The Wyoming Schuetzen Union’s “Center Shot”

Irish Riflemen in America

column By: Jim Foral | April, 24

The headcount of the Irish gathering stopped at 28 individuals, which included the Lord Mayor and Lady Massareen of Dublin, and that city’s Alderman Manning and his daughter, together with a select few of those influential enough to merit inclusion.

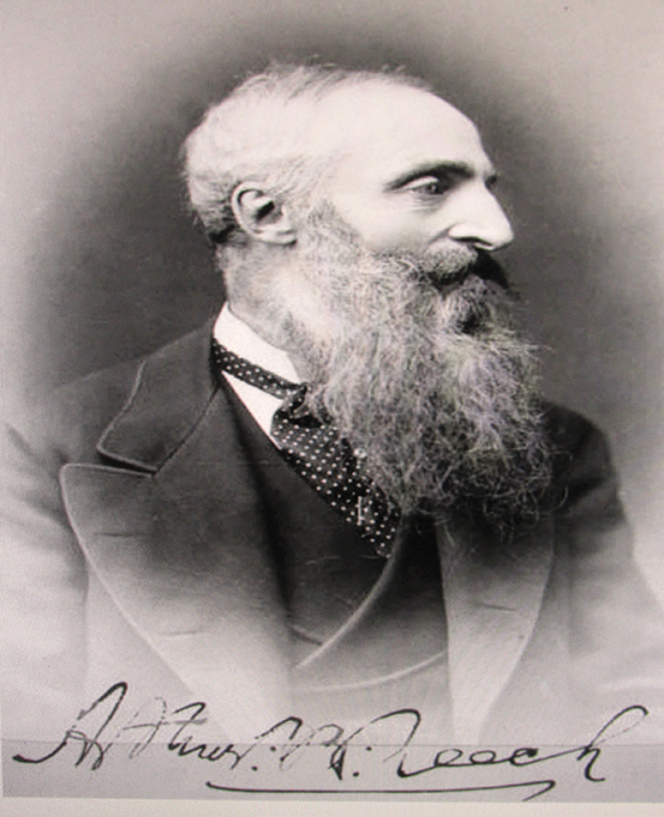

The Irish group was allowed to rest and recover for a day before they were thrown a formal reception banquet in Garden City on Long Island. It was held in the Brooklyn Concert Hall, which was temporarily modified to meet the seating requirements of 300 people on one level. It was on this occasion that the Irish were introduced to the leaders of the National Rifle Association. It was quite the extravagant affair and stately gathering. Major Leech, no stranger to such functions, said that it was the “most elegant and costly I have ever seen.”

All night long, one speech followed another, and one toast lead to a succession of next toasts. During the course of the evening, President Grant, very temporarily in New York City, sent word that he would be delighted to receive the Irish party, but its current commitment and the 20 miles of travel involved precluded accepting the Presidential offer.

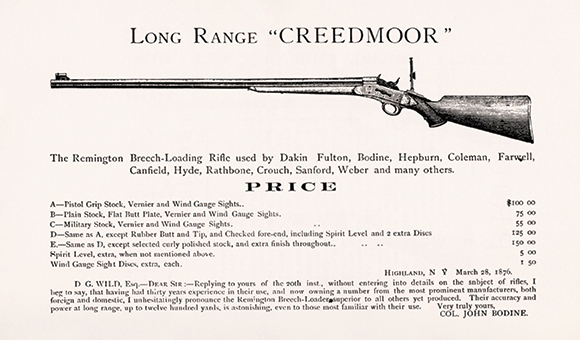

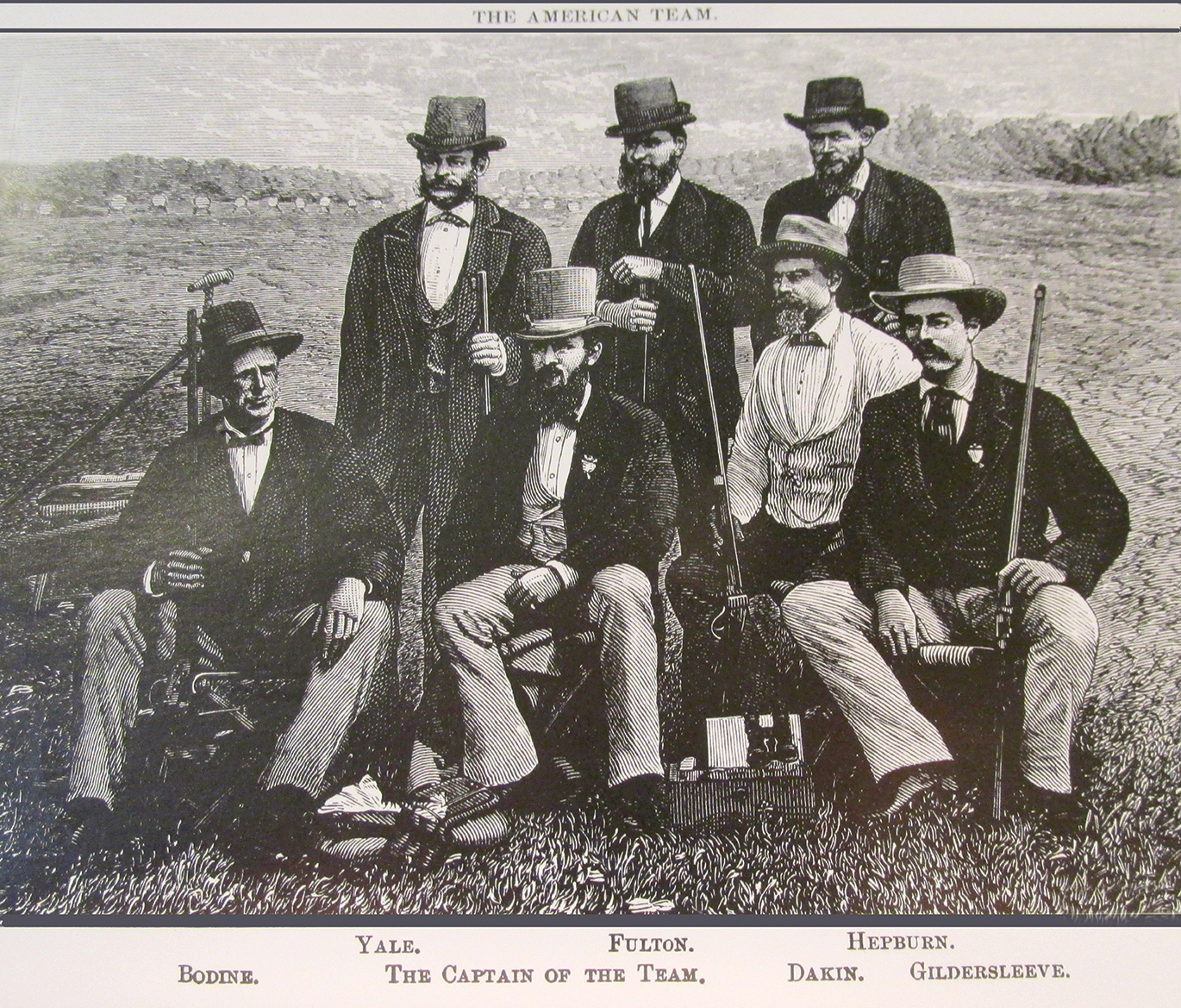

On September 19th, the Irish Team was invited to the Creedmoor Range and was given the opportunity to watch the American team compete in the Remington Diamond Badge Match, and to evaluate their competition. Several of the Irishmen shot the match, as the New York Herald reported, “…for the fun of the thing” with borrowed Remington breech loading Creedmoor rifles on the Rolling Block receiver.

It does seem that members of the visiting Irish party were in demand by prominent businessmen claiming Irish blood coursing through their veins, and they descended upon them almost as soon as they walked off the gangplank. Dinner invitations and outings awaited them. A Mr. Wallack invited the entire arriving party to a day’s sailing on his lavishly appointed 300-ton yacht, the “Columbia”. It happened that the day the “Scotia” was returning to Europe, those aboard the “Columbia” sailed under her bow as a lark.

In the early morning of September 26th, the day of the great match, Major Leech entertained thoughts that he afterwards shared with the readers of his book, Irish Riflemen in America (a title too good to use only once). He expected a close match, he wrote, but was not at all confident of an Irish victory. He went on to reveal not only an aspect of his character, but an aspiration almost certainly not unique to him. Win or lose, he’d hoped that “we had made a step forward towards a friendly hand-grasping with our American cousins.”

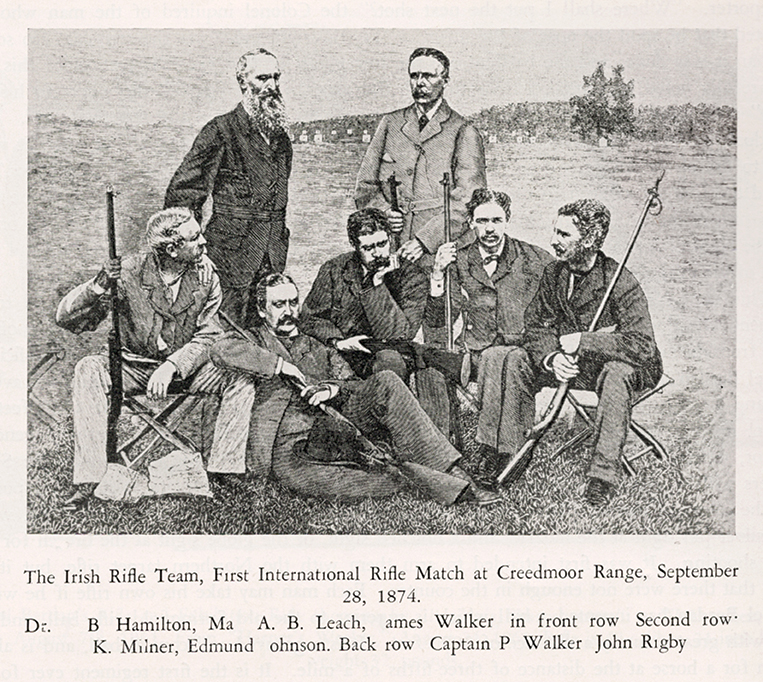

The 800-yard phase took the better part of the morning. The American team led the Irish 326 to 317. The firing had been routine in cadence with no surprises. After lunch, Major Leech delivered a brief speech. On behalf of himself, the team, and the whole of Ireland, Leech thanked the American hosts almost to the point of being overdone. He then made an unexpected presentation of an ornate silver tankard, memorializing the day’s match and the friendship of its competing nations. Col. George Wingate accepted the trophy on behalf of the Amateur Rifle Club and the National Rifle Association. The Leech Cup, as it was thereafter known, was given with the stated intention that it be a trophy for a perpetual long-range match on the regular Creedmoor schedule, as a testament to the friendship between countries in the 1874 contest.

After the crowd finally settled down, there were cheers and back slapping for the Irish and cheers and backslapping for the home team, and medals upon medals all around. It was a grand time to be an American and a grand time and place to be an Irishman.

Leech continued with the sharing of another personal impression. The multitude of spectators gathered at the match, estimated at 8,000 Americans, many of who possessed a considerable percentage of Irish ancestry, were rooting for the visiting team. A throng of human beings of this size, with opposing or uncertain allegiances, could spell trouble anywhere. Still, maintenance of order was left to just six policemen, who never felt challenged

Major Leech had his own sightseeing agenda. He wanted to see more of the central United States and the Missouri Valley in particular. Leech left the party in Chicago and struck out on his own. He visited Saint Louis, south to New Orleans where he spent some time in the company of the New Orleans Rifle Club, at which time they presented him with a lavish gold medal. From there he took a train to Cave City, Kentucky and spent all of the considerable time he wanted exploring Mammoth Cave. After a few days he headed to Louisville, where its Irish citizens gave him a warm reception. Leech toured his way back north, seeing whatever interested him. On November 18th, he boarded the Steamer “Russia”, bound for Europe.

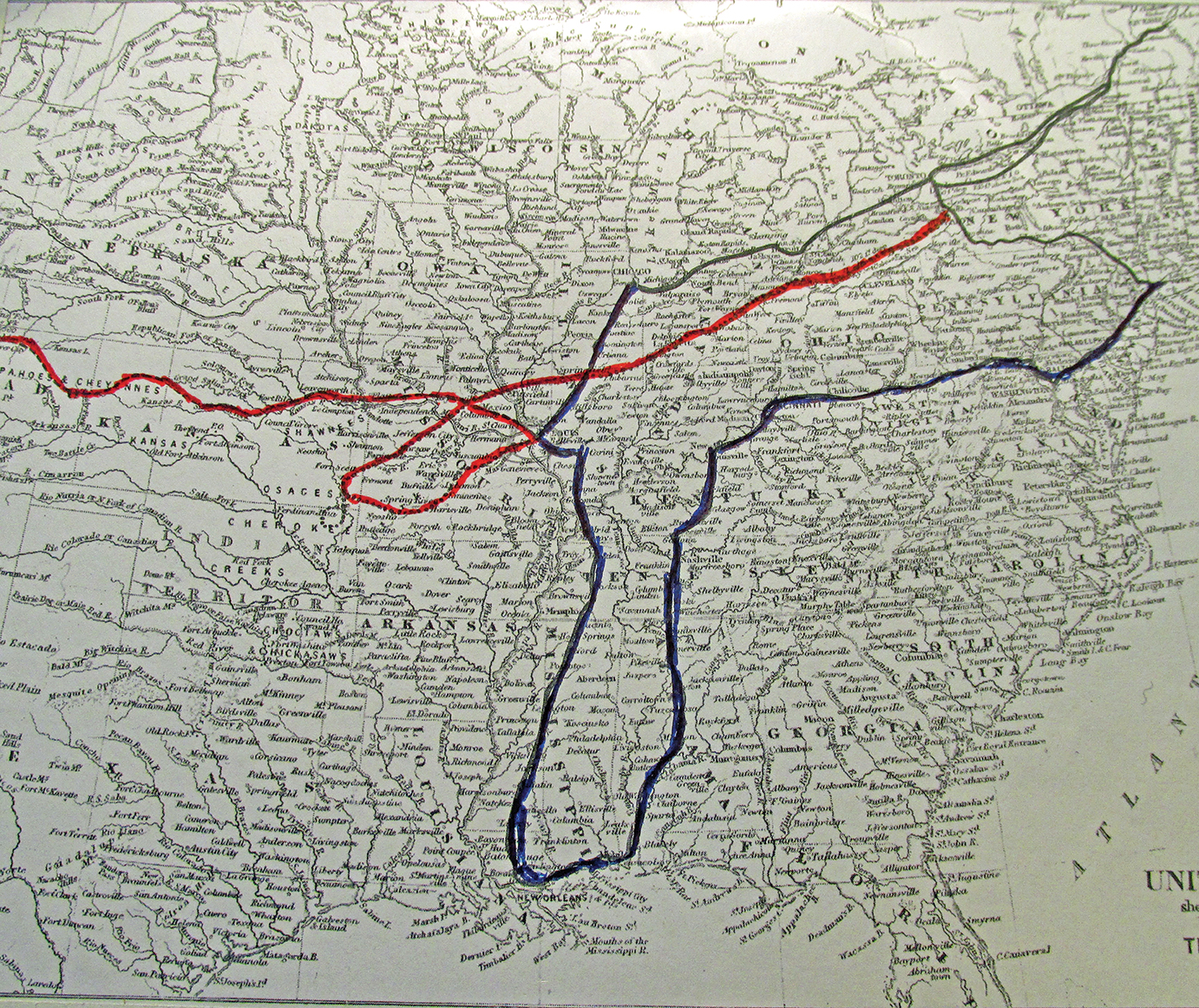

Some of the team members were particularly keen on visiting the western American wilds for a sporting chance at “pinnated grouse”, or prairie chicken. The transplanting of these native American birds to the English countryside by the Prince of Wales had gathered up their Irish enthusiasm.

Charles Hallock, Editor of the popular weekly journal, Forest and Stream, volunteered to arrange an expedition with guides, and secured a 30-day carte blanche passage on the tracks of the Missouri, Kansas, and Texas Railroad. The Irish hunters were five in number. There was John Rigby, Edmund Johnson, J.K. Milner, John Bagnell, and J.J. Kelly.

The officials of a number of railroads coordinated to expedite the hunting party to Hannibal for a tour of indefinite duration. The hunt itself seems to have been ongoing from early in the first week in October until the mid-month when a group of Irishmen were reported returning from a week’s hunt in south-eastern Kansas and the north-eastern part of “I.T.” (Indian Territory), or what is currently Oklahoma. The party accounted for 300 chickens and quail, both of which were particularly abundant. The hunters journeyed overland 20 miles into Indian country and encountered members of the Osage tribe that were both welcoming and friendly, to the extent of loaning them hounds.

It is likely that this same Irish bunch was the one that returned to Hannibal in early November “fresh from the Western Wilds”, with armloads of “deer antlers and other trophies”. Evidence suggests that some members of the Irish rifle team splintered off from the main group. They appear to have ranged further and stayed in the field longer. J.K. Milner returned from the woods in mid-November with reports of “plenty of game” on the plains of Colorado. Milner was pleased to report that he had “killed a few buffalo, deer, antelope, etc.”

With the Irish assembly scattered as they were, with different destinations, schedules, and agendas, they seem to have departed for home independently. The objectives of the hunting party changed in time and they separated and scattered. Some went to Denver, some to Chicago, and others back to New York. There is no public notice of the Irish boarding a Dublin-bound steamer as a group, as they had arrived, suggesting that they left singly or in small groups that attracted no special attention.

Major Leech, who sailed for Europe on November 18th, wrote on the 15th, that “my friends who accompanied me to America, where we arrived on September 16th, have returned to Europe, but I myself will sail in a day or two.”

The 1874 Irish visit was such an extraordinarily positive experience to have emerged from a competitive sporting encounter. The meeting put a reciprocal man’s humanity to fellow man’s stance at the forefront and on full public display. In early November of that year, NRA president Col. William C. Church summarized the fervent mutual desire: “Now that the greater portion of the Celts have returned home, we wish them unbounded happiness through life, and hope that when next the visit us, they may know nothing worse than the hospitality with which they have received on their first visit.”