The Wyoming Schuetzen Union’s “Center Shot”

Measuring Black Powder

column By: Steve Garbe |

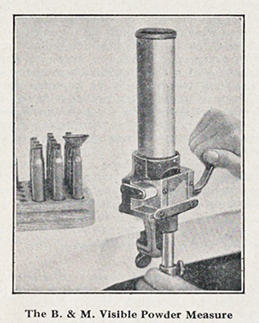

“Due to its unique construction, the B&M Visible Powder Measure is by far the most accurate tool of its kind available. Most powder measures of to-day have but one hopper which feeds directly into a measuring chamber, with the result that the height and density of the powder column in the hopper have a direct influence on the weight of the powder charge thrown. Thus a full hopper of powder throws a heavier charge than one a half or a third full. The B&M Visible Powder Measure overcomes this fault because the main hopper is not connected to the measuring hopper. The powder is fed from the main hopper into a secondary hopper of charger reservoir and from this into the measuring chamber. The charger reservoir is disconnected from the main hopper when it is connected to the measuring chamber. Thus the height of the powder in the main hopper has absolutely no effect on the weight of the charge thrown. This feature largely accounts for the remarkable accuracy of the B&M Visible Powder measure. Successive charges thrown by it vary so slightly in weight that only by the most careful and tedious manipulation of a set a balances can the handloader obtain more uniform powder charges. It is the most accurate powder measure available.”

Make no mistake; the Belding & Mull-style measure is very little affected by the height of the powder in the main hopper, but affected it is. So, I made a point to throw no more than 10 charges and then refill the hopper. More consistent weights of powder were then achieved, but wait…wasn’t weighing black powder taboo? It most certainly was, and years ago more than a few gun writers said so in print. Back then, I didn’t weigh every charge of powder and used my “no more than 10 charges” technique as my standard. I enjoyed relatively low Standard Deviation and Extreme Spread readings on the chronograph and I was happy; at least, until I noticed the different weights of powder amongst different lots and even between the cans from the same case of powder.

Many fellow shooters used different cans of powder, albeit of the same granulation and brand, indiscriminately when loading a batch of ammunition, possibly even using part cans to make up the necessary amount. They, of course, were using stricken measure, and this technique would help eliminate some of the introduced variables, but not well enough to my way of thinking. Early on, I would use only one full can of powder for a “lot” of ammunition and not mix batches or cans. Moisture content can affect the performance of black powder and I wanted my powder to be as uniform as possible for each cartridge. I also noticed that charges from different cans in the same case lot would vary in weight, sometimes as much as two to three grains. So, weighing black powder as a primary measurement was going to be full of unacceptable variation when different cans were used. This is probably where the advice to always use “stricken” measure came from. However, I wanted a way to verify powder amounts other than relying on the powder measure itself. Weighing the charges was the obvious solution, but only when using powder from one particular can. When one changes cans, a new weight must be established.

This isn’t as hard as it sounds. Simply weigh five or better yet, 10 sample “stricken” charges from a new can to establish an average weight, and then set the powder scale to that amount. I weigh every charge for my match ammo but will fully understand those who think it is unnecessary. In my mind, I’m eliminating a possible variable and weighing charges after they are thrown definitely shows up with lower Standard Deviation and Extreme Spread readings on the chronograph. I’m convinced that knowing you have eliminated as many variables as possible is an advantage, if for no other reason than it helps your mental game.

By the way, I use the chronograph religiously when doing load testing and development. I’m well aware of the opinion that low Standard Deviation and Extreme Spread numbers don’t always guarantee an accurate load, but I have never had an accurate load that didn’t have low readings. To my mind, if a load you are testing has high Standard Deviation but shoots well, an inordinate amount of reliance on “Harvey’s Law of Compensating Errors” is being done. Only by eliminating variables, starting with powder charges, are we going to develop a truly reliable load that is capable of being duplicated.