The Hide Hunting Exploits of Harry "Sam" Young

feature By: Leo J. Remiger | June, 21

Harry Young was born in Cape Vincent, New York, in 1849. In 1863, he ran away from home and made his first stop to visit his brother Bill, who was working as a machinist in Fulton, New York. Bill loaned him the fare to travel to New York City. After working as a bellboy in the Weldon Hotel, he relocated to New Orleans, worked his passage to Memphis on the old steamer “Bismark” and from there made his way to Fort Smith, Arkansas. From Fort Smith, he traveled to Fort Gibson. While at a stage station in the vicinity of Fort Gibson, Young hired on with a surveying party, which was engaged in running a railroad survey from Fort Smith, Arkansas, to the main line of the Atlantic & Pacific Railway at Antelope Hills, 300 miles south. While attempting to survey across some Indian land, their survey was halted at Prairie City, the current terminus of the Atlantic & Pacific Railroad. The men were paid off and the survey party disbanded.

Young and a man named Frank Emmons walked from Fort Gibson to Chetopa, Kansas, and found employment with Bill Henderson, cutting and pitching hay. After difficulties with the boss, Young quit this job and returned to Chetopa where he hired on as a herder for an outfit owned by a man named Pancake. A month later, Young hired on with a man named Hamilton who had purchased 200 head of stock cattle out of the herd owned by Pancake. Together with a Mr. and Mrs. Sutherland, they drove the cattle to Hamilton’s ranch near Arkansas City. After being paid off, they went south into what is known as the “Cherokee Strip.” “The Strip” was a piece of land owned by the Cherokee Indians, and was about 100 miles square. It adjoined Howard County, Kansas, five miles south of the town of Elgin.

Young and Sutherland had heard that the U.S. Government intended to buy the Strip and allow 160 acres to each person having a homestead or squatter rights on the land. Young and the Sutherland family settled on adjoining pieces of land, but lived together. However, before the government could buy the Strip, some Osage Indians sold their lands in Kansas and bought the Strip from the Cherokee. When the Osage arrived to take possession, they found the land occupied by white settlers. The Osage promptly appealed to the government, who then notified the settlers to vacate. In the spring of 1867, the Osage Indians established its new agency 40 miles south of the Kansas line. Twenty white men were employed on the agency, of which Young was one. When he tired of agency life, Young headed for Wichita, Kansas. He remained there a short time and then went to Newton, the terminus of the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad (AT&SF). From Newton, he followed the extension of the AT&SF railroad to the next terminus, Larned, Kansas, being employed by the railroad. After a short time, he relocated northward to Hayes City and arrived there in 1868. Young eventually left Hayes City and moved to Abilene.

One of the first stories regarding hunting that Harry Young wrote of was his first deer hunt in 1866, while living on his land in the Cherokee Strip:

“One bright morning… Sutherland and I went together on a deer hunt; he took his Spencer carbine, and I borrowed a heavy muzzle-loading rifle, equipped with a set trigger. I was now to have my first experience at deer hunting.

Sutherland proceeded with caution along the top of a ridge or hill, and I along the foot. I had not gone far when I saw three deer pawing in the snow, looking for acorns. They had not seen me, and I quickly decided that here was the chance to secure my first deer. Unfortunately, while in the act of taking aim, I unconsciously touched the set-trigger, resulting in the load going off in the ground about ten feet from me. Hearing the shot, Mr. Sutherland ran down and asked me if I had hit a deer. Not wanting him to know that my rifle had been discharged accidentally, I replied: “Yes, I hit him.” Whereupon he began to search, but no deer could be found. Mr. Sutherland scolded me severely for my poor marksmanship, and we returned home without any game.”

In the fall of 1870, Young had relocated to Ellsworth. He found work with the Toole brothers. These brothers had purchased 800 head of young stock cattle and planned to make a drive to Montana and establish a ranch. They intended to winter the cattle over on the Arkansas River, approximately 125 miles west of Fort Dodge.

During the drive from Ellsworth they had much trouble with buffalo. The buffalo herds stampeded the cattle herd on several different occasions during their drive. Young estimated there were “hundreds of thousands” of buffalo in the country at that time.

When the outfit reached their winter’s range, they constructed dugouts to live in. Young wrote that they were constructed by cutting into a bank or hillside to the size desired, then roofing it over with ridge and roof poles, finally covering the ridge and roof poles over with sod and dirt. The entrance was built up with sod and an opening was left for the door. Young goes on to mention:

“One night during the first week we lived in the dug-out, we were awakened by one of the cattle walking over the roof. Before many minutes had elapsed, she fell through up to her body and we experienced great difficulty in getting her out. Had she fallen all the way down, or through, she would have landed on my bunk, with probably fatal results to both of us.”

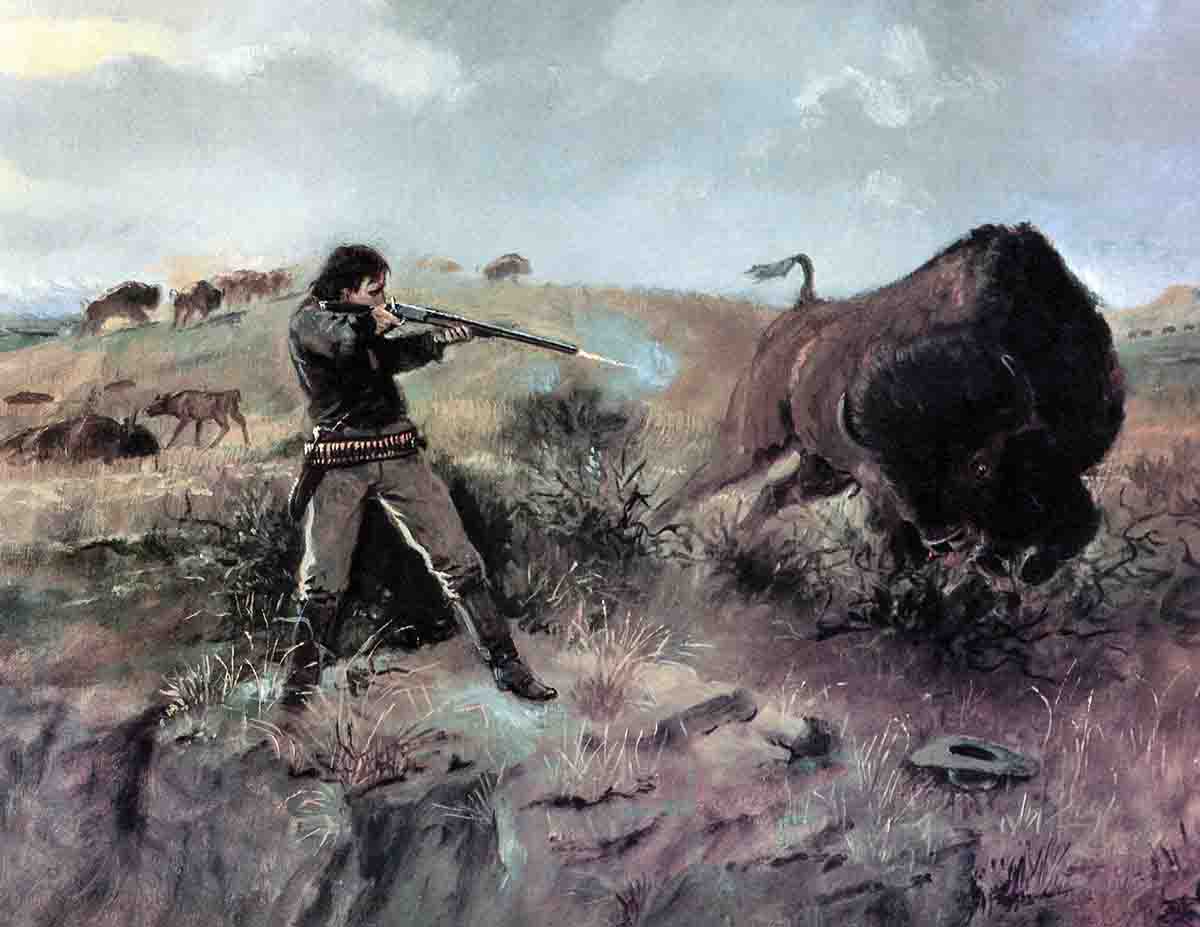

On a bright and cold winter morning, while the men were in the dugout, they heard, and then saw an immense heard of buffalo moving toward the river for water. Toole mentioned to the other men that Young had never killed a buffalo before and here was his chance.

Young picked up an old Spencer carbine and hid himself in a clump of willows near the river, in sight of the dugout. In a few minutes, the herd arrived and in a very short time, hundreds of buffalo were on all sides of him. Young described the situation like this:

“For some reason, however, they did not see or scent me. I became nervous and yelled at them. In a moment everything was in confusion – never shall I forget that grand sight. Every buffalo in the herd seemed to be aware of his danger and immediately stampeded toward the hills. One old bull came within two feet of my hiding place. Although I was very much frightened, I pointed the gun at him and pulled the trigger. I then made a run for the dug-out without waiting to see the result of my shot, completely forgetting that there were other loads in the magazine of the weapon. The buffalo did not immediately fall, although I was sure that my shot had struck him. When near the dug-out I saw the boys looking at a point back of me, and following the direction of their gaze I saw the buffalo in the throes of death. “Why didn’t you take another shot at them?” asked Mr. Toole.

“Because,” I replied, straightening up as proud as a peacock, “one shot is enough for a green hand.” Later I became quite a buffalo hunter. The four months that I remained with the Toole brothers, I killed forty-six of these animals. Each herder carried a gun and ammunition, and we were supposed to kill all the buffalo possible; some we used for food, but our principal revenue was from their hides. The prices were three dollars and ten cents for bull hides and two dollars and ten cents for cow hides. Mr. Toole told me afterward that during their winter stay there, they had killed and sold enough hides to pay the wages and expenses of the men for the entire winter. The almost complete extermination of the buffalo was caused by professional hunters, who were continually killing them for their hides. These hides were hauled to the nearest railroad station, where they were sold and later shipped to England, where they were made into belting for machinery. Few were made into buffalo robes, as the hunters did not have the time to tan them.”

When Young left the Toole brothers, he picked up employment as a buffalo skinner for Kirk Jordan. Young said that Jordan had three four-horse teams and 20 men in his employ and was one of the most successful hunters of this time. Young also stated that Jordan held the record “stand,” having killed a hundred buffalo in one place. He also mentions that he (Young) was the first to suggest skinning a buffalo by mule power:

“I went skinning buffalo for Kirk Jordan and was the first to suggest and put into practical operation the skinning of buffalo by mule power. This was done by cutting the hide around the neck, down the belly and up the legs, after which the skin was started a little. A large sharp steel pin was then driven through the buffalo’s nose and into the ground; then a hole was cut in the back part of the hide at the neck, a chain hooked in the cut and by means of a collar, hames, traces and single-tree, with which the mule was equipped, the hide was pulled off the buffalo with the greatest of ease. Of course, by this operation much of the flesh adhered to the hide, but the market value of the latter was not affected in the least. After the hides had been staked out until partly dry, they were loaded on wagons, which were equipped with a rack similar to a hay-rack, also using a binding pole. In this way a great many hides could be hauled in one load. These wagons were drawn by four animals to the nearest town on the line of the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe railroad, and sold at the prices previously mentioned. Anyone who was a good hunter and who had an outfit, could make a great deal of money in this business as long as it lasted. Kirk Jordan made thousands of dollars.

“Kirt Jordan, the great buffalo hunter, finally went wrong, and became a horse and mule thief. The U.S. marshal arrested him for stealing government mules, tried and sentenced him to Leavenworth Government Prison for ten years. An officer and two men, with Kirt handcuffed, started for Leavenworth, Kirt sitting in the seat with the officer, and the soldiers sitting in the seat at his back. Kirt requested the officer to unhandcuff him as he wished to wash himself in the toilet. The officer did so, when, as quick as lightning, he grabbed the officer’s six-shooter from his scabbard and shot him dead. He then shot one of the soldiers, and jumped through the open window to the ground, lighting on his head and breaking his neck. Poor Kirt was a good fellow, but, like many others, after his occupation as a buffalo hunter ended, he could not resume his occupation as a teamster, and accordingly went bad.”

Harry Young tells another entertaining story of Billie Brooks, the notorious gunman of Dodge City:

“Billie Brooks, the gun man of Dodge City in the early seventies, was one day riding on the construction train from Dodge City to Sergeant. The conductor, coming through the coach, asked him for his fare. Brooks replied by drawing his six-shooter, saying, “I travel on this.” The conductor passed on. After he was through with his fare collecting, he went forward to the locomotive and instructed the engineer to slow down at a certain point. Getting his shotgun, he dropped off the engine and caught the last car, in which Brooks was seated. Approaching from the back, he called out, “Brooks, the fare to Sergeant is $2.75.” Brooks looked over his shoulder, and seeing the shotgun pointed him replied: “To whom do I pay the money?”

Just then the brakeman stepped in. The conductor said, “Pay the brakeman, and also hand him your six-shooters, and when you arrive at Sergeant, the agent there will return them to you.

Brooks did so. Meeting the conductor the same night in the dance hall, Brooks said, “Old man, you are a good fellow and a good conductor, and I want to be your friend.” Thus the matter ended.

Brooks in future days became a horse and mule thief, and was chased by a posse to a dugout near Wichita, where he stood the posse off for two days. He was finally induced to surrender with the promise that he would be tried by the law in Wichita. He was told to leave his guns in the dugout and walk out unarmed. He did so, and was mounted on a horse and taken to a nearby tree and hanged. Thus ended Brook’s career as a gun man.”

Regarding the subject of gathering buffalo bones, Harry Young had this to say:

“One year after the Santa Fe railroad had been constructed along the Arkansas River, there came into that country an old man with a two-horse team, who quietly began the gathering of buffalo bones, hauling them to the railroad and piling them in great heaps. The boys all laughed at him and dubbed him “Old Buffalo Bones.” The old fellow enjoyed their joking him and kept on with his gathering. Later he procured another team and sent east for his son to drive it. The following year this man had many great piles of bones ready for shipment east. The Santa Fe railroad being anxious to load their empty cars eastward, gave him a very low rate and laid side tracks to the piles. The records at Dodge City show that this man, “Old Bones”, shipped three thousand carloads to Philadelphia, where they were used in sugar refineries and for fertilizing purposes. This old man, at whom we laughed, made a great fortune in two years.

To give the reader an idea of the number of buffalo killed in that country, the railroad records at Dodge City show that two million buffalo hides were shipped from that station alone, and it is estimated that there were twenty-million buffalo killed between the boundaries of Montana and Texas.”

Our final extract from Hard Knocks concerns Harry Young’s attempt at capturing buffalo calves and marketing them:

“Four of us went down river to a ranch kept by a man named “Prairie Dog Dave,” for the purpose of catching buffalo calves, our intention being to ship them east by rail. Insofar as our catching the calves was concerned, we were very successful. They were caught in the following manner:

Mounted on our horses, we got as near the herd as possible, unseen, then suddenly riding after them. The cows and young calves, when the herd was stampeded would naturally drop to the rear and the cows would remain with the calves until closely pressed, when they would desert them. We would then jump from the horses, throw the calves down and tie their legs.

At this season of the year, the calves were about two months old. We succeeded in catching twenty head, and finally hauled them to the ranch by wagon. However, we soon discovered that we could not tame them, nor could we get them to eat, so out of pity we let them go. Before doing so, however, two were drowned in a spring near the ranch. We had picketed them out, taking the ends of the lariat and fastening it around their necks, then taking the middle of the lariat and attaching it to a picket pin, which we drove into the ground, but the poor little fellows became entangled in it and fell into the spring, where they were drowned. Two others escaped with a sixty-foot lariat, which we never recovered, and I shall always believe that someone stole the lariat and allowed the calves to get away. Our venture was not a success. We became discouraged and gave up the business.”

Is Hard Knocks fiction or is it a true story of Harry “Sam” Young’s life in the West? Hopefully, some of these extracted paragraphs will make you want to read the book and make that determination yourself. It is full of amusing and entertaining anecdotes of the West, mentioning famous and infamous personalities you may have heard of, and a great many more you certainly have never heard of. It is typical of a reminiscence written without benefit of a diary or verification of actual dates. As a young man, he was constantly on the move, working temporary jobs where they were available. Aside from the obvious inaccuracies, there is no reason to believe that he did not witness the events he recorded, because, after all – “Truth is stranger than fiction.

Young, Harry (Sam), Hard Knocks – A Life Story of The Vanishing West, Wells and Company, Portland, Oregon, 1915