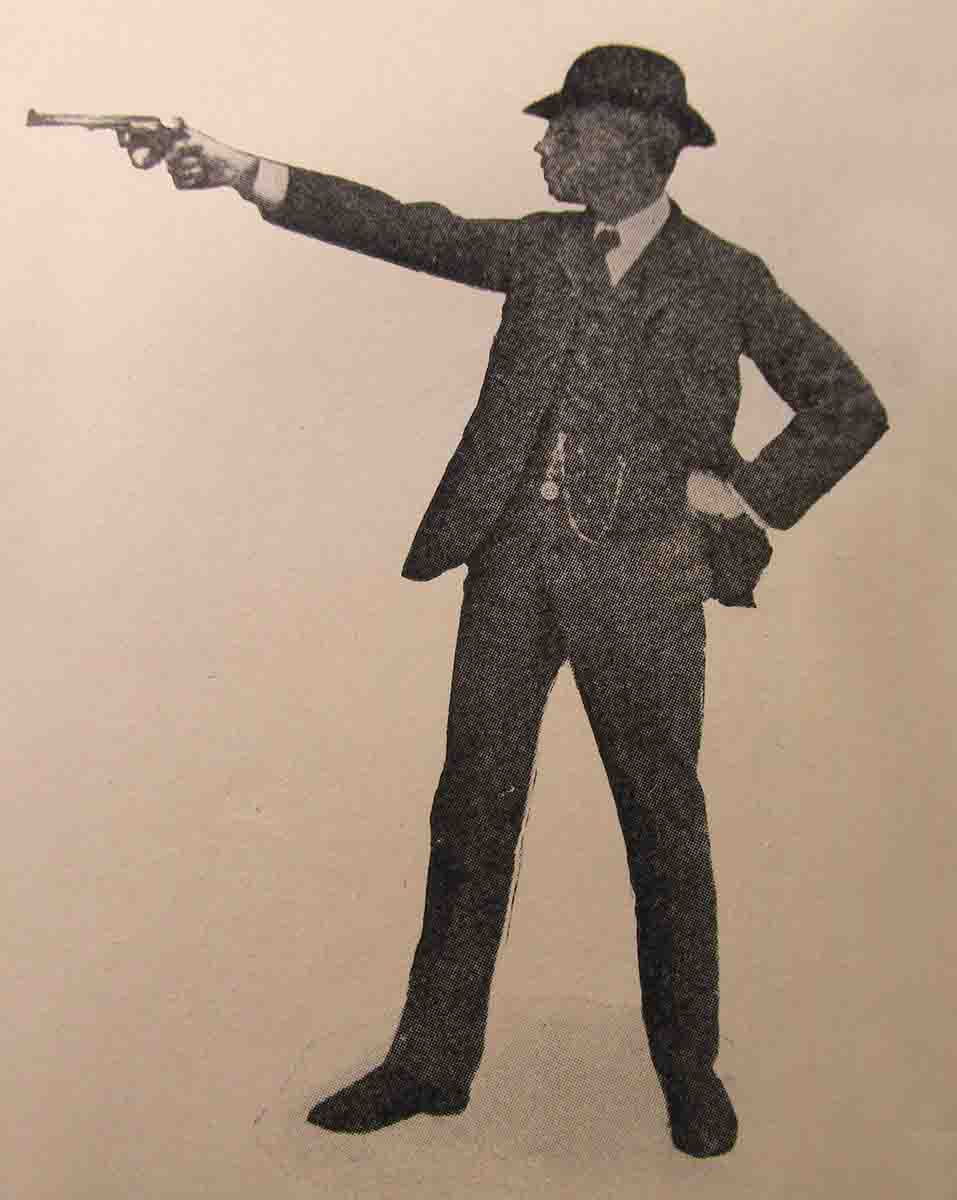

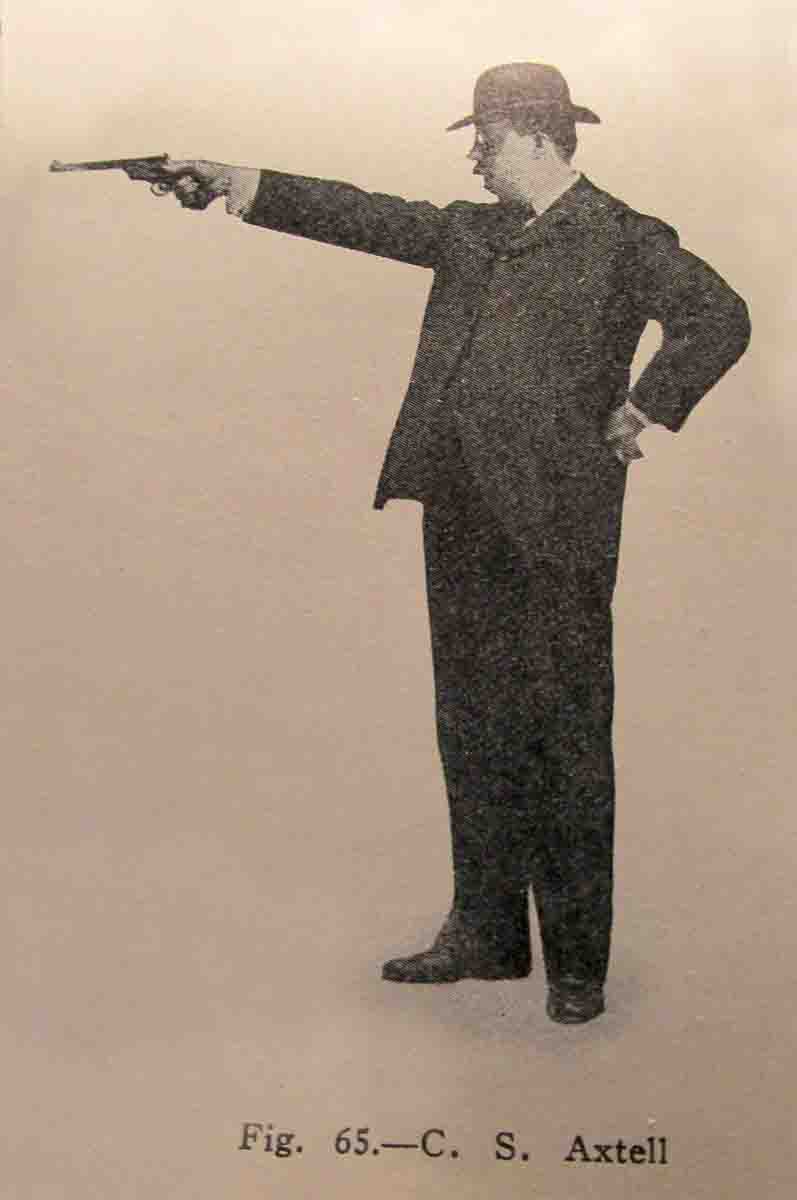

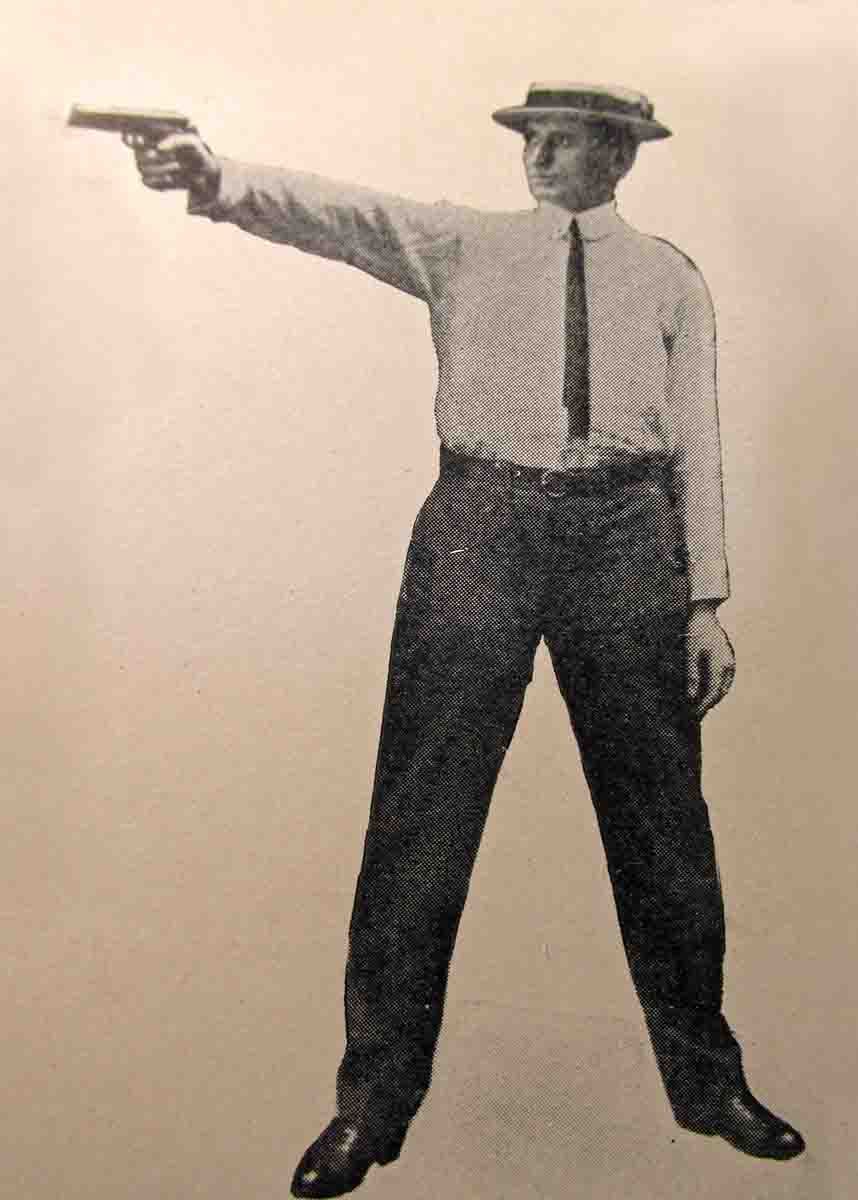

Each team was to be comprised of 10 men. Each competitor was to fire, from standing, 30 shots on the Standard American Target at 50 yards and 30 shots at the target selected by the French team at 16 meters (52.5 feet). Each target was a 300-point possible for a 600-point aggregate. Each team had shipped a supply of their targets to the opposition. All shooting was to be done offhand and refereed by two neutral gentlemen.

The American end of what was billed as the “Franco-American Cable Match” was shot at Armbruster’s Park in Greenville, New Jersey on June 16, 1900. At the same time, the Frenchmen were to be facing their targets at the range of Castine Renette in Paris. The American targets arrived in Paris late, and this delayed the French leg of the match.

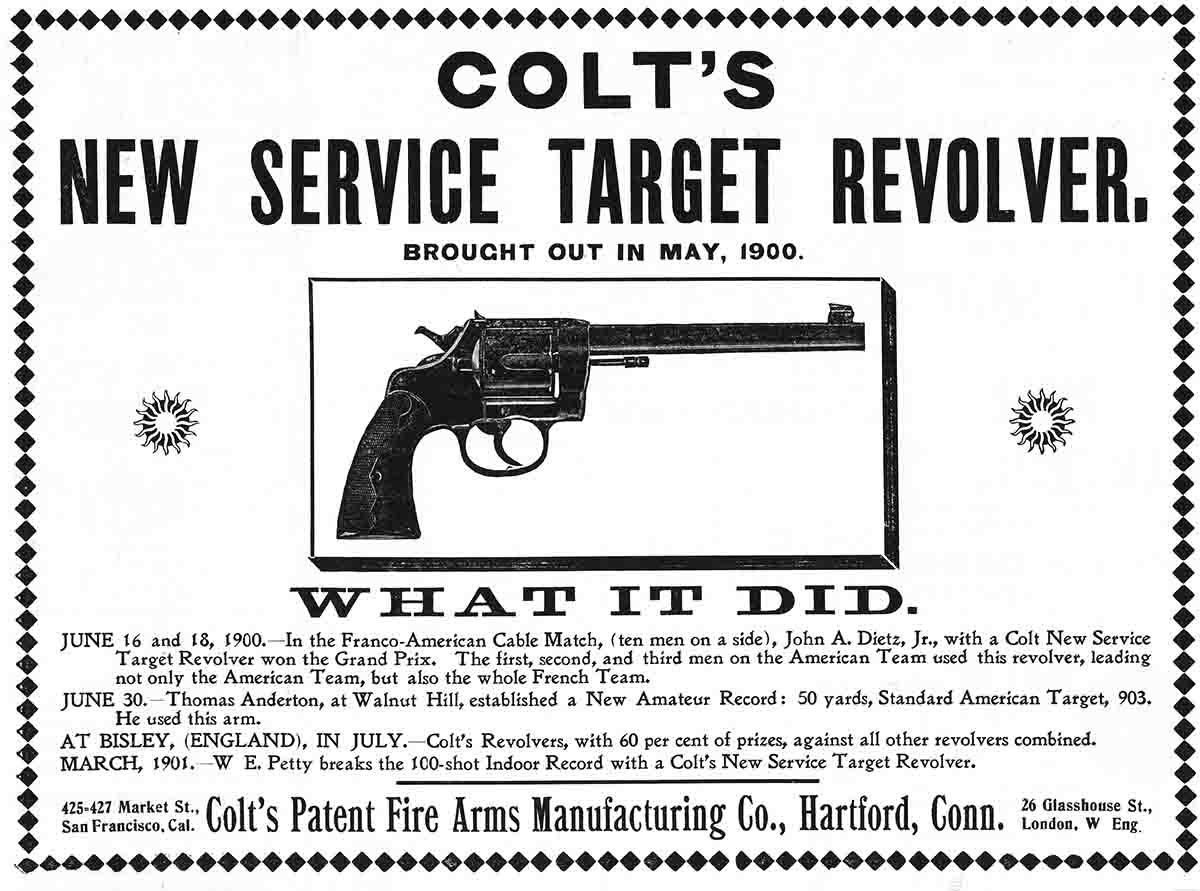

The French got to their range a few days later. When the dots and dashes transmitted from Paris and received in the U.S. were deciphered, it was made known that the American team’s score was 61 points better than the French side. Immediately, Colt’s Patent Firearms Manufacturing Company seized the timely opportunity to gloat in the June 30, 1900, advertising section of Forest and Stream: “Four of the men on the American team used the Colt New Service (target) revolvers. They stood 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 4th on the French target, and one position off on the aggregate.” Colt’s competition invested in ad space as soon as the match was announced in late April, but succeeded only in looking foolish when they proclaimed prematurely: “Most of the competitors will probably use Smith and Wesson revolvers.”

The results of the 1900 match did not satisfy the French marksmanship officials, who soon afterwards demanded to be pleased. A rematch would be the best way to accomplish this. What they had fielded in 1900 was the best talent that could be found in Paris alone, and another team, this time put together from the whole of France, would be a stronger unit and a more comprehensive representation of their country. To this end, in June 1912, the French appealed to the USRA for another match to be held in June of the following year. The Parisians in charge got busy and canvassed what talent the French Army and Navy might have and scoured the outlying shooting clubs.

Prospective American team members contested for their spots at the Walnut Hill range near Boston, where they devoted three days to tryouts and team selection. Four of those making the cut (J. Dietze, Reginald Sayre, B.F. Wilder and J.B. Crabtree) were familiar faces that had served on the 1900 team. Several of the other 11 members had nationally recognizable names.

It was agreed that both sides would shoot their scores on June 30, 1903, and the Americans did so. Again, the targets didn’t arrive in Paris in time, and the Frenchmen, recruited from seven localities besides Paris, fired a few days later. In the end, only the bottom line mattered. The U.S. Revolver team scored 7,889 points, a significant 249 points ahead of the French, who posted 7,640.

The United States Revolver Association was not a “flash in the pan.” For many years after its 1900 formation, it remained a force to promote revolver shooting in the U.S. and acted as the sport’s governing body. It also standardized a uniform set of rules. In 1906, the USRA held its own telegraph matches to augment the National Matches. It did the team selection for the 1908 Olympic shooting team and raised the funds to send it to London that year. Over the years, the USRA trained Olympic pistol teams. It held national as well as local handgun matches, and ran everything for the U.S. Olympic pistol teams through 1936. They handed out medals galore and were still conducting postal matches when they were disbanded about 1980.

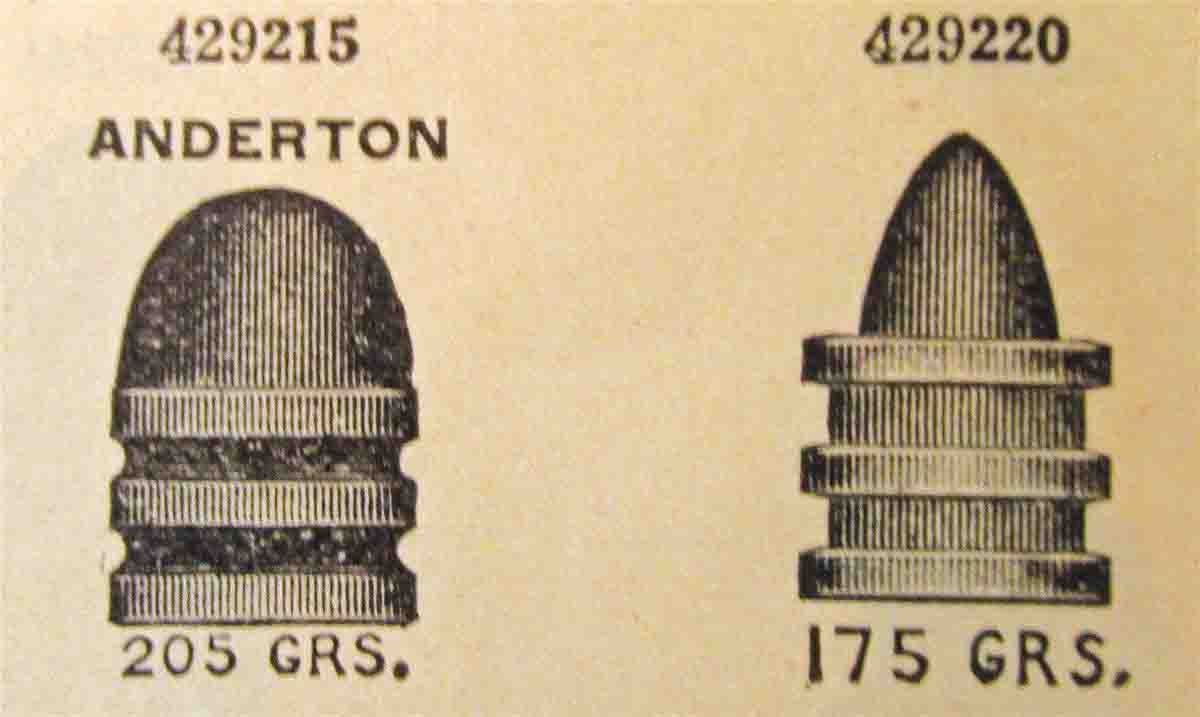

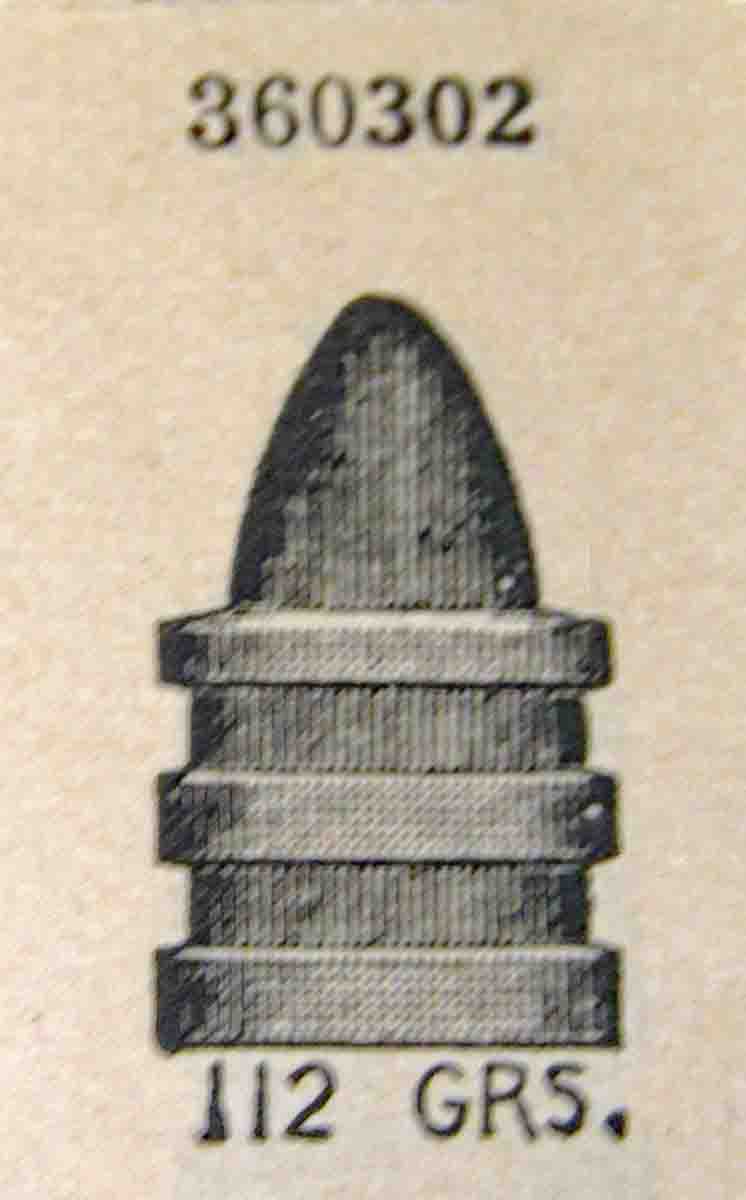

When Thomas Anderton of Boston made a world’s record revolver record in 1901, he did it with his own .44-caliber bullet design. Doubtlessly, the mould was fashioned by Ideal Manufacturing. Barlow promoted the bullet and the shooter by making Anderton’s 200-grain (#429215) bullet a catalog item before 1903. Barlow did the same thing with the A.L.A. Himmelwright 175-grain .44 wadcutter with its odd frontal projection, assigning it number 429220, and made it famous in its generation. Two other USRA standouts got the same Barlow treatment before their momentary celebrity died out. Original Cable Team member B.F. Wilder of New York City dreamed up the .38 Special bullet (#360271), which featured a broad base band and weighed 150 grains. Its square shoulder cut a clean hole, making for certain scoring. Wilder’s teammate, J.B. Crabtree of Springfield, Massachusetts, thought his 115-grain, square-shouldered bullet to be a lead-saving, recoil-reducing advantage. In rapid fire matches, Crabtree’s bullet (#360345) made good sense.

The Manhattan club had some big-name talent. Walter Hudson and W.H. French were two of the best offhand shots on the East Coast, while B.F. Wilder, A.L.A. Himmelwright, and Reginald Sayer were tops with the revolver and had proven to be no slouches with the offhand match rifle. Their hopes were as high as their confidence. Still, the Caribiniers carried away the victory in the first cable meeting of the clubs. Some would venture to call the scores, 20,850 to 20,417, close. Anyone calling the French victory a fluke, would not say that a second time.

The formal request for a 1906 match was sent to the Paris marksmen in December 1905. Accompanying the proposition was the Manhattan Rifle and Pistol Association’s material gesture of goodwill and international friendship, an engraved silver souvenir cup 20 inches tall. The Carabiniers instantly responded graciously and accepted the challenge. The Frenchmen used the opportunity to suggest that the single shot pistol be allowed in the now annual cable competition.

As everyone expected, Walter Hudson posted the high aggregate for the U.S. In doing so, he broke the French and the world record on the 200-yard French target. Second place was revolver specialist J.A. Dietze of New York City, followed by Thomas Anderton, Boston’s great revolver shooter. The French team was particularly strong and would continue to be. Those representing the press who noticed this, maintained that it was “better balanced.” Then, too, the team had been drawn from a larger and wider pool of candidates. After progressively narrowing the considerable gap in score in the course of the cable series, the Manhattan Rifle and Revolver Association at last outpointed the Parisian crack shots with their first win at the 1907 event.

On May 23, 1908, Harry Pope joined in the combined rifle shooting effort of Hudson and French to help the American squad rack up an aggregate of 21,125 points. Such a score would have won the match at almost any year of the match’s run. The French had yet to shoot. The Forest and Stream writer promised that his paper “will report scores from Paris later.” Mysteriously, the scores, or any mention of the Carabiniers the rest of the year, were never printed.

Hudson and French were one and two again at the June 1909 American team shoot at Armbruster Park. Harry Pope was again on the team, and J.T. Humphrey was also a firing member. The U.S. was able to beat the Europeans handily in the revolver segment, but despite having a seemingly solid rifle squad, the Manhattan riflemen were simply outclassed by the French. In the end, it was the Carabiniers with 21,246 and the New Yorkers 20,990.

The novelty of engaging in an international pistol/rifle match with hardly leaving the county was an early twentieth-century notion. All fads eventually run their natural course, and the heyday of the Cable Match had played out its concluding scenes.