The Wyoming Schuetzen Union’s “Center Shot”

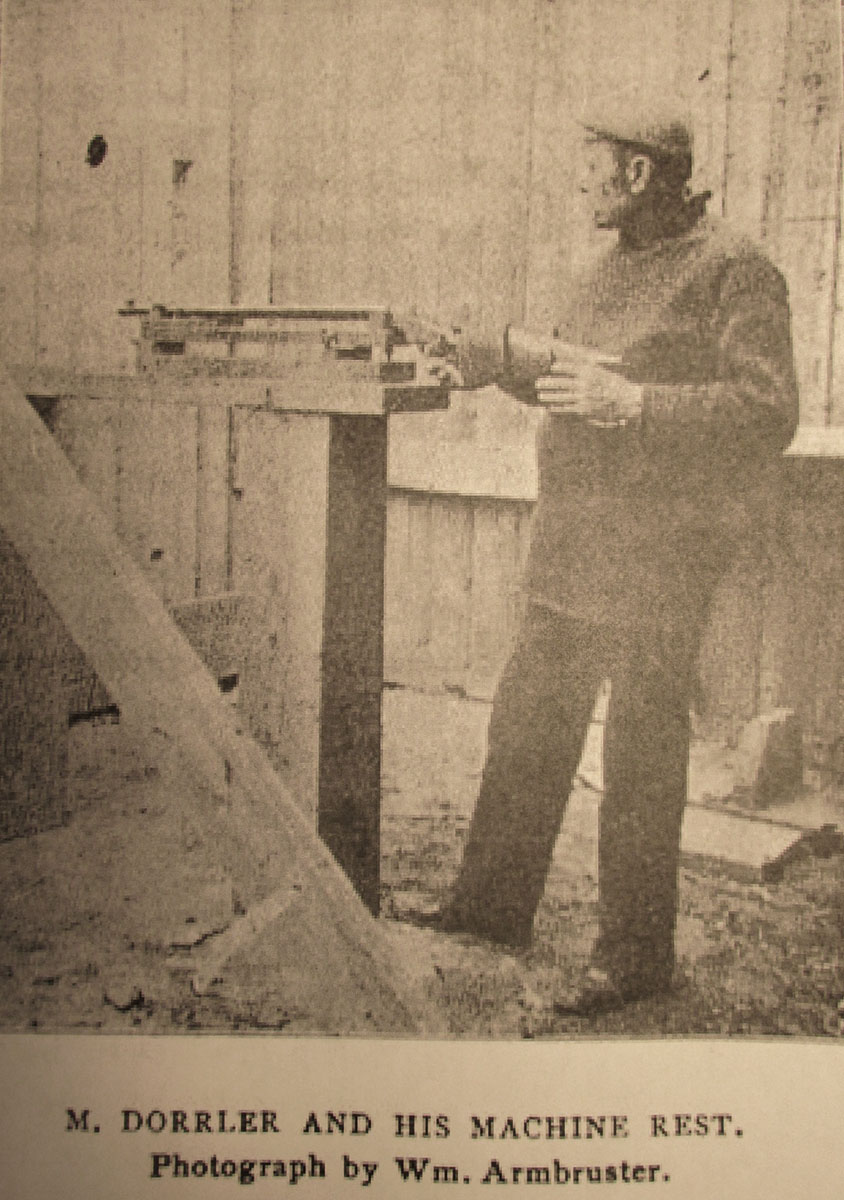

One-on-One with Michael Dorrler

column By: Jim Foral | April, 24

We might expect a less avaricious standard from the era’s serious, yet competitive Schuetzen riflemen that we admire. For some of these, this mercenary factor weighed largely into the decision to take up or throw down the gauntlet to an individual match.

On the other hand, his stimulus may have been for no other reason than purely the wholesome sake of it: for the love of the sport, the chance to compete and to win. These one-on-one matches afforded another chance to shoot and actively participate in the passion that he excelled in. Presenting a sampling of Mr. Dorrler’s matches and opponents may help to shine a light on an unconsidered aspect of the competitive nature and culture of the times.

Regarding Michael Dorrler, this assessment was advanced in 1894 – “In the gallery match he has no equal, and at 200 yards the only man who could get him to lower his colors was William Hayes of Newark. These two have met in several one hundred yard contests with the results on the whole in favor of Hayes.” Hayes, for 30 years a topflight rifleman, was a manufacturing jeweler whose Newark shop fashioned most of the medals and trophies handed out to the winners at many of New England’s shooting contests. His shooting skills brought him a world’s championship in international competition and the reputation as one of America’s top marksmen.

Their best remembered, and most controversial, individual match was the June 26, 1886, classic touted at the time as, “The Ballard against the World.” The 100-shot, 200-yard offhand “hair-trigger rifle” match had been twice postponed, and horrendous winds happened to be blowing on the occasion. The stakes were not of an uncommon type, a dinner for 24 at Del Monico’s. Before a shot was fired, a mutual agreement between the two friends stated that the loser should have the option to stipulate date and place of three additional matches between them.

The Marlin Fire Arms Co., used the match results to make a powerful advertising point by asserting that Dorrler’s actual advantage was that he was “shooting a Ballard rifle.” Moreover, beneficial use was made of the fact that Hayes, who owned three Ballard rifles – didn’t.

As a novel attraction in 1890, both agreed to a 200-shot event, each half to be shot at a different range, for a $100 stake. An impetuously scheduled third match between them evidently didn’t take place. A good percentage of the publicized and promoted individual matches between Mr. Dorrler and his planned opponent failed to receive the expected and awaited press coverage they normally would have. The most likely explanation for this seems to be that one or the other party backed out for reasons not made known, and the match cancelled without public notification. This outcome was a frequent occurrence. The December, 1890, Dorrler vs. Snellen 200-shot gallery match to be shot by halves in New York and Newark is a case in point. Charles Zettler arranged the event and promoted it as one of the most “interesting contests ever shot in America.” Either the publishers didn’t agree with Mr. Zettler’s assessment, or the match didn’t take place. Also, magazine space was limited and it was the privilege of the publisher to adjust content.

L. Vogel, the man well known in Newark shooting circles as “the open sight champion” faced the 200-yard target alongside Mike Dorrler in November of 1884, for a Schuetzen match. When the smoke cleared, Dorrler may have had a case to stake his own claim for Vogel’s title, after handily defeating him 2,017 to 1,837.

Another formidable contemporary that occasionally gave Dorrler a run for his money was John Coppersmith of Newark’s Amateur Club. In 1888, Dorrler belonged to the Greenville Rifle club. On February 20, 1888, he and Coppersmith locked horns in a split 200-shot match for what may have been the unofficial “Championship of New Jersey”. At the second, deciding meeting of the Belvedere House in Greenville, Dorrler came out in front with a score of 1,157 against Coppersmith’s 1,145. Later that year they engaged in another series of one-on-one matches.

George W. Plaisted of Greenville, was skilled enough to occasionally beat Dorrler, as he did by a single point at the Armbruster’s gallery shoot in early January, 1894. Dorrler automatically insisted that his opponent instantly engage him in a man-to-man match, whereupon he prevailed by a single point. The Forest & Stream reporter in attendance, speaking of the many that stayed late, made his stance on the betting well-known: “They had their pocketbooks well lined hoping to turn an honest penny.” Of the few individuals who regularly engaged in the practice of challenging, George Plaisted seemed to be the most prolific. Plaisted relied upon his Ballard 38-55, re-chambered from 38-50, and a 300-grain bullet. He used a charge of 8 grains of nitro powder under 40 grains of black powder. For whatever joy or reward he found in it, the evidence suggests that he made a specialty of individual matches. As an individual consequence during this period, there was a short-lived spurt of matches initiated between other lesser-known shooters that the popular sporting press seemed intent of publishing.

Dorrler and Plaisted weren’t done with one another just yet. In December, 1894, Forest & Stream announced that the two would “hold a little argument” in the form of a 50-shot match at Greenville Park. The excuse they used that time was the good-natured chaffing each experienced about the outcome of their November match, when they finished second and third. The cold, 50-shot, 200-yard shoot off resulted in a Dorrler victory, 1,090 to 1,076.

Mr. Dorrler’s most active involvement in individual matches was in 1894. As the year 1893, wore down, rumors that an impending matchup between the two equally skilled standouts, Michael Dorrler and Fred C. Ross, began to circulate in Eastern shooting circles. Both men were regarded as local celebrities and were avidly followed. The sporting periodicals struck the spark and fanned it into a flame of public interest and anticipation. Forest & Stream publicized the match’s development from scuttlebutt to realization in a style noticeably out of proportion to its customary glossing of a similar event. They made a production of it.

The same issue included the newsy nugget that Mr. Dorrler had shown up at the Greeneville range on New Year’s Day with his new rifle – a 38-55 Ballard match rifle that used a hand-loaded, 225-grain paper patched bullet.

Later that month in the January 20, number of Forest And Stream was found: “Our local riflemen are patiently awaiting the final denouncement in the Dorrler-Ross matter, a match is the only panacea for the highly congested interest in these two experts.” The March 19 issue kept the matter vibrant with the bold heading “Ross and Dorrler Will Shoot” and giving the scheduled date of April 16.

The stakes had been firmed up at a $100 a side. A late March issue contained the reminder that the Ross-Dorrler event would happen on March 31, and did nothing to squelch the public enthusiasm. The Great Ross-Dorrler Match, actually held on April 16, ended as the shooting year’s Great Debacle. The scoring was hopelessly bungled due to the scorers’ general ineptitude and inattentiveness, as well as the misplacement of wet target pasters. That night the scorers and their supervisors gingerly removed each paster and painstakingly numbered and evaluated each bullet hole. They were three hours at the task. In the end, referee William Hayes rendered his ruling that the match was a 2,818-point tie, adding “and all bets are off.” To no effective end the Forest & Stream writer still contributed a “dry as dust” rundown of each 10-shot string of each opponent. On the occasion he couldn’t resist the opportunity to advance his private opinion publicly: “Why not eliminate the element of gambling from our sport? We’d be the better for it.”

The April 16 match at Wissel’s Park had the effect of stirring up rifle matters around greater New York. “The Tie” was the topic of discussion at gun clubs throughout the region for some time thereafter. The second match of the agreed upon “best two out of three” was hurriedly scheduled for April 28 – a two-day notice. The few spectators in attendance noticed that Ross appeared to be in good form, while Dorrler looked “decidedly off”. This time the match staff went to extremes to ensure precise record keeping. Ross shot a 12-pound Schalk-barreled Ballard 32-40, muzzle loading a 160-grain grooved bullet. It was thought that Dorrler used his new Ballard 38-55. When the dust settled, Ross turned in a 2,215, with Dorrler posting a second best 2,184. The Forest & Stream columnist again provided his insipid string-by-string coverage.

Dorrler settled the matter of scheduling the third contracted leg of the Dorrler-Ross series with an odd notification to the Forest And Stream publishing offices, which passed along his decision: “Mr. Dorrler informs us that there will be no further individual matches with Ross. In fact, he says that he retires from all match shooting for the future.” No one that knew Dorrler expected this to last. Indeed, he shifted back on track in a short time. He was caught red-handed on June 2, rifle in hand, at a Hartford Rifle Club match.

The March 16, 1901, number of Shooting and Fishing magazine provided its readers with the particulars of the match between Mr. Dorrler and his fellow Jerseyman Bill Tewes. The two had tangled in a 100-shot contest at Armbruster’s on January 2. Dorrler showed up with his recent acquisition, a 32-40 Stevens-Pope-Ballard that he’d just restocked and reshaped the lever to his idea. Tewes shot his .33-40 Stevens-Pope-Ballard. Both men filled their shells with Kings Semi-Smokeless on top of a smokeless priming charge. It is thought that Kings Powder Company instigated the contest to promote their new powder that was being so aggressively pushed. Tewes was the better shooter that day with 2,204, beating Dorrler’s lack luster score by 53 points.

On February 9, 1904, at Zettler’s Gallery, Bill Tewes scored a 2,460 x 2,500, equaling the record Michael Dorrler had set on May 5, 1901, and before the season was over had bettered that by two points. Mike Dorrler was compelled to pull a tired caper from his worn-out bag of tricks. That May of 1904, a number of Zettler’s members were present when Dorrler and Tewes, along with George Schlicht, met for an impromptu match. Under the circumstances, it seems doubtful that Tewes concocted the plan. The winner remained undecided up to the final two shots. In the end, Dorrler had beaten the man who had beaten his record by three points, and Schlict by seven points. Later that night, Tewes, in a late 10-shot match got the better of the fight and “buried the old veteran” 230 to 208 points. Dorrler and Tewes continued to be back and forth heading the winner’s list for several more years.

“For a small stake” Dorrler faced Walter Hudson in a 50-shot match at Armbruster’s on October 30, 1903. Hudson came out on top by 12 points. A month later the doctor won the annual Election Day Match with a score of 2,301, shattering Dorrler’s 1900 record score of 2,257 on the German Ring Target. It was predicted that Dorrler’s score would stand for many years. Since the Hudson win, Dorrler had been anxious to arrange another meeting, which brings to mind yet another reason to involve oneself in an individual match. Hudson accepted promptly and expressed his hope to better his own record at their next encounter. The grudge match was held under the worst possible rainy conditions on February 22, 1904. The smart money, it seemed, was on Hudson. H.M. Pope and Ideal’s John Barlow were among those in the audience of drenched onlookers. Dorrler showed bad form from the start and effectively lost the match in the first 10 shots. Hudson turned in a 2,239, 52 points ahead of Mr. Dorrler.

On May 2, Dorrler had bounced back and beat Bill Tewes and George Schlicht, “the veteran of countless matches” in a 50-shot match on the Union Hill range. This victory marked the final chapter in Michael Dorrler’s long-term run of individual challenge matches, which had by this time largely gone out of fashion.