Beeswax As Bullet Lube

feature By: Mike Nesbitt | April, 24

Next, was finding some good beeswax. There is a “Raw Honey” store not too far away from our diggin’s where bricks of beeswax can be purchased and I wanted to get the freshest, purest, and yellowest beeswax to be found. My thinking was that if a buffalo hunter got some beeswax in the 1870s, it would be rather pure and not compounded with other fats, oils or lubes. So, some of this fresh beeswax was purchased.

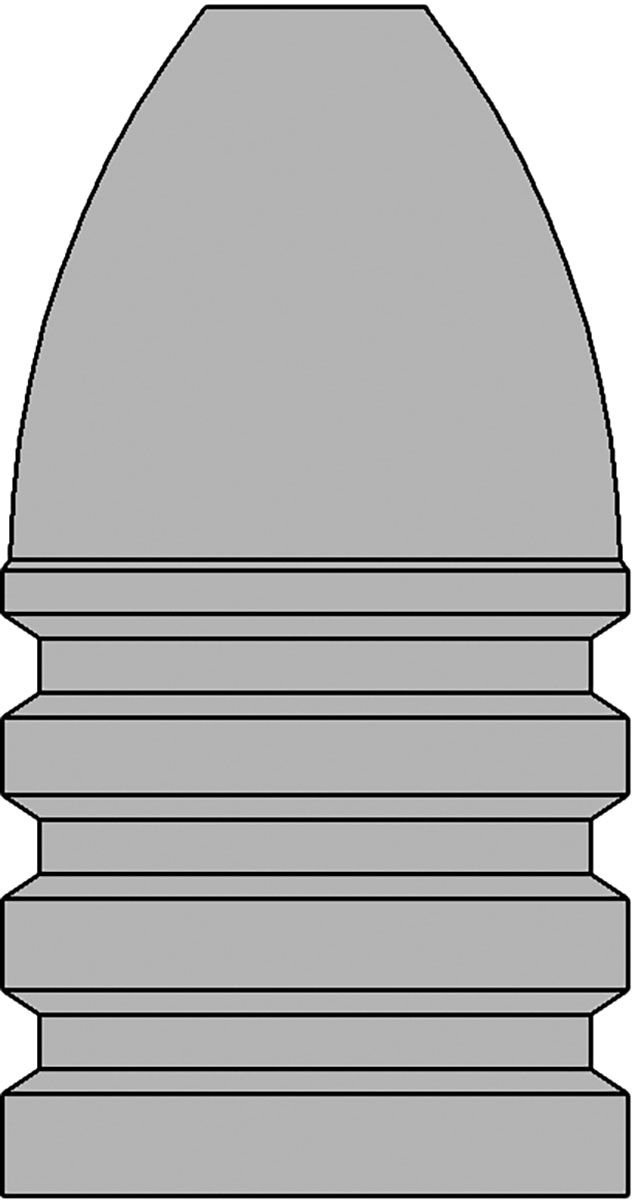

The reason the 50-70 was picked for my first (and maybe last) experiment with the beeswax as a lube was a rather simple one. The bullets for the 50-70 have large lube grooves and that made me think those bullets would give the beeswax the best chance possible. If the beeswax worked well in the 50-70, some could be tried in other calibers later on – that “later on” is still in the future and the 50-70 is the only cartridge being reported on now.

The first load to be assembled and tested used 450-grain bullets from Accurate Molds’ #52-450L2 mould, shot as cast, over 65 grains of Olde Eynsford 1½Fg powder in the Starline cases, compressed under a single .030-inch vegetable wad. Those cases had been fired in my Sharps and they were reloaded un-sized, so the bullets were inserted and seated by hand. Then the loaded cartridges were run through a taper crimp die. To complete the description of the load, they were primed with Federal Standard Large Pistol primers. Those primers were marked with a red X, using a marking pen for load identification and 18 of these were prepared for the first shooting test.

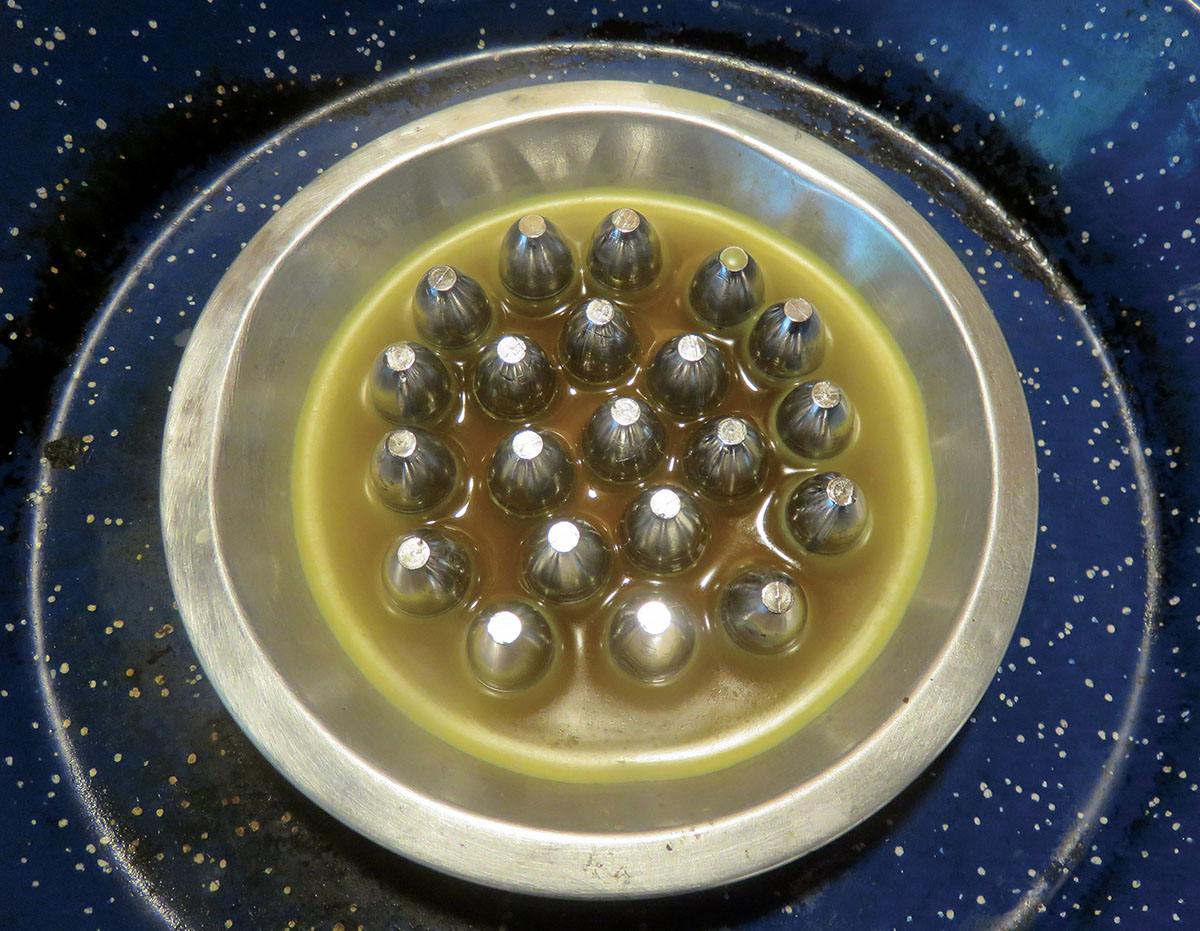

Punching the bullets out of the beeswax “cake” was easy, as long as the beeswax was warm. After the beeswax cooled, it then became difficult to work with. When I put the pie plate back on the heat, I was able to finish getting the bullets out of the cake. At the same time, the cake cutter was also heated by standing it in the beeswax that was melted again. This made punching out the lubricated bullets easy.

Shooting those “greasers” lubed with beeswax came next and I can’t say there is anything outstanding, either positive or negative, about the way they shot. Those loads went off just fine and the bullets all hit the target, which was a bulls-eye at 100 yards. Their group was not the best but that’s probably more from my shooting than any characteristic about the beeswax lube. All of the 18 loads I had prepared, were fired without wiping the bore. Only a blow tube was used between shots. In fact, my last seven shots were all fired at the same target. Those were shots 12 through 18, and all of the bullets were in the black. To me, that seems to be quite reasonable.

However, I wasn’t quite through with shooting grease-groove bullets lubed with beeswax. One more target had to be shot so the group – good or bad – could be photographed. To do this, six more cartridges were loaded with just a slight bit of tweaking involved. The bullets for these six shots were lubed with beeswax, as were the previous load, but this time the lubed bullets were sized to .512 inch before being loaded over 65 grains of Olde Eynsford 1½Fg powder.

My next experiment was to try paper patched bullets with a 1⁄8-inch beeswax “cookie” behind the bullets. This was done using bullets from a Tom Ballard mould, weighing 525 grains and with a diameter of .504 inch. Those bullets were patched with two wraps of 9-pound paper (from Buffalo Arms) and they were loaded over 65 grains of Olde Eynsford 1½Fg powder, compressed under a single .030-inch vegtable wad. Ignition, like the previous loads, was made with Federal’s Standard Large Pistol primers.

This bullet, because of its rather large diameter for a .50 caliber paper patch, needed to be seated rather deeply in the cartridge case. With just over ¼-inch of the paper exposed, these loads chambered easily in a clean barrel although it could be felt when the paper around the bullet entered the leade of the rifling. When the barrel and rifling leade got dirty from firing a shot, those loads wouldn’t chamber, at least not easily. Because of that, even though there was the beeswax lube in the loads, the chamber and bore were wiped, generally with a single moist patch between shots.

The ramrod was put to use again! What I did try however, was to just wipe out the chamber and the rear portion of the bore, leaving most of the barrel un-cleaned but given the attention of a blow tube. For about three shots that worked very well. After that is when my shots began to scatter on the target. Wondering why, I wiped the bore’s entire length and found about four inches of very hard and thick fouling at the rifle’s muzzle. In general, hard fouling near the muzzle is a sign of not enough lube.

More of the paper-patched loads were tried but the amount of beeswax beneath the bullet was simply doubled to a full ¼-inch. Those were fired, at 100 yards again, and even though the loads had the increased lube, the bore was wiped between shots. While wiping the bore, no hard areas of fouling were noticed and the increased lube was working well.

The paper-patched loads did give me the best group of this informal test, although my shooting with the beeswax lubricated loads certainly didn’t break any existing records. Again, one shot did crawl out of the black and that is probably much more my fault that anything I could blame on the beeswax lube.

Further tests and more tweaking the loads could be done. As things stand right now, I’m prepared to give my experiment with beeswax, as a bullet lube, a fairly positive conclusion, based primarily on how it shot when applied to the grease groove bullets. If I use it again with paper-patched bullets, I’ll simply be sure to use enough lube, at least a cookie of 3⁄16-inch in thickness. For grease groove bullets, maybe I should have run them through the sizing die and extruded the lube into the grooves although, at this time, I don’t see how that would make any difference. While I won’t say that beeswax is a really good or a better bullet lube, it is certainly much better than no lube at all.