The Wyoming Schuetzen Union’s “Center Shot”

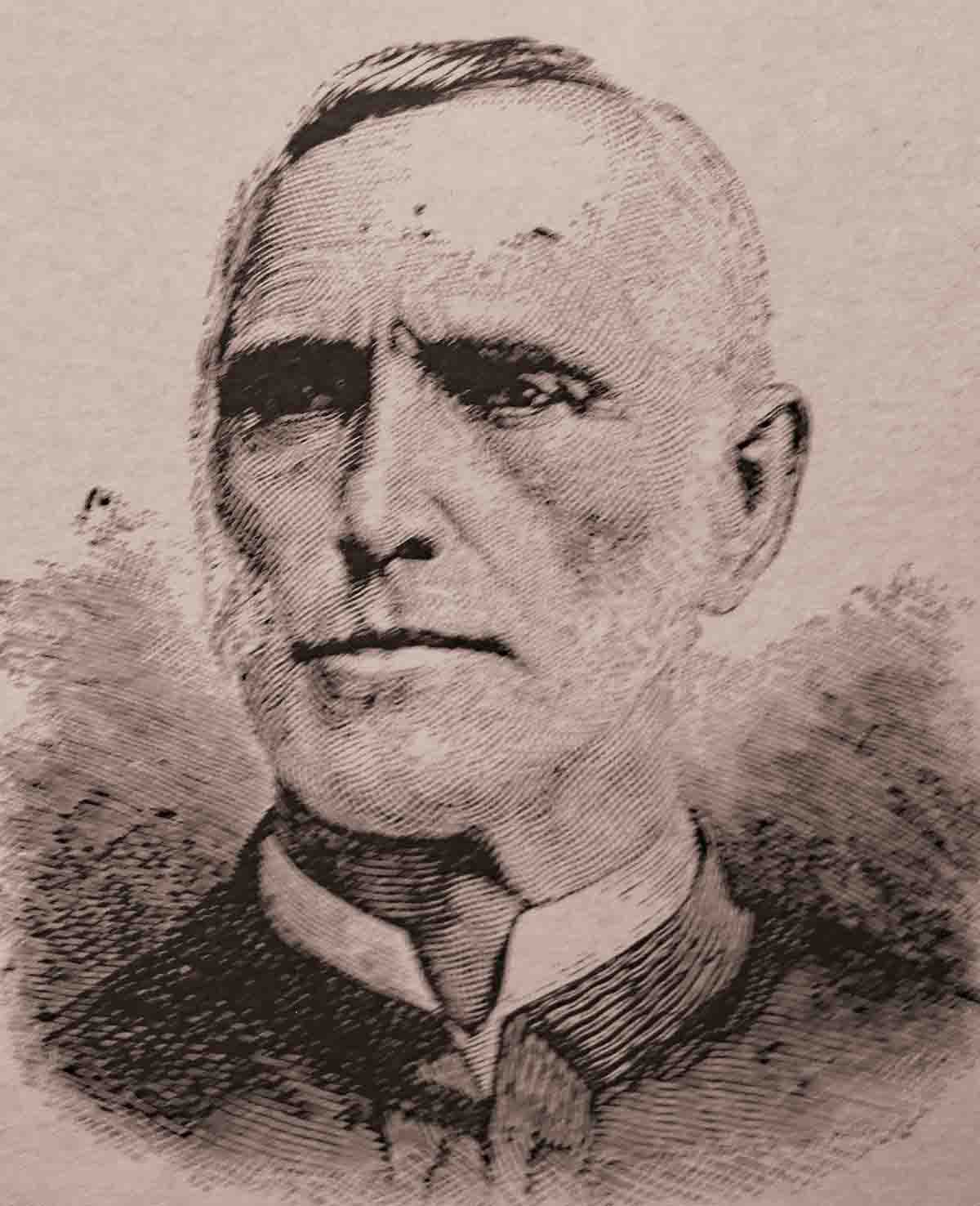

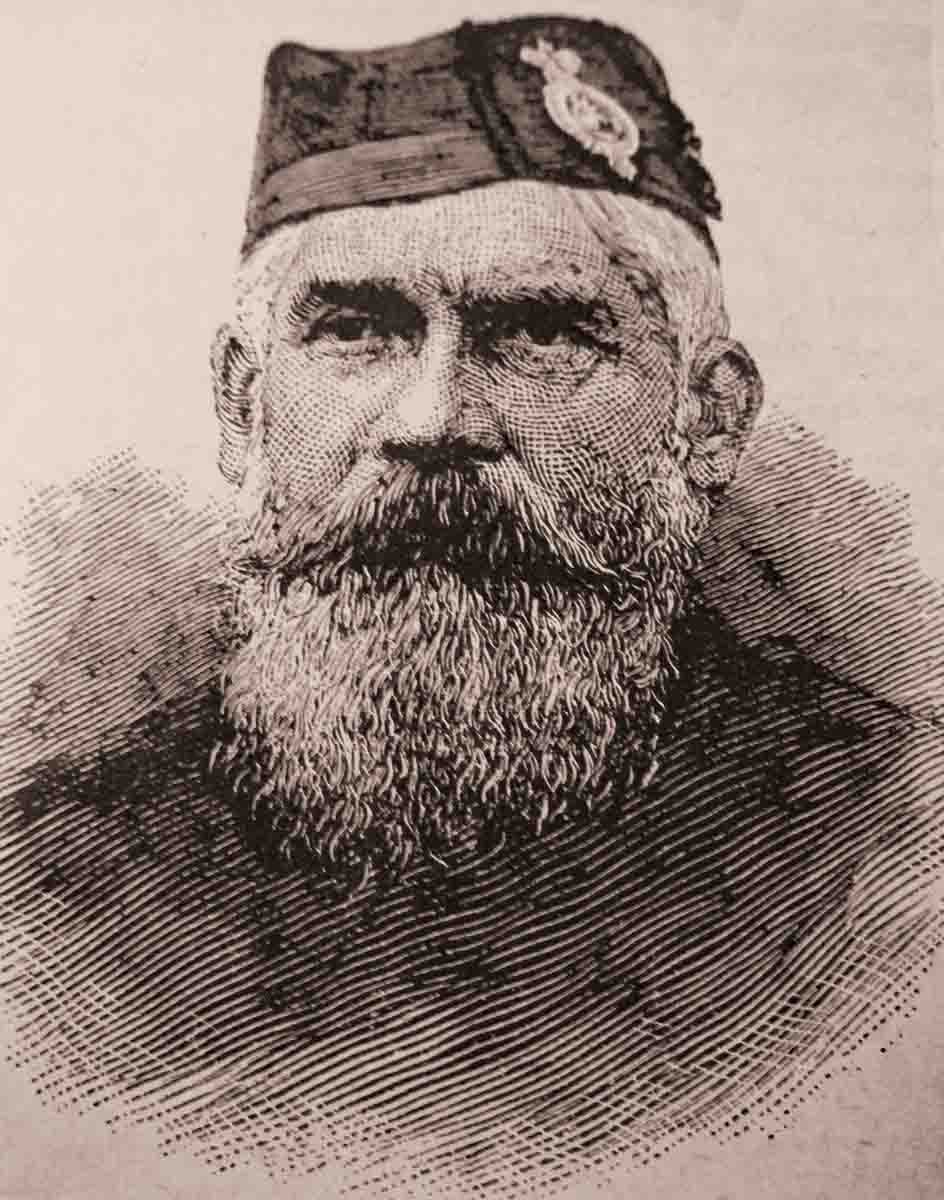

John Bodine, "Old Reliable"

column By: Jim Foral | June, 21

These front-page words of a Forest and Stream staff writer represented the realistic expectation. The thought of facing either man – Bodine in particular – with something to lose on the line, was a pretty daunting prospect. Those who’d faced him before were aware that his nerve would outlast theirs, and the contest’s outcome was not just likely, but a foregone conclusion with little to be done about it. Bodine was that imposing – and that good.

John Bodine was born in Ulster County, New York, near the village of Highlands in 1825. He was descended from the Huguenot Patentees, the original seven-family group that settled on a 40,000-acre patch of topsoil on the west side of the Hudson River, in the valley of the Walkill. It was purchased from the Esopus Indians in 1677. Young John was brought up as a farmer and practiced this occupation until the age of 29, whereupon he left the farm and hired on for two years with the New York and Erie Railroad. Later, he took a clerking position at the National Bank of Newburg, New York, and relocated there.

Sometime after this he became engaged in the freighting business and ran barges on the Hudson River from Highlands to New York City. Another John Bodine, likely his father, was active in the same business, in the same vicinity a generation previously. This business suited both Bodines and the junior built it up into a rather profitable venture.

Before leaving the farm, young John became connected with the New York State Militia and spent the next 35 years in that service, attaining a Colonel’s rank in the 92nd Regiment. At 20-years-old, John became enamored with rifles. His exposure to the region’s 20- to 40-pound muzzleloading cap lock rest rifles instilled in him an appreciation for precision and a quest for rifle accuracy that persisted throughout his life. Along the way, he sampled the different shooting disciplines and was particularly smitten with the early cartridge rifles and their long-range capabilities.

Bodine was one of the original members of the Amateur Rifle Club of metropolitan New York City. The club had been formed in October of 1872, and was particularly devoted to long-range shooting, and was not geared toward the customary military style of rifle shooting. Theirs was the first club to be affiliated with the newly-formed National Rifle Association (NRA).

The NRA had no rifle team, per se, so when the Irish Rifle Association’s challenge for a rifle match appeared in a New York newspaper in early 1874, the 67-member Amateur Rifle Association answered on behalf of the American NRA and all Americans. The planned long-range match in the British tradition between teams of the two countries was intended to be an expression of mutual goodwill and universal fellowship.

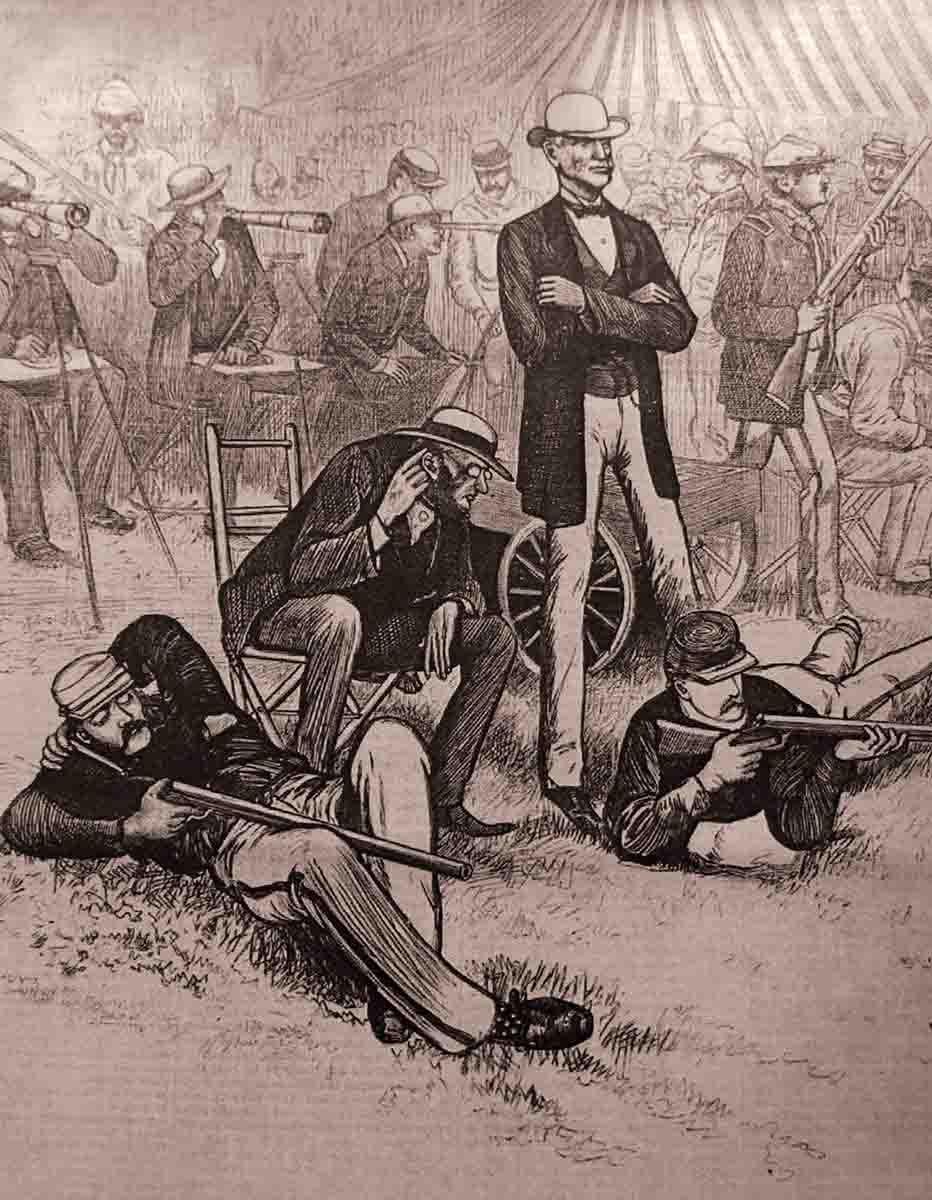

Never minding that none of the qualifying Amateur Rifle Club members had ever fired a shot at a target beyond 600 yards, they began to equip themselves with suitably-developed rifles and ammunition. They then practiced industriously for the September 26 match at the newly-extended Creedmoor Rifle Range. The firing members of the club received the Irish visitors and did their best to make them feel welcome.

On September 19, a preliminary match, the “Remington Diamond Badge” was shot. Rather than simply spectate, the Irish team members were encouraged to enter the 500, 800, and 1,000-yard event and were offered the use of Remington rifles and cartridges. Despite the gun’s unfamiliarity, the Irish shot them acceptably and a couple of them placed. John Bodine got his elevations mixed up and was off the target for the shorter shots. The Forest and Stream correspondent covering the match summed up what most people already knew: “We are quite willing to believe that on the occasion of the International Match Capt. Bodine will get his elevations just right, for there is no steadier, nor better, no more lasting shot than he is.”

All things considered, the New Yorkers actually representing America in the main event match made a creditable showing of themselves in the 800- and 900-yard phases of the contest that the Irish had expected to be more of a rout of the green Americans. As they drew back to the thousand-yard line, the “Yanks” were actually relishing a slight lead. The Amateur Rifle Club crew was rattled by the cacophony of boisterous cheers from the thousands of spectators in attendance. L.L. Hepburn and General Dakin both began their string with misses, and Dakin made two more in his 15 shots. When Dakin missed his last shot at a thousand, the vast crowd let out a loud collective moan.

The imperturbable Col. Bodine, because of his proven steadiness under pressure, was selected to shoot last. The Irish score was 931 and the Americans were now a point behind. A few minutes before heading to the firing line, Bodine had a bottle of sun-heated ginger ale burst as he opened it. He received a bad cut on his firing hand that only heightened an already stressful occasion. Bodine needed a hit on his last shot and the upstarts from America would beat the rifle champions of the British Isles. If he missed – his team would lose. The onus was on Col. Bodine as he stretched out his tall frame into his signature prone position, gasped the pistol grip of his rifle with a handkerchief-bandaged hand, and pointed the Remington down range. He touched off 95 grains of Hazards Fg, and in due time the slightly hardened .45 caliber 550-grain bullet arced across the half-mile span, perforated the white target paper and impacted the iron backer. Three seconds later, the now silent crowd heard its ping. The hoped for white disc took an eternity to appear, but when it did it signaled a bullseye and a win by three points for the Americans. As it is always said on these occasions, “…and the crowd went wild!” The sky was reportedly darkened for the many thrown hats. General Wingate would later write that “men danced and thumped each other on the back and whooped and yelled and acted like crazy people.” They were like crazy people who had just witnessed the most dramatic finish in the history of American marksmanship, John Bodine’s finest hour, and his famous shot known reverently thereafter as “The Shot” – the shot that also bolstered his nickname “Old Reliable.”

Clear into 1875, the gunmaker Remington repeatedly used an illustration of Bodine’s 800-yard target along with the shot-by-shot tally of his 74 X 75 score. They filled the balance of the quarter page ad with a full-length graphic of the rifle. A sly inclusion was the name of Bodine, Fulton, and Hepburn, the three team members who used a Remington rifle in the win. An excerpt from the Army and Navy Journal wrote of the ad: “…may be seen as the most effective advertisement we have ever come across of the shooting of a Remington breech-loader.”

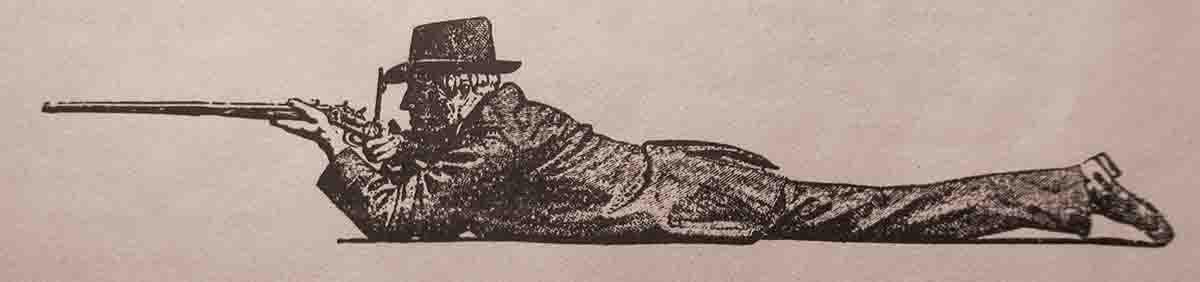

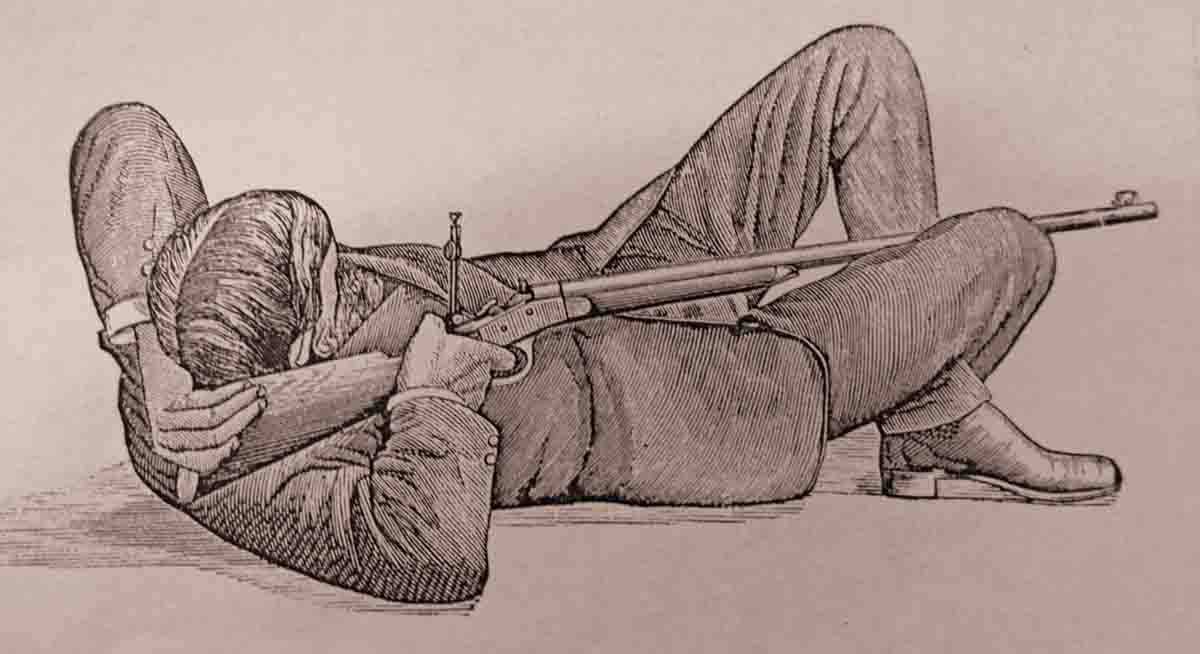

The weight and heavy recoil of the new style of long-range rifles motivated most shooters to take up the back, or supine position as a way to manage their 10-pound shoulder bruisers. For most, this proved steadier than prone and there was therefore less trepidation with trigger squeeze, both important considerations. As the merits of the back position became better known in the early 1870s, it became favored almost universally. Most shooters facing the 1,000-yard target did so on their backs, in whatever of the various stances worked best for them. Henry Fulton’s variation was unorthodox enough that it was named for him. Holdout John Bodine shot from prone, as did his teammate Judge Gildersleeve. They were among the only five percent of long-range competitors that preferred to shoot these heavy rifles conventionally from prone, on their stomachs.

Early in the spring of 1875, the Irish club challenged the American champions to a rematch to be shot at the Dollymount Range near Dublin. Officially, the invitation was received on April 15, 1875, for a match to be held on June 29.

After the 800-yard segment on match day, the Americans had forged ahead with a confidence building lead. With a boisterous crowd estimated at 30,000 Irishmen fueling the pressure, Col. Bodine’s 10-shot 900-yard string was undertaken and completed in that nerve-rattling din. Again, “Old Reliable” lived up to his name and ran up 14 straight bullseyes, finishing with a “center” for 57 of 60 points possible, a remarkable feat, distractions considered. Remington used an image of the target (together with the detail that it was accomplished with a Remington rifle) for eight consecutive Forest and Stream issues.

With nothing on the line this time, Col. Bodine again fired the American’s final shot at 1,000 yards – a bullseye. The Americans had soundly beaten the Irish on their own soil, the score being 968 to 929. Col. Bodine’s fellows at the Hudson River Masonic Lodge presented him with a magnificent diamond-studded Maltese cross to commemorate his part in the victory.

During the Creedmoor Match of 1874, three Americans (Bodine, Fulton, and Hepburn) used Remington rifles. Remington’s 1875 post-match advertising listed two more converts to the Remington single-shot preference.

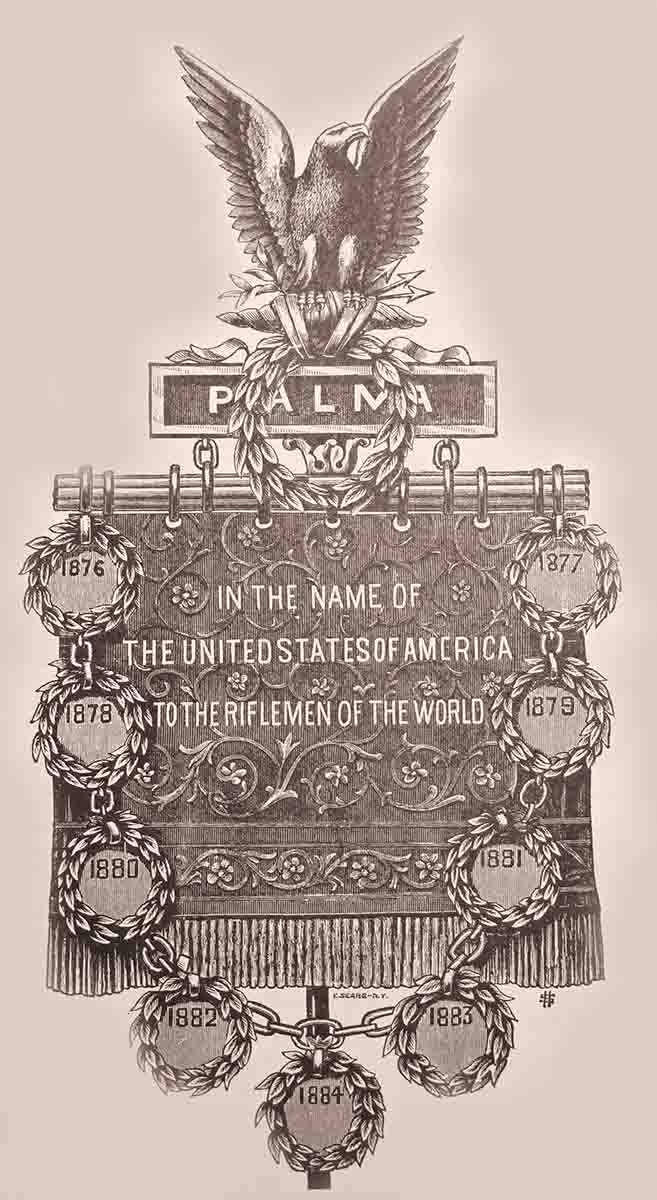

The Centennial Year of 1876, caught the United States in a celebratory mood. At the suggestion of Judge Henry Gildersleeve that they should host another international match, invitations were sent to nations with rifle associations. England bowed out, but Scotland, Ireland, Canada, and Australia pledged teams. They would contest for a new prize that would come to be known as the “Palma Trophy.” The American National Rifle Association had commissioned a trophy to be awarded to the winning team of the Centennial Match. It remains yet an honored tradition to compete for the Palma Trophy by international military rifle teams.

The American team had been selected by tryouts and had gone through the rigors of organization and practice without Col. Bodine or Judge Gildersleeve competing to make the cut. After an early team practice session had gone badly enough that the Forest and Stream correspondent present used the words “went all to pieces,” Gildersleeve and Bodine recommended that to “strengthen the team,” they should replace Leslie Bruce and another “weak sister.” Any hard feelings that might have resulted from this strong-arm roster switching was not the sort of news that got broadcast in the press.

The American team dominated the competition and when the black-powder smoke had cleared on September 13, 1876, at the Creedmoor Rifle Range, the Americans had scored 3,126 points. Ireland was not strong enough but only trailed by 22 points, followed by Scotland, Australia, and Canada.

In 1877, Great Britain organized a team of its subjects drawn from every corner of the British Isles. Sir Henry Halford then took the team to Creedmoor and faced the best America could put together on September 13-14. They got beaten nicely in the end, 3,334 to 3,242. A consequence of the 92-point margin of defeat was the foreign team’s avoided agreement to a rematch for a good long time.

Col. Bodine failed to post at the American team tryouts on July 24-25 and he didn’t publicly disclose whatever reasons he may have had for the decision. He did however, make himself available to celebrate and socialize in the post-match festivities. He was even a member of the group that showed the visitors the New York sights, including a shooting demonstration by Ira Paine, who plucked feather-filled glass balls from the air with his shotgun.

It shouldn’t be automatically assumed that an avid competitive shooter of championship level would naturally be considered a gun enthusiast, but in Col. Bodine’s case, this was no doubt true. He was an eager sportsman and an ardent collector. It was written that he had, in 1874, a “collection of modern sporting guns that is perhaps the finest in the states.” In 1876, he ordered a pair of deluxe Model 1875 Sharps long-range rifles. It is also a matter of record that in 1877, he took delivery of a high-grade Greener hammer double shotgun, with which to shoot partridge in the Catskills. Bodine provided more details in a testimonial provided for the gunmaker. It was a heavy 10-pound, 10-gauge gun with 32-inch barrels, one side choked “modified” and the other “choke bore.” Its cost in 1877, was $400 and the word was that Bodine shot it “as well as he did a Creedmoor rifle.” That same year, New York City Greener agent, H.C. Squires, had for sale a “Dougall (London made) top-lever 12-bore with all of the improvements, made to order by Col. Bodine, of highest quality with original invoice.”

Unexpectedly, Bodine spoke fluent “shotgun.” On the pages of Forest and Stream, he would occasionally detail loading shotshells; powder, shot and wadding for various sporting purposes as proficiently as he did match-quality black-powder rifle cartridges.

With the Creedmoor-style of shooting beginning to slack off, Col. Bodine was in demand to serve as a captain and leader of several American military rifle teams that were competing in international events. This discipline had supplanted the long-range match rifle competitions. In his career as a rifleman, he had acquired and polished the necessary skills for the job.

In 1877, Judge Gildersleeve put together in book form a series of articles he’d written for Spirit of the Times, a widely-circulated New York City sporting newspaper. His Rifles and Marksmanship was a treatise on what the title suggests, but more specifically it served as a tutorial for aspiring long-range marksmen looking for guidance on the new swing in rifleman circles, from the voice of authority.

Another guiding light, Bodine contributed a chapter titled “Team Practice,” which combined his insight and experience over the years actively competing. Bodine offered his advice on working well as a team unit. He authoritatively examined the role of the spotter, how to best utilize each man’s strengths and deal with their weaknesses. Bodine’s treatment of the material and his ability to masterfully communicate it, made his first chapter one of the more helpful and significant in the book.

After a lull in rifle practice, in April of 1880, an American team accepted the invitation from the Irish Rifle Club to a rematch at their Dollymount Range that summer. Col. Bodine accepted the role of captain of the team that was independent of NRA sponsorship. The team consisted of veteran Ransom Rathbone, prominent marksman Milton Farrow and a few fresh faces. The Americans used Sharps-Borchardt match rifles, the lone exception being Farrow who stuck with his Ballard.

The trip was not without its drama. Evidently, Farrow got upset the morning of the match and defected, taking with him team member H.F. Clark of the Empire Rifle Club. The incident (occasioned by conflicting personalities) resulted in a lasting bitterness between factions and a measure of public airing in the newspapers, as well as the rifleman’s press.

Much credit was given to Col. Bodine’s first-rate wind judging in the decisive 1,280 to 1,202 points defeat of the Irish on their home range that June 29, 1880. All during the 1880 shooting season Col. Bodine kept himself very active shooting the events at Creedmoor. At the Seabury Matches in October, Bodine tied for third in the 1,000-yard event and acted as the match’s executive officer. For a good stretch of years in the 1870s and 1880s, the colonel was active in NRA affairs, sitting on committees and board of directors.

After declining an invitation from Great Britain to a long-range match in the spring of 1882, the U.S. issued its own invite to shoot a military rifle competition at Creedmoor late that summer. Team members were selected from National Guardsmen, most of whom came from the ranks of the marksmanship-oriented New York State units. Col. Bodine, a fellow New Yorker, was elected team captain.

It was Sir Henry Halford, Great Britain’s leading rifleman, who in 1881, proposed that an international match be shot with the military rifles. It seemed a logical step in training guardsmen to practice and compete with their national arm. This plan would also benefit national defense and preparedness by way of rifle and ammunition development and perfection. Halford further suggested that the U.S. introduce the national service rifle into a regular international competition program.

It became noticeable that the U.S. team management and administration were not on Col. Bodine’s list of priorities. Indeed, he seemingly made no apparent attempt to coach his men in the niceties of long-range marksmanship – and it showed. Overall, there was a palpable mood of pessimism to the undertaking, one of having lost the match before the first shot was fired. Too, the American underdogs seemed to be intimidated by the brightly-colored uniforms of the English team, together with their imposing military presence.

On the other hand, it was written about the American team captain by a British journalist cruising behind the firing lines – “Col. Bodine is the most military looking on either side. Tall, dignified, straight as an arrow, he looked the very ideal of an officer.”

Match Day – September 12, 1882 – was “terribly windy, gusty and just a bad day to be shooting,” Col. Bodine remembered. The short and midrange matches were shot first. After the 200-yard offhand match, the Americans were down five points, and they dropped nine points at 500 yards, and another nine at 600 yards. They couldn’t count on catching up in the three long-range phases, the 800, 900, and 1,000 yard events. To a man, the British fired these ranges from the back position. The Americans either preferred prone or they hadn’t been shown the merit of the back position. At the end of the day, the visitors from Britannia humbled the colonists at Creedmoor 1,975 to 1,805 points, a 170-point spread. The showing of Bodine’s team didn’t help to maintain his standing in the rather small community of military marksmen, and the sheen of celebrity about him lost some of its luster.

It’s always easiest to place the blame for a loss with the coach, and that’s what happened at Creedmoor in 1882. One British journalist harshly summarized: “Bodine has proved himself to be a flat failure.” Forest and Stream columnist “Nick” jumped on the dogpile and might have printed his post-match assessment of Bodine’s coaching on asbestos paper. “The first blunder of the team was in its selection of a captain.” More caustically now, Nick continued, “The undisputed merit of American arms suffers through the blundering of a man who is foisted into a place for which he is not competent. As a team captain…he had already proven a failure.”

Bodine offered an explanation. Summarized – “It proved to be a hopeless task to coach a military team on any plan applicable to former long range contests.” The colonel proved himself capable of self-defense. With a good point, he criticized the British rifle sights, which were “really above the military grade,” whereupon the Brits played upon him the “sore loser” card. Bodine considered the Englishmen’s rifles, single-shot Farquharsons with Metford-rifled bores and Gibbs handwork lavished upon them “unfit for rough military issue.” His own team was found guilty of monkeying with their cartridges. “With men changing their powder charges from day to day, coaching was a useless endeavor.” Bodine knew something about this that the men were unaware of; he and Thomas Dolan had recently spent some weeks at the Remington factory working up reliable loads for the .44 and .45-caliber military match rifles.

At some point in the fall of 1882 after the dust had settled, the NRA executive committee approached Col. Bodine with a request that he lead next year’s international military rifle team. Bodine consented.

Bodine had insisted that the defeat of 1882, was one of rifles rather than men. Forest and Stream magazine supported his statement right out across their pages. The paper went further and printed its opinion that “the effort of coaching was effort thrown away.” The English rifle was clearly superior – a blind man could see it. In the winter of 1882-83, the colonel procured a specimen of the English gun, fitted it with Vernier sights and tested it at all the ranges, getting a reference for its average accuracy which was much better than the Remington-Hepburn models. He then tore into the ammunition, the Remington-made .45 caliber, 2.6-inch case length. Independently, he determined the bullets to be much too soft and incompatible with the rifling form. The English bullet was much harder. Bodine substituted tin and antimony-rich bullets for the swaged Remingtons and got much better results.

He made his recommendations for hard bullets, quicker powder, and felt lubricated wads and not what low bid was willing to provide if the U.S. wanted to win a military rifle match. Still not done, he proposed that a dozen of the rifles used by the Englishmen be bought and used in the 1883 matches.

A month later, the same NRA committee read John Bodine’s letter of resignation from the captaincy duties, explaining that his decision was for “reasons which are satisfactory to myself.” Bodine’s comment, somehow and for some reason was reprinted in a Glasgow military newspaper which editorially considered “the Colonel’s apology to the American public for losing the match.”

Bodine meant what he said. The captain of the 1883 team was Col. E.P. Howard. The British leveled the playing field by allowing a team other than themselves to use the wind-gauge sight. The team America sent over for the July 20, 1883, shoot showed some improvement, but still lost.

By 1883, rifle marksmanship in the U.S. was entering a new phase. Creedmoor rifles and the “over-the-hill” back position shooters were now yesterday’s news. The name of Col. John Bodine, “Old Reliable,” once so prevalent on the pages of Forest and Stream, was mentioned just once after that and this a retrospective reference. During this span of years, a neighbor wrote of a grouse hunt, which began by picking up “Capt. Bodine of American rifle team fame” people were reminded, in his wagon for a local hunt.

After being in poor health for more than a year, John Bodine died at the home of his sister-in-law near new Paltz, New York, on June 1, 1904. He was 79 years old. His bride, Ann, had died several years before.

.jpg)

.jpg)