Norman S. Brockway

Gunsmith & Rifleman

feature By: Steve Garbe / Harold “Polecat” Porter / Mark Barnhill | August, 22

This information was taken from the archives of the late rifleman Harold “Polecat” Porter and was sent to us by Mark Barnhill, well-known slug rifle enthusiast and competitor. Mark has been responsible for keeping alive much of our tradition of precision shooting with the uniquely American, heavy benchrest muzzleloading slug rifle. Whether one knows it or not, these were the firearms that set the standard for ultimate accuracy before and after the advent of the cartridge breechloader. Men such as Norman Brockway experimented throughout their life to perfect the early-day benchrest rifle and contributed greatly to our collective knowledge on truly accurate and precision shooting.

This newspaper interview, dated from 1936, details much of Brockway’s life and as such will be of great interest to the student of the rifle; especially those who appreciate the efforts of our early gunsmiths in their quest for accuracy and precision. – Steve Garbe

Ninety-Four Years Fail to Dull Interest Of Veteran Rifle Maker

Ninety-Four Years Fail to Dull Interest Of Veteran Rifle Maker

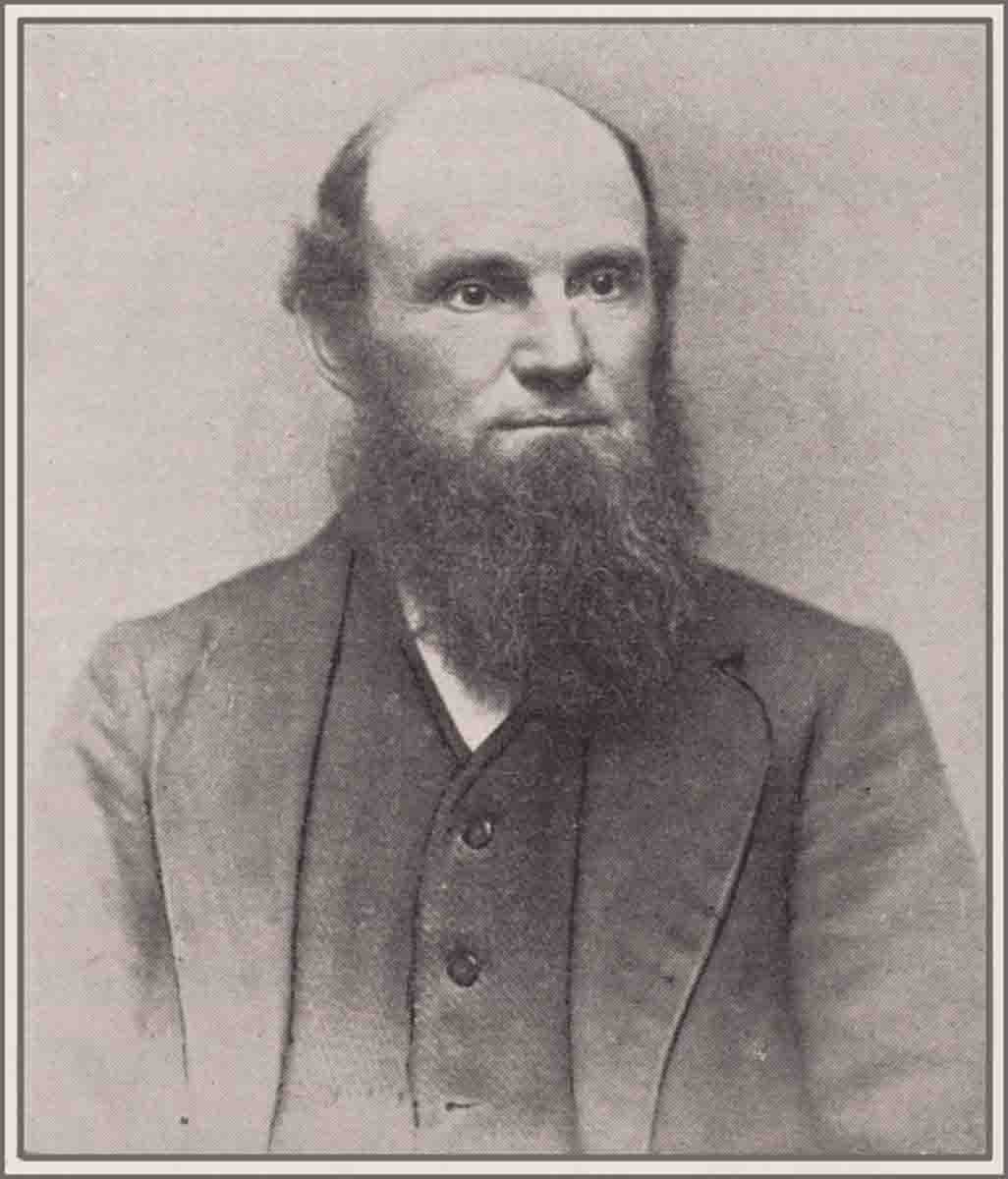

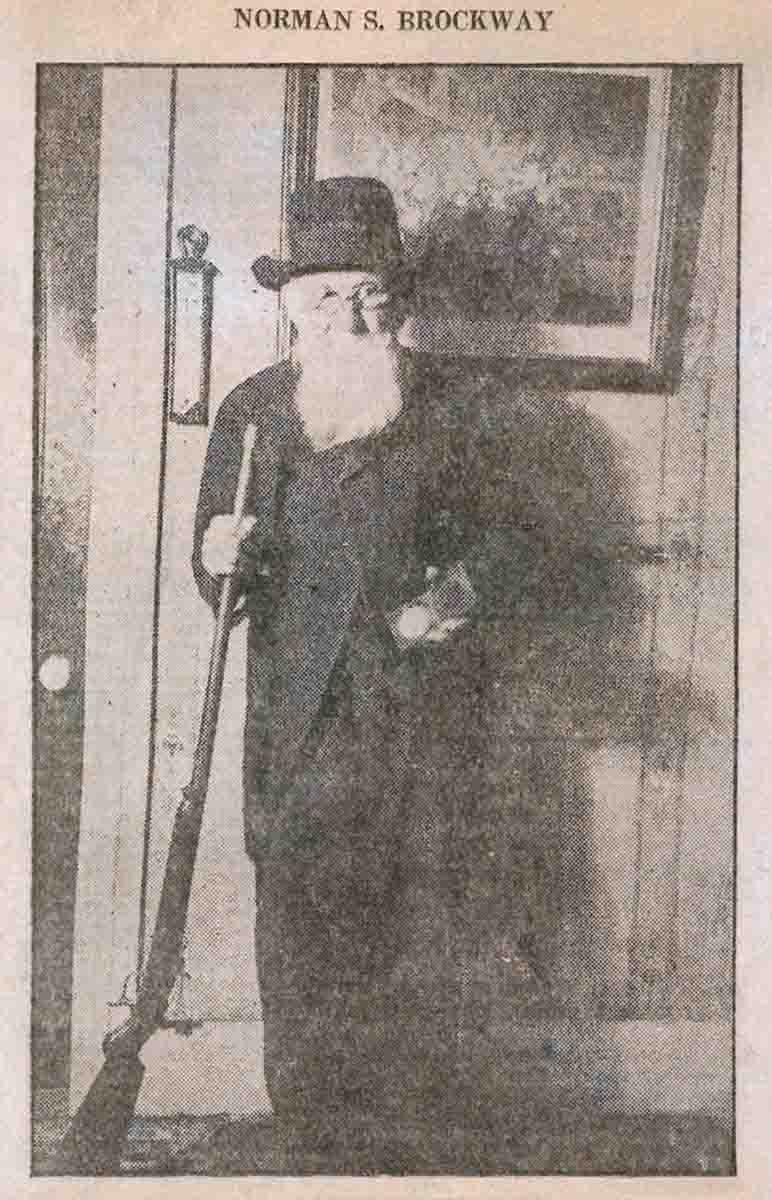

Ninety-four-year-old Norman S. Brockway, one-time famous maker of precision muzzle loading rifles, leaned forward, arms resting on the sides of an old-fashioned rocker at his home in West Brookfield. His bushy grey beard trailed white against the black frock coat, as he softly talked his eyes were focused far beyond the walls of the room as if he were back there in 1862, during the Civil War, filing gun sights at the Springfield Armory.

(The Muzzleloaders Versus Breechloaders match photo taken at Vernon, Vermont on May 26-27, 1886, included attendees [front row left to right]: Norman S. Brockway seated in the front row, second from left; Hiram W. Smith is to the left of Brockway with David H. Cox, D.A. Brown and B. Stephenson to the right. Also in attendance [back row left to right]: C.W Hinman, D. Park, R.C. Cressy, J.N. Frye, Frank I. Fenn, C.F. Fletcher, William V. Lowe, William Maynard, F.J. Rabbeth, W. Milton Farrow, Milton F. Roberts, George Ellsworth.)

"They weren’t poor in those days. The Government had gold to pay us with. I remember the zinc covering at the paymaster’s desk. It was worn hollow from the heavy gold coins. And when we got our first paper money…” A chuckle escaped from his lips.

“The fellows took the money outside and spread it on the sidewalk and looked at it. Everybody laughed. It was a good joke.”

A Rugged Individualist

Of recent times we have heard much of “the rugged individualist”. Well, he’s an excellent example. Born away back in 1841 at Charleston, New Hampshire, it was after three short years that his family moved him across the Connecticut river to live in Bellows Falls, Vermont. Like many youths of that time, he never completed grammar school. But in that era, and especially with that kind of man, a cut and dried book education was not essential.

He grew up in Bellows Falls learning the carpenter’s trade, but it was his love of machines and fine workmanship that changed his life and made a definite personality of him. When he was only 13 he worked nailing lathes to house frames, but for one of his inquiring and experimental nature, this task was too monotonous. So he gave that up and found for himself a place in a small machine shop where he was paid the salary of 92 cents a day.

However, word came up-river that at the United States Armory men were receiving as high as $7 a day, so he packed his tools and came down the river to Springfield. He applied for a job and they placed him on the payroll at $2.40 a day for which he found himself at work on the main springs which were used to snap the gun hammers down. In time he filed gun sights, a painstaking job requiring the utmost care and accuracy, for if one were to spoil many sights his pay envelope would be very slim when he received it. Brockway well remembers this work.

“The machines they got now,” he commented with the amusing disdain of an old man for the new generation and its products, “you can watch the machines work. But a file won’t go by itself. You’ve got to push it. And it’s hard work.”

At the Armory he remained until February of 1864, when he traveled southward to the Norwich Arms company at Norwich, Connecticut, where his father also worked. But as yet the youngster Brockway had not yet struck out for himself. His ideas were forming in fragmentary visions of his own independent shop which he thought of more and more. He had not yet made definite plans, so in ’65 he returned to Springfield to work at the Smith and Wesson “pistol shop” as he calls it, where for a year he turned out revolver cylinders.

Shop Owner

But the spring of ’66 found him back in Bellows Falls with his father where together they dug out a foundation and built on this a new house and shop; and by ’67 he was the proud owner of a two story building 10 yards long and almost as wide which for many years to come served as his place of business.

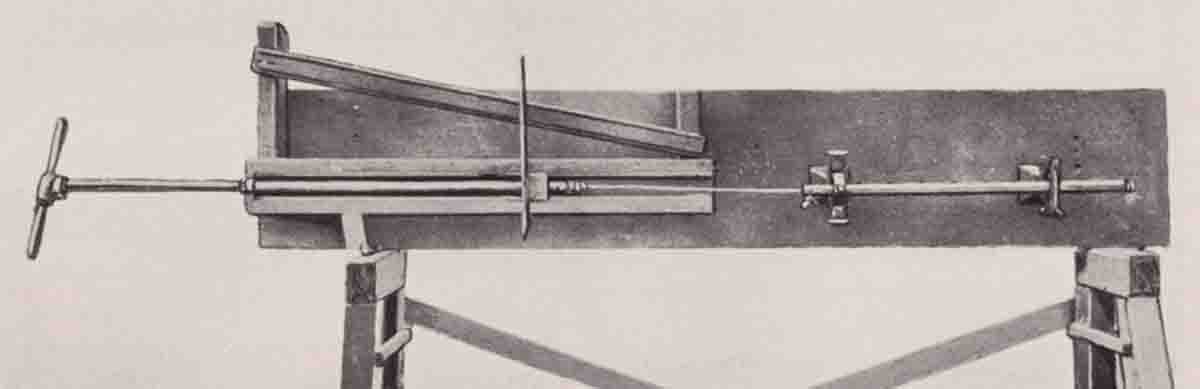

From Worchester the young Brockway bought an engine lathe, and with the help of this he made all the rest of his tools, a milling machine, a drill press, and a rifling machine. With this collection of his own handiwork he drilled rifle barrels, reamed them, and put inside them the grooves or ridges which spin the bullet as it travels through the barrel.

At that time there was no electric power available, so to turn the wheels of his machinery he designed an ingenious steam engine which eliminated an important push rod. His shop was a great meeting place for almost all of Bellows Falls, and among the people who came there were several locomotive engineers. When he first outlined the plans of his proposed steam engine, they shook their heads and tried to discourage him from any attempt.

But his self-confidence was well founded, and when he tightened the last nut and connected the mechanism to a steam pipe from the boiler which he bought, the piston moved, slowly, then faster until it was a scintillating whirr of motion. It was the matter of but short time until he belted the steam engine to the other machinery, which the steam engine drove for many unfailing years.

At South Vernon, Vermont, the National Rifle Club met annually. Of this organization Brockway was the secretary for 20 years. For these yearly matches he used his own private rifles weighing upwards of 23 pounds. “A heavy gun? Well, I’ll say.” But these rifles were fired with the barrel lying across a bench rest, and it was from these heavy precision arms that he gained his wide reputation.

Some Lenses Still Exist

For sights on his rifles he used telescopes. He knew nothing about that art, but he bought some glass, got hold of the directions for grinding and polishing the glass into the desired curvature. After a few preliminary tries he bent his effort to the task and turned out lenses which were like everything thing else he did, approaching excellence. There are still in existence many unset lenses which he ground.

Brockway’s shop was a popular meeting place for all the town band. When the boys all got together there was a great mutter and chatter of voices, scraping of chairs and loud blast of music which made up in enthusiasm what it lacked in polish. Brockway played no instrument but energetic strains of music were enough to move him to try his hand at making a violin. He looked over some wood, picked out the choicest pieces and after careful surveys of completed instruments he began cutting and shaving and planning. When he had applied the last touch he strung it up. It sounded very good, and today it has an excellent tone. On this he learned to play “Yankee Doodle” well; but he was primarily a precision rifleman, so he never took the time to learn an extensive repertoire.

His genuine interest in rifles soon took him back to his work with renewed intensity. It was literally impossible for him not to develop ideas of his own and on his personal offhand gun with which he is photographed, a development of his is prominent.

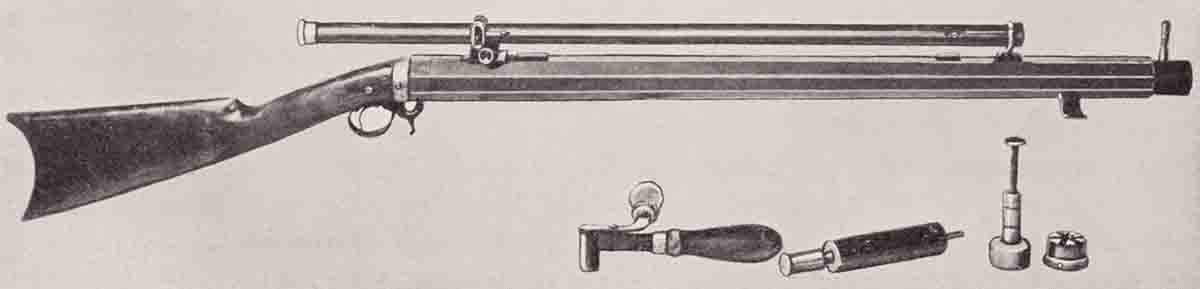

To insure accuracy in shooting these muzzle loading firearms, a false muzzle is used. This device is a piece of rifle barrel drilled and rifled exactly the same as the rifle on which it fits. This false muzzle is held in place on the true muzzle by two long metallic pins which fit into holes in the end of the rifle barrel and serve to return the false muzzle to exactly the same position every time it is used.

The powder and lead are loaded from the muzzle, and the slug is first forced through the false muzzle and then down the barrel. For firing the charge, the muzzle is removed.

Observation

It happened that one day Brockway was at another rifle maker’s shop, watching the latter repair a barrel. The workman drew off the false muzzle, but he accidently dropped it, striking the inside of the barrel with one of the long metal pins. With interest, Brockway noted this, and knowing whose gun it was he watched the results.

When after trying the rifle out its owner claimed that the aim was off, Brockway sat down and doped out a scheme whereby the false muzzle fitted on with a small key such as is used on automobile axles, and it was on his own offhand gun that he made practical application of the idea.

In modern rifles, bullets come in direct metal-to-metal contact with barrel, but with the old muzzle loaders the lead slugs used a cloth or paper patch to cover the pellet. This patch is oiled or greased for lubrication, and in the cloth variety is usually a round, accurately cut piece. When the bullet is rammed down on top of the powder, the patch is pushed in the barrel with the slug and wrapped around it.

But to Brockway the cloth patch was not satisfactory. If you put a small piece of cloth over the end of your finger and draw it down tightly, you will see that there are several folds in it. To offset this defect, Brockway milled a small device in which two or three strips of oiled paper were inserted to cross each other at the angle which would best insure a tight fit. Then, when the slug was pushed down on top of the strips, they folded about it in a neat seal.

The old rifle maker is a “man of the old school” and to him shooting while lying prone and with elaborate padding equipment is the sure sign of a weakling. When questioned about this he declared with a vehemence surprising for him, “If a man can’t stand on his own two feet, well… ” He didn’t finish the sentence, but one could see he was visualizing those days when he was active and when long range firing was the only occasion for prone shooting.

Bulls Eyes

He told of an occasion when he once shot an 800-yard range at Brattleboro, Vermont. From the firing line to the target was almost half a mile, so he took a sighting shot lying prone. He was disgusted with the results, so he quickly rose to his feet and shooting offhand he cut four holes in the bulls eye and another within an inch of the black ring. But shooting at that distance took extra powder and after the six shots he had no more. No one used his special brand, so he failed to finish the match.

During one of the annual meets of the National Rifle Club at South Vernon he shot against Pope, a rifle maker still living and world famous for his precision arms which are, however, of a breech and muzzle loading variety in which the powder is loaded at the breech and the slug from the muzzle.

The day of that particular meet was, according to Brockwy’s records, “the roughest day ever shot on the grounds.”

“The wind was so strong it blew the tent down,” Brockway explained. “Cost us $50 to fix it,” he added, small wrinkles tracing his features as he grinned at the memory of the event.

“ I had to sight three targets to the left to hit my own.”

In other words, the gale was so strong, that in 200 and 20 yards the bullet was blown almost 3 feet off its course. He and Pope were the only two men who finished the match and on this occasion Brockway won. Evidently neither “hell or high water” kept those boys from the range.

When asked about Pope, Brockway said: “Pope? Yes. He’s a pretty good fellow. He made some guns around Hartford.”

Brockway was himself well-known as a manufacturer of target rifles, and by 1896 was doing an excellent business at his Bellows Falls workshop. But fate intervened, effectively halting his productiveness.

He bought some property on Lake Sunapee, New Hampshire. Often in his spare time he went there and put in many hours of work on a house he was building. The walls were erected, the roof on, and one day he was putting the finishing touches on the ridgepole when suddenly his foot slipped. His hands flew out, grasping and tearing shingles as he slid, but they failed to halt him and he plunged over the edge.

Beneath was a rubbish pile which, had he landed right, might have broke the fall. But he struck his back just above the hips on the top of the pile and the force of the fall snapped his back like a bow pulled the wrong way.

He was badly shaken up from his 30 foot fall and his back was so injured that he could no longer do anything but the very lightest of tasks. When he recovered so that he could move around he sold the large shop and moved back across the street into the small place which had been his first workshop years before.

In 1903 he shot his last rifle match and in the same year moved to West Brookfield, where he has lived since. The machinery moved from his shop he sold to Mr. Huntoon, who was Brockway’s helper, at his Bellows Falls workshop.

The two, Wooster and Brockway, are close friends, and the younger man often talks hours with the old rifle maker, getting pointers here and there on the older methods of workmanship that went into the manufacture of a good muzzle loader.

Together they make a contrasting pair, but each is as enthusiastic as the other about their mutually favorite subject, rifles. Over the old, slightly bent figure of Brockway, the younger man towers, but get them together and size and age disappear.

Brockway is once again back in his shop. Wooster’s problems are his problems, and the elderly man thinks things out as if he were still doing the work, explains them so. And who knows, perhaps today he gains more pleasure out of this instruction than when he himself slid the carriage back and forth, arms strong, back straight, his determined mouth fringed with close clipped black whiskers of a time now past?

Thanks again to Mark Barnhill for this interesting newspaper article on one of this country’s best old-time gunsmiths. Norman Brockway was an outstanding example of the American “Rifleman Gunsmith,” an individual capable of making from scratch an accurate rifled firearm with the proper degree of fit and finish; then taking that same firearm and shooting it with a high level of proficiency. This is a rare ability that not many can claim. Brockway was also a fierce competitor at a time when the ability to shoot accurately was held in high esteem and regularly tested in many communities. Among those who are dedicated to shooting the old “slug guns,” Brockway rifles will always set a standard for quality and accuracy that few can match.