The author overlooking the basin where the .40 caliber bullet was found.

In the parlance of the West, a “cold trail” is one that had a significant period of time elapse before any tracker attempts to follow it. This describes perfectly what Sheryll (my wife) and I ended up doing on an enjoyable summer day in the badlands north of Cody, Wyoming.

With an upcoming antelope season soon to begin, I wanted to scout out a relatively new area to hunt. As I regularly hunt with black-powder rifles, it pays to check out an area extensively. Stalking is the name of the game, especially when using round ball muzzleloaders on game such as antelope. Knowing the waterholes, approaches and escape routes is vital to successfully bagging an antelope; more so if they have been pressured by hunters with modern rifles. The antelope in this particular area were very spooky and one would not get many chances for a close shot. I wanted to find some good bushwhack spots, as well as determining which areas were being staked out by big bucks.

As Sheryll and I were walking a ridge between two coulees, glassing the terrain, a curiously shaped “pebble” caught my attention. I picked it up and immediately recognized it as a rifle bullet of approximately .40 caliber. It was a paper-patch bullet and that got me really excited. The bullet had obviously been there for many years, as the patina was a dark brown except where the dirt had protected it from the elements.

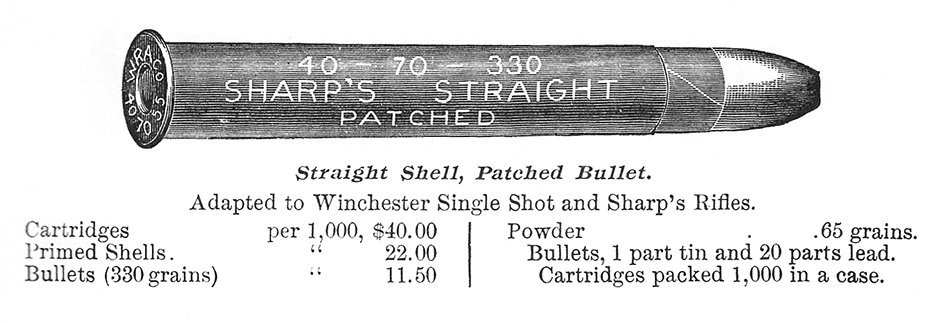

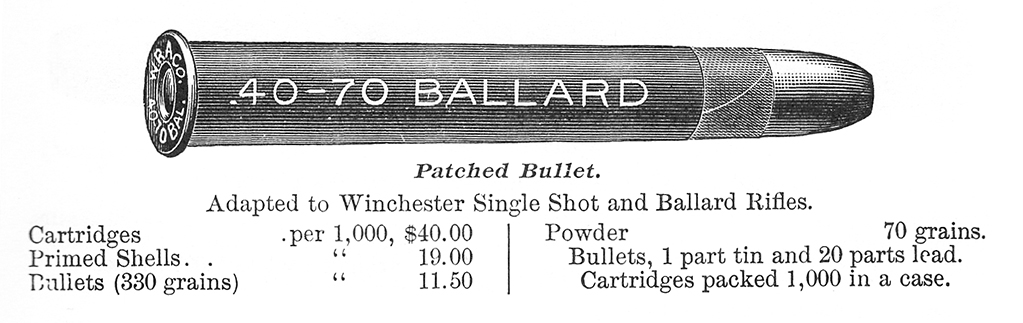

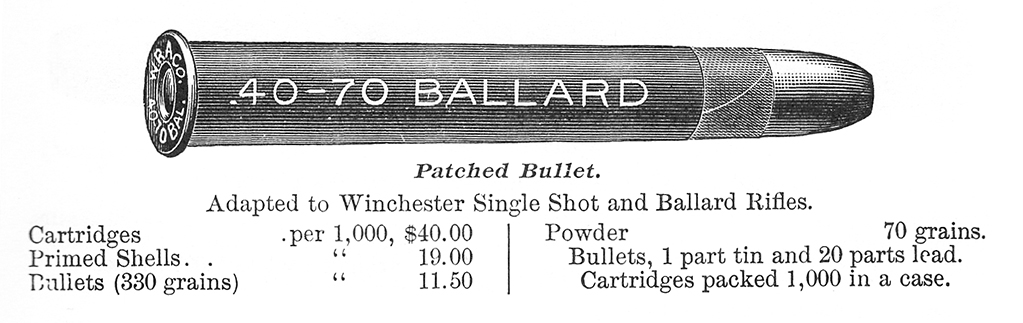

The other notable aspect about the bullet was it had not contacted a rock or the ground when it was fired. The bullet was mushroomed exactly as it would be had it contacted flesh. In fact, it did not show any deformation from hitting bone or heavy joints. When weighed on a scale at home it came in at 327.9 grains, signifying that it had weighted 330 grains when fired. This is a typical weight for paper-patched bullets in the various .40 caliber cartridges, such as 40-70 Sharps Straight or Bottleneck, 40-70 Ballard or possibly the longer 40-90 Straight or Bottleneck. However, these longer cases were most typically loaded with 370-grain bullets. The bullet had been cast, not swaged, as there was a slight void at the center of the bullet base.

In casting bullets, be careful to keep the mould hot; in this way, a very perfect ball can be produced.

But as much depends on the projectile, more especially in target shooting,

it is preferable to purchase bullets ready-made, as they are accurately swaged to the correct size.

– From the Marlin Fire Arms Co. catalog, circa 1888.

This suggested that the bullet was cast by hand and not purchased, as most paper patch bullets sold by ammunition companies of the time were swaged and many featured a hollow base. The alloy seemed to be of 1-20 tin/lead mix when I carefully tested its hardness. Again, completely in line with what was done in the 1870s. Checking an early Winchester catalog revealed that virtually all of their loaded ammunition in the heavier .40 cartridges was loaded with 1-20 alloy paper patch bullets. The mushrooming of the bullet was also typical of a somewhat harder alloy; it being much less than if the bullet had been cast of 1-40 alloy or even pure lead.

Mushroomed .40 caliber 330-grain paper patch bullet found in badlands of Wyoming.

Another interesting clue as to who might have loaded the bullet into the case was the fact that one could clearly see the impact of powder grains on its base. If there had been a wad loaded under the bullet it would have been very thin or perhaps just a thin disk of lubricant. Possibly, our early-day hunter was trying to get as much powder as possible into the cartridge case and so omitted a thick wad.

Now, finding a spent paper patch bullet in the enormity of the area known as Badger Basin, was truly akin to the needle in the haystack. However, as I looked around it became clear how the bullet ended up where it was. The obvious place to shoot from was a small collection of rocky outcrops that were about 200 yards from the saddle where the bullet was found. Given that distance, a bullet from a 40-70 would more than likely completely penetrate a buffalo, side to side, but given the elastic nature of buffalo hide, would be captured just under the hide on the other side. This has happened to me personally when shooting buffalo with black-powder rifles. When the animal was skinned, the bullet would have dropped out on the ground and obviously went undetected by the hunter or skinners, otherwise it would have been “re-cycled” into another new slug at camp. Close to 150 years later, Sheryll and I stumbled across it.

The scouting camp in Badger Basin; our old reliable 1970 GMC pickup in the foreground.

We checked closely in and around the “hide” to see if we could find any empty cartridge cases. We did, but not from our buffalo hunter; there was a single 25-35 WCF case lying just outside the hide walls where the repeater it was shot in probably ejected it. Obviously, much later in time than the .40 caliber rifle used to fire the slug we were looking at, this cartridge case might have accounted for a mule deer or antelope long after the buffalo were gone from Badger Basin. The rock hide was in such a good strategic spot for hunting, being situated on the way to a good water hole, that I was surprised we didn’t find more “modern” cartridge cases than we did. The absence of any old black powder cases did make sense, however, as the old-time market hunters usually saved their brass for reloading.

The .40 caliber bullet base showing clearly the impressions from impacting powder grains.

After finding the slug and doing some quick mental backtracking, I wondered if we could locate any remains of what the hunters had been shooting. My inclination was buffalo or elk, as a deer or antelope would not have had the tough hide to capture a 330-grain .40 caliber bullet fired from 200 yards away. Looking at the lay of the land and the typical way that bones “migrate” away from a kill site due to weather and predators, I went to take a look at a coulee that opened out onto the lower bench. Sure enough, after a bit of scouting I found some backbones that had the typical high projections that clearly identified them as bison backbones. Some were buried fairly deep in dirt, and no, I didn’t find a skull, but that didn’t surprise me. Skulls were still being found in some remote areas as well as horn caps; I’m sure someone had beat me to the skull years before.

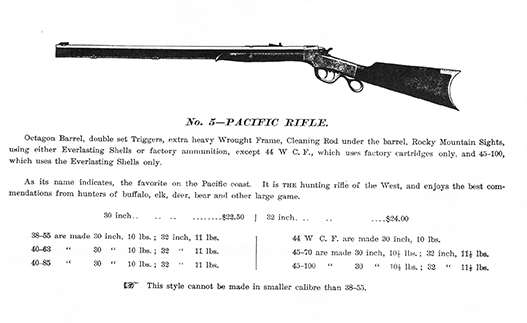

Looking at the old bullet made me really speculate as to what rifle it had been fired from. Judging from the narrow land and wide groove impressions on the slug, I ruled out a Winchester barrel immediately. Buffalo hunting with a High Wall, short of one made by the Browning brothers in Utah, was not at all probable given the time frame of buffalo being in the Big Horn Basin. A Sharps or Remington sporting rifle in 40-70 would seem to be the more likely choice; an early 40-70 or 40-85 Ballard Pacific wouldn’t be out of the question, either.

Probable firing position of the hunter using the .40 rifle.

Coulee where the buffalo bones were discovered.

Regardless of what rifle was used, I would wager that our frontier hunter anchored whatever he was shooting at, given the healthy mushroom on the paper patch bullet. A few years ago, Sheryll and I had the good fortune to hunt buffalo in Nebraska with old friend, John Hansen. I used a 45-70 Ballard Hunter’s Rifle and the bullet was the 457193 Lyman 420-grain flat-nose, seated out to accommodate a 70-grain charge of 3Fg Swiss powder. The bullet was cast 1-20 and the cow buffalo I shot was roughly 150 yards away. One shot through the heart put her down for keeps and when we skinned the cow, the bullet was under the skin, well mushroomed, on the far side. It looked remarkably like this .40 caliber paper patched bullet.

This old bullet had an intriguing story to tell. Some of it we are simply surmising and other parts we can draw from educated conclusions. Either way, it felt to me like a direct connection back to some frontier hunter and an amazing learning experience. And, in case you are wondering that bullet was put back in the exact location that it was found in. It had told its story and needed to be out in the hills, not gathering dust on some shelf. If you feel really lucky, head out into Badger Basin and see if you can find it!